The True Story of Arfur the Teenage Pinball Queen

Autumn 1974 and the publicity machine for Ken Russell’s soon-to-be-released film of Tommy was in full throttle. To attract the patronage of those not familiar with The Who’s masterwork, the director and the band courted the mainstream media, which was why Pete Townshend, posing behind a Williams pinball machine, was the cover star of a November edition of the BBC’s listing magazine, Radio Times. Inside he and Roger Daltrey are interviewed along with illustrator Mike McInnerney and journalist Nik Cohn, for whom Townshend said he wrote ‘Pinball Wizard’: ‘I like Nik’s ideas, he’s always made me think.

I used to play a fantastic amount of pinball. Sometimes I played pinball with Nik and Arfur (the little American pinball Queen) . . . Why pinball instead of snooker? When it comes down to it there are so few games of basic skill that you can play where there is a minimum amount of eye involvement. It helps to see and it helps to hear but you can get incredible scores just from letting the ball do what it wants to do. I couldn’t imagine Tommy groping a Go board.

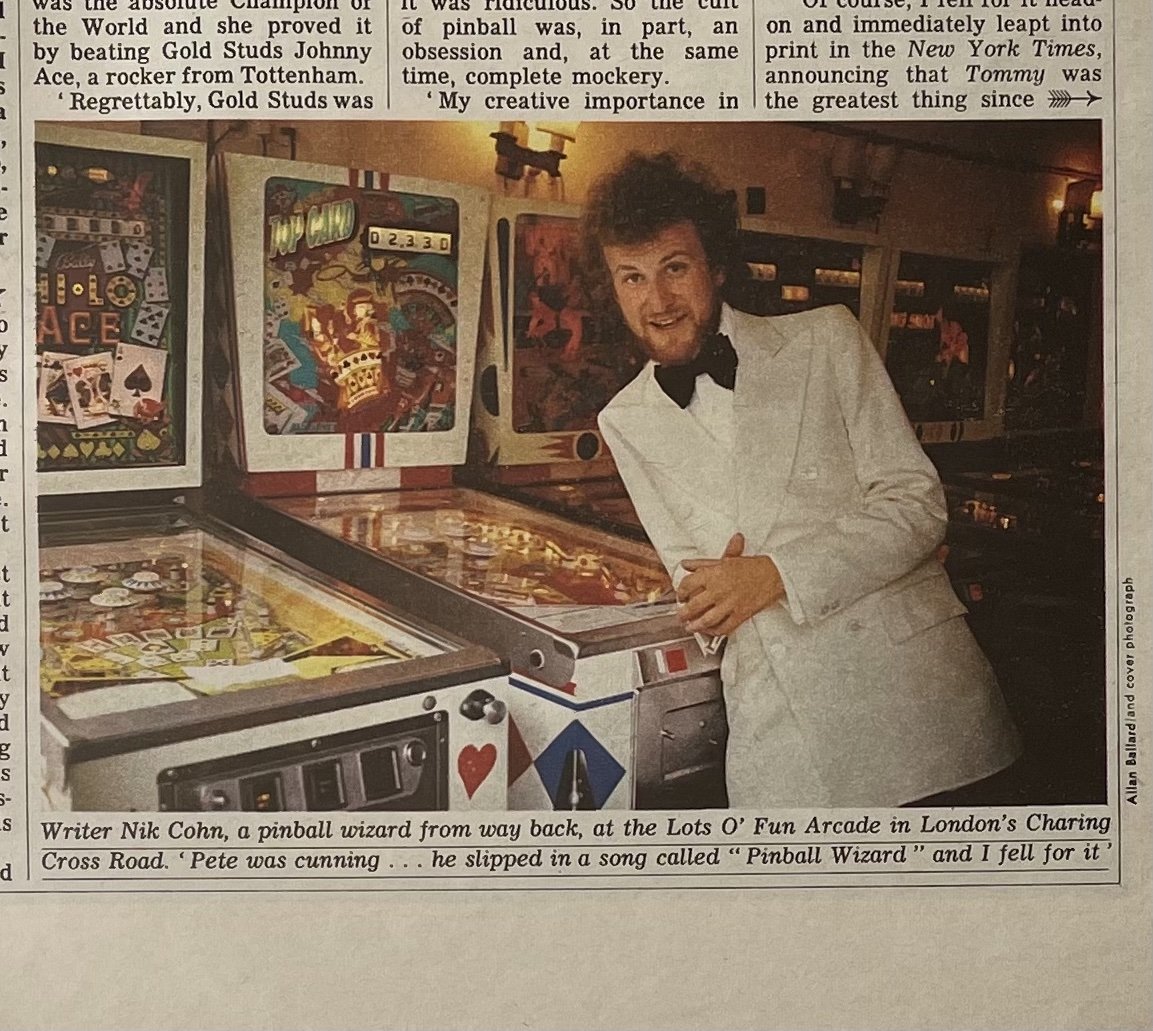

‘Ten years ago, I used to play pinball’, Cohn told the Radio Times, ‘I played it every night and it was the greatest passion of my life. I went to the Lots-O-Fun Arcade in Charing Cross Road and played Gottlieb’s soccer from opening to closing time. Pinball was the only thing that made me care at all.’ Townshend could better him and even Kit Lambert had his measure, ‘In the end I had to substitute a kind of alter ego, who was Arfur. She was 14 years-old and I promoted her as the greatest pinball artist the world had ever known. She lived clean, she thought clean, she shot clean pinball. She was the absolute Champion of the World and she proved it by beating Gold Studs Johnny Ace, a rocker from Tottenham. Regrettably, Gold Studs was very dirty in the mouth, so he had to be deaf and dumb. As far as I know, that was the embryo of Tommy.’

For Cohn, pinball was an ‘echo of capital-P Pop.’ You embraced it passionately or not at all, it was addictive, ‘new and glittering’ and it was ridiculous; a cult, an obsession and ‘at the same time, complete mockery’. Counter to what Townshend had told the reporter, Cohn said he had no creative input into Tommy, he hadn’t heard the album until it was finished and ‘Pinball Wizard’ was only included to play to his vanity and ensure a good review for the album in the New York Times, which duly followed. Some of this was true, some was myth, which was equally true.

