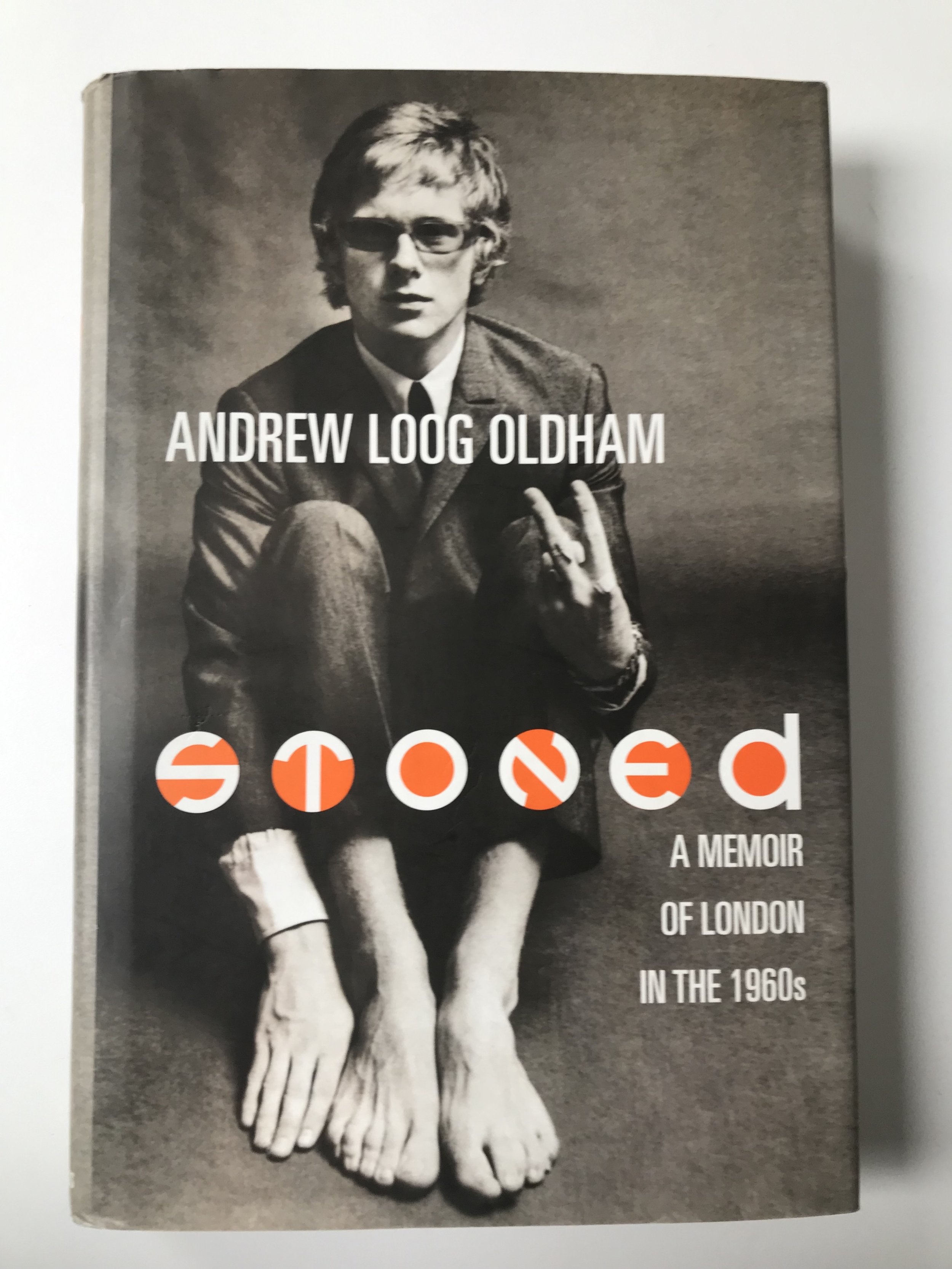

Nik Cohn has published only a handful of short stories, ‘Mad Mister Mo’ from the October 1966 edition of King magazine is therefore something of a curiosity piece .

Given that his father was a celebrated history professor I guess you could chance a Freudian reading of this story of Mad Mo the history teacher: ‘He smelled of chalk all over and wore a ragged black gown with holes in it. When he walked, he gathered his black gown in tight around him like a shroud’. He is a monstrous figure who ‘threw out his arms like a mad messiah and he preached me lust and thieving and blashemy. He shouted at me and he said that religion was bad and murder good, love was bad and hate was right’. He preached me the triumphant victories of evil’.