David Wills illustration for Let It Rock (January 1973). The ghost of Gold Studs Johnny Ace can be seen at the pin tables

Cohn’s review of ‘The Who’s Pinball Opera’ called the album ‘possibly the most important work that anyone has yet done in rock’ and, not surprisingly, he thought that the ‘use of the pinball machine as the central symbol is a good original touch’. In his autobiography, Townshend recalled he had become friends with the writer, who was part of Lambert and Stamp’s social circle, and they had taken to hanging out and playing pinball together in the arcades in Old Compton Street, near Track’s offices. Cohn was then writing his novel Arfur: Teenage Pinball Queen. Townshend recalled:

One day Nik brought Arfur – the real girl who was his inspiration – to meet me. She was short, with short dark hair, pretty and rough-cut in a tight-fitting denim jacket. We would play pinball furiously and competitively and she slayed me on a machine with six sets of flippers. After our games Nik and I usually popped over to Wheeler’s oyster bar for lunch. We were terribly Sixties pop about this – pinball, oysters and house Chablis.

According to Townshend, Cohn thought Tommy in draft form was ‘pretty good. But the story was a bit po-faced and humourless.’ ‘Pinball Wizard’ was Townshend’s answer, his attempt to provide a little levity, and Tommy, Cohn and Arfur all play a ‘clean’ game.

Cohn’s novel was published in March 1970 to little fanfare, 10 months after Tommy was released. The Sunday Times called it ‘a jolly little piece of inventive nostalgia’, that was ‘full of rich B-feature nomenclature, Runyonesque detail and sheer high spirits.’ It was all about, the critic noted, ‘the pursuit of style.’ The Financial Times’ reviewer thought the whole tale highly colourful and asked whether a book could be psychedelic? And if it could, what was its message? Because what is ‘Arfur’s future, all passion spent, at 16?’ None of the broadsheet reviews of the book mentioned either Tommy or The Who. In the underground publication Friends, Jonathon Green readily picked up on the connection and called the novel ‘Tommy in drag’. But most reviewers were either unaware of the association or made little of it. Arfur was published in the States in May 1971, 14 months after its British debut. Sales there and elsewhere were unimpressive and the novel only made it into paperback in Britain and then not until September 1973.

Regardless of Arfur’s commercial and critical invisibility in the shadow of Tommy, the novel’s titular character had achieved a public profile eight months before the album’s release. Arfur had been the cover star of an October 1968 edition of Queen in which she was promoted as a real life pinball celebrity. The magazine almost always featured an upcoming female film star or model of some renown on its cover, usually just a head and shoulders shot. The October edition was an anomaly with an unknown Arfur posed sitting cross-legged, dressed in black pants and lace-up shoes, a blue and yellow striped knit top and red braces. On her head she wore a fedora. Inside she briefly expounds on her career and philosophy: ‘Live clean. Think clean. Shoot clean pinball.’ Cohn had been the magazine’s pop columnist from 1966 to 1968 and obviously knew how to hustle the editor. The cover photograph by Ray Rathborne was used on the dust jacket of the novel with another, on the back of the cover, of Arfur playing pinball alongside a punkish looking Cohn in sunglasses and a leather biker jacket.

The story in Queen had been preceded in London’s Evening Standard (August 31, 1968). Ray Connolly described Cohn as a ‘writer, rocker, hustler’ and here was the hustle . . . which included Kit Lambert cutting a record with her – ‘The Story of Arfur Pinball Teenage Queen’

The novel’s apparent overlap with Townshend’s Tommy is striking, suggestive of shared fantasy worlds built around pinball tables, yet the similarities are mostly superficial. The key difference between the two pinball wizards, Tommy and Arfur, was that the latter was all myth and style and the former all metaphor and spirituality. Tommy operated on a higher plane, Arfur found her sense of self in the romance of a demimonde. Arfur has yet to escape her mythical status; Tommy, on the other hand, became a pop legend – eclipsing even The Who and Townshend, his creators. In the Radio Times, Cohn recalled his time spent touring with The Who in America where Tommy had ‘become a full-scale religion. When “See Me, Feel Me” sequence came on, the entire audience would leap to its feet and go into instant frothings. What was so depressing was that the next night they would froth for Jesus Christ Superstar’.

In contrast to Tommy’s messiah figure, Arfur is an Alice in Wonderland for the pop age. In the novel, her story proper begins when she falls through a funfair mirror and ends up in Moriarty – a kaleidoscopic amalgam of Sax Rohmer’s Chinatown, Conan Doyle’s Limehouse, Jelly Roll Morton’s Storyville, and Sergio Leone’s Wild West. A world of bar rooms, opium dens, brothels and gambling parlours, peopled by characters drawn from literary history who include Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Jack Kerouac’s Dr Sax, Lewis Carroll’s Alice (here gin-addled and consumptive) and figures celebrated in old-time songs and stomps; honky tonk bullies who take after Stagger Lee.

It is a picaresque tale in which Arfur wanders aimlessly through Moriarty’s tenderloin and its subterranean labyrinths. She is helped on her way by kindly gentlemen such as the Chinaman Lim Fan and the operator Otto Schultz – a professional tear jerker – while mingling with the underworld’s denizen’s – Sun Ra, the process preacher; Skinny Head Pete, Chicken Dick and the Pensacola Kid; Chinee Morris, who left two hundred suits at his death; Jack the Bear, a heavy so tough he could chew pig-iron and spit razor blades; and Willie the Pleaser, a card sharp whose only purpose in life was to ‘live with style’.

The story follows Arfur from 11 to 16 years of age – as her name suggests, and in keeping with the porous boundaries of the world she inhabits and the blurring of first and third person narrator – she is of uncertain gender. Midway through the novel she discovers pinball and acquires an attitude and style that is to be envied. During an intermission in her story, Cohn describes the game, something of its history, and its attraction:

Pinball offers pure sensation: it looks perfect and sounds perfect and feels perfect, it has lights that flash and bumpers that buzz and numbers that unspool endlessly, it is speed and it is stillness, it is turmoil and calm, it is anything that the player cares to make of it. And always there is this, a certain secret connection, him and it, the player and his machine, and a time arrives when it isn’t possible for the player to miss, when he is one and the table and he understands everything.

The allure of pinball is like rock ’n’ roll’s; flash living in a world of extremes – pure sensation – where the game is to become the complete stylist – immaculate, clean and sharp – to master movement and to channel noise and light, to morph, from street punk to the ultimate pepped-up Modernist; machine styled and streamlined with neon light reflected in a chrome finish.

If Tommy was an idea, a physical manifestation of a spiritual world, Arfur was a fictional character Cohn and Townshend turned into a real person, that’s if you believed the stories they told of her exploits. The photographs in Queen suggest Arfur was real enough, but perhaps she was just an actor hired from central casting? Townshend once described her as a prostitute, or at least said he thought she might be. If she was a living person, who did play pinball, how did Cohn figure in her story? Perhaps she was just his muse? Was he her Svengali? Or was he using her to become the world’s first pinball impresario, an Andrew Loog Oldham or Tony Seconda of the electronic table?