Mo is certainly mad, but is he a tyrant, drunken fool or phantom figure of a child’s imagination?

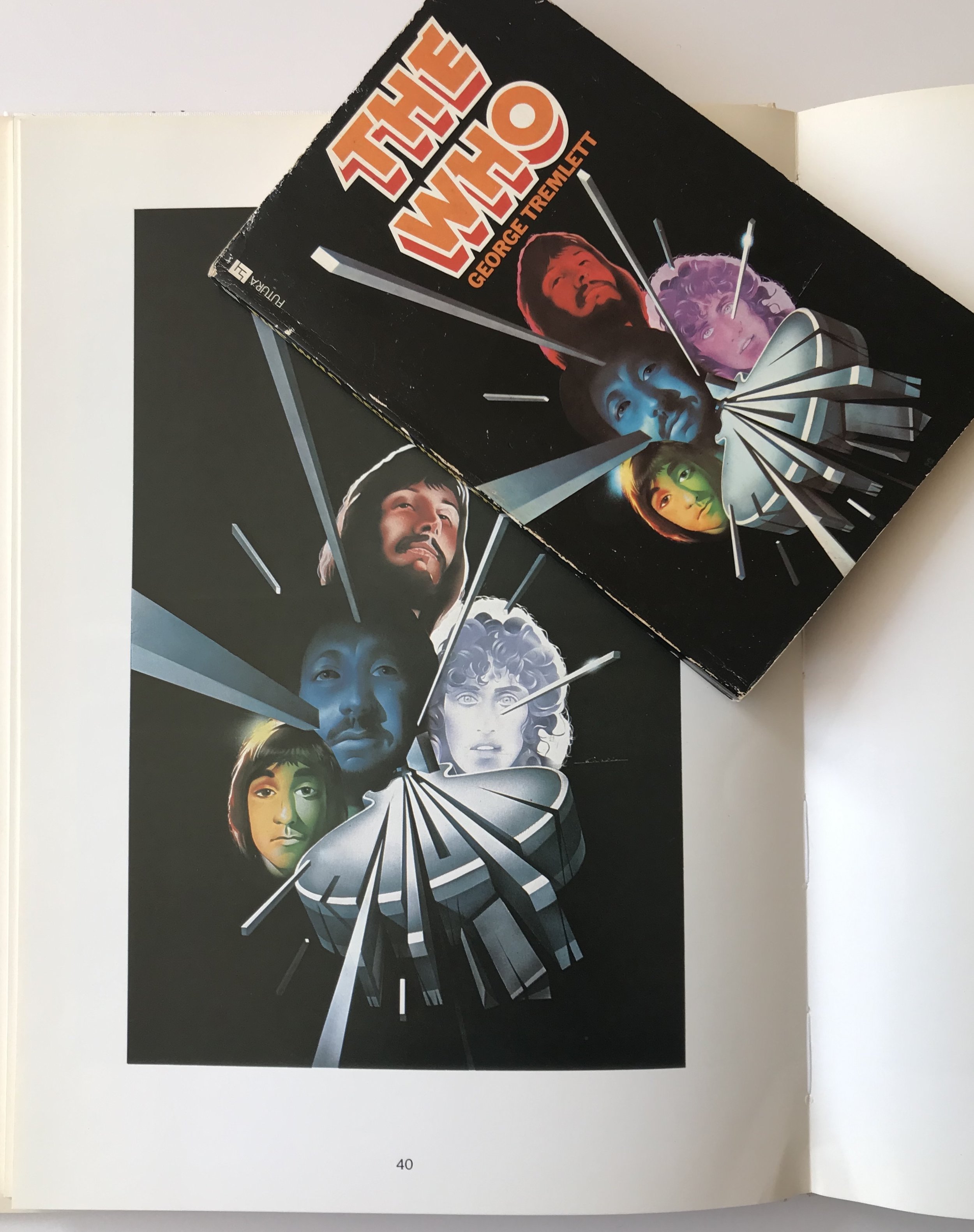

Illustration by Peter Adkins

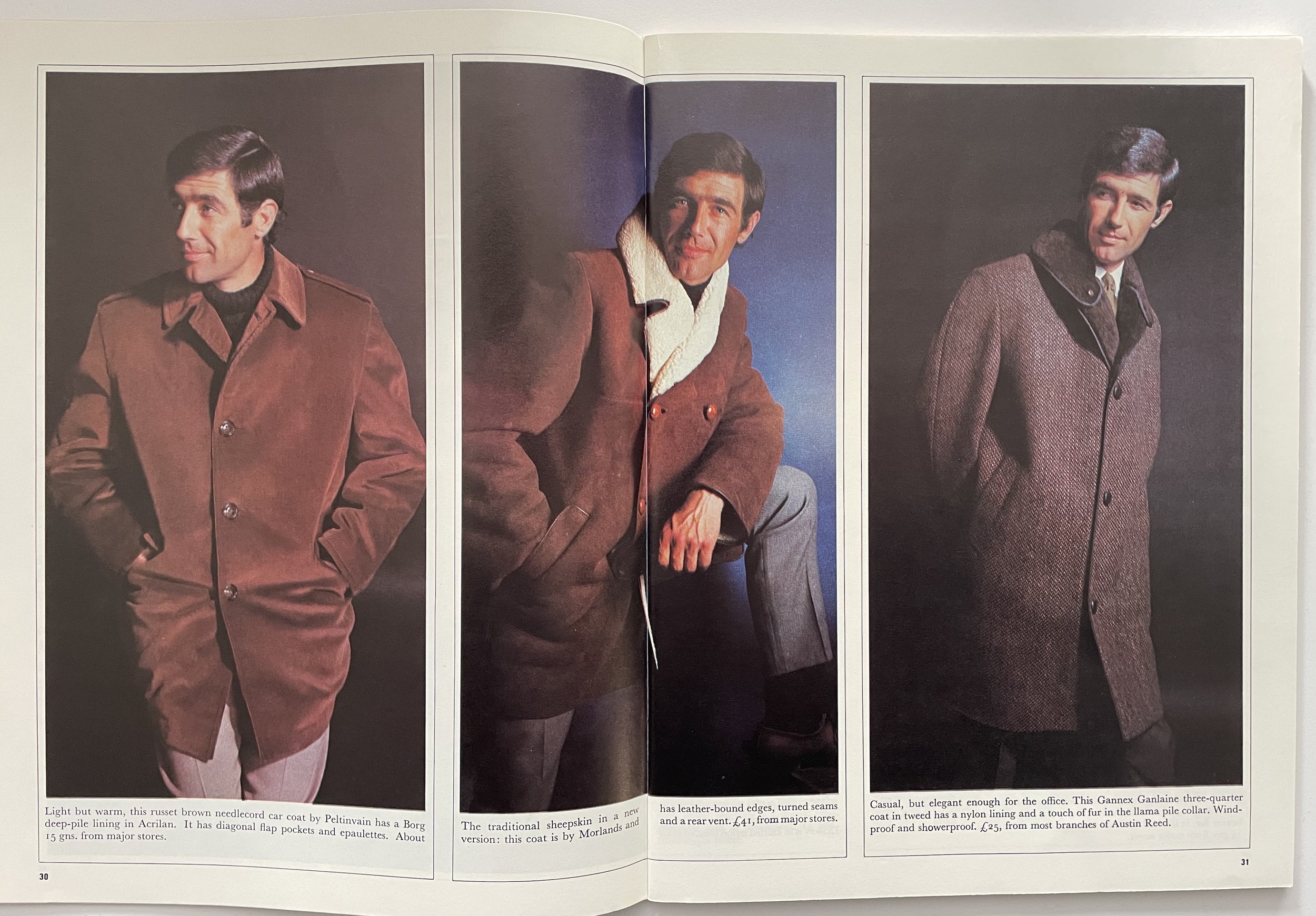

King was a fairly high-end men’s magazine, backed initially by Paul Raymond. It ran from 1964–68 when it was subsumed by Mayfair. I like to think its ideal reader found his surrogate in this male model puting some shape into the latest line in car coats – the well groomed man . . .

This issue also featured a piece and photograph by the great Val Wilmer on Thelonious Monk

Following on the heels of Cohn’s story is a report on drugs and Oxford, there’s no writer’s credit, but I imagine whoever penned this piece had some first-hand knowledge of both Oxford and the scene even if the tone is sensationalist.

The image of the student in mortor board and gown transforming into a bird imprinted on a sugar cube is rather wonderful, blocked and trippy even

What really catches the eye is the description of the dealer working the room with a Bob Dylan record under his arm:

The boy in the combat jacket with a face like the lead singer of the Yardbirds, but with a different intention has found a customer. In the airless bedroom, among the socks, he carefully unrolls a cigarette, watched by the young and eager faces of his new-found friends, and spills the tobacco on to the back of his Bob Dylan record.

The Pusher Men of Oxford . . . but ‘with a different intention’. Rave (May 1966)