Back in February 1969, in an edition of the Eye, a short-lived Hearst magazine aimed at the discerning teenage girl, Cohn had introduced his pinball protégé to American readers. The three page article was illustrated with photographs of the same girl who had appeared on the cover of Queen three months earlier. 15 years-old, 5 feet 2 inches tall and she weighing 95lbs . . . ‘the greatest pinball artist of our time’. Cohn said he first made her acquaintance when playing the tables in the Golden Goose in Soho, ‘Mister’, she said, ‘you shoot nice’. They play and she smashes him. She tells her story, born in Montreal, an orphan since the age of six, a lost soul until she discovered pinball at age 12 when she quit school and moved into the arcades. When her aunt came to take her home she ran away, first to New York, where she became a pinball hustler and made her name, and then, hearing that there was good pickings in Europe, to London. Her legend grew. Before long she had met the Stamp brothers, Terence and Chris and the latter’s partner Kit Lambert, and they ‘flipped for her’ and signed her to their label. Cohn became her manager, Arthur Brown ran her fan club and she appeared on the cover of Queen. Bill Wyman had written her a ‘highly commercial song’, Cohn added, and Lambert had booked studio time. But as Arfur said, ‘That’s all bull – I’m a pinball artist, what else do I need?’

The following month, Arfur was featured in Canada’s Windsor Star Weekend Magazine, still thinking clean, living clean and shooting clean pinball, though she was now said to be a 16 years-old and the product of Montreal’s slums. The photographs didn’t lie, it was the same girl, still sporting the Fedora and braces, but something had slipped and it was not just her age. Arfur, the paper revealed, was actually Pamela Marchant the daughter of rich Westmount parents. ‘Arfur are you for real?’, it asked.Her upbringing was that of any suburban middle-class girl, albeit one with an overly creative imagination, said her school friends. Her introduction into London society had come about when she visited England to stay with her older sister, through her she met Terence Stamp ‘and a writer who wanted her to assume the role of a character he’s created’. When Pamela wrote back to her friends at home she now signed her letters from ‘Arfur’ and her game playing was fearless:

Shooting one or two balls, I can tell how long it is going to take . . . The pinball table is a fine, delicate instrument, and it has its own rights. I never play against the table; I play with it against my opponent. There is a oneness, a life force, and that’s why I cannot be beaten. . . she doesn’t think, she is. ‘Every flip’, says Arfur, ‘has a purpose. I feel where the ball is going.’

The best pinball tables are made in Chicago by the Gottlieb company, but Arfur’s favourite is the William’s Apollo. ‘It’s a clean table, a machine with a lot of soul and a terrific sense of logic.’ Townshend also preferred that table, he had told the Radio Times: ‘While on an ordinary machine you could score 1,000, on the [Apollo] you could score a million. The bloke next to you was scoring thousands and you were into the millions and trillions and he really thought you’d achieved those scores.’ Apollo or Gottlieb, whether it scores in tens or hundreds, to play the game you have to think clean, live clean and shoot clean. The rest is just storytelling.

Years later, only faint traces of Arfur’s story can be found on-line; digital scuttlebutt suggest she returned to Canada, played a supporting role in a Montreal underground film, and then moved to New York where, so it is rumoured, she married Nik Cohn. Sometime around 1974 she simply vanishes from the record.

Pamela Marchant in Montreal Main (Frank Vitale, 1974)

Coda: Arfur, the Ghost of a Myth

Inspired by the hoo-hah over Clifford Irving’s hoax Howard Hughes autobiography (for which he was sent to jail six months earlier), Nik Cohn detailed his own dabbling in the dark art of the pop phenomena, inventing sensation out of nothing, for Harpers & Queen (January, 1973). Or was it because he had seen Arfur’s ghost?

His own attempts at the big hoax, he wrote, had included Eddie Malchance, the Suicide King, Sailor Jones, the Trucker with a Difference and Sinus Schwartz, the kid with the Golden Nose. None had proved successful, but he had come closest to the jackpot with Arfur, the Teenage Pinball Queen.

He retells her story, adding little details, like her modelling of see-through blouses, appearing on ITN news when she scored a quadruple replay and her undertaking a nationwide tour, but Cohn’s big reveal is the fact that she couldn’t play. Despite all the hype (’68 was a tawdry year) no one was fooled, she returned to America from whence she came and rumour has it became a nun.

That was not the end of things. Sometimes the narrative cannot be controlled and, as time passed, she became a legend, her story became fact and then turned into a haunting for her inventor.