The Who

Art/Pop: Side Two of Ready Steady Who

The Ready Steady Who EP was released early in November 1966, on the same day as the last of Shel Talmy’s attempts to milk whatever My Generation still had to offer with ‘La-la-La Lies’ b/w ‘The Good’s Gone’. Penny Valentine’s singles review column in Disc and Music Echo suggested that these Who releases represented some kind of ‘mini-bonanza’, which was certainly true when you factor in ‘I’m A Boy’ b/w ‘In The City’, released only eight weeks before the EP, which in turn preceded by just four weeks ‘Happy Jack’ b/w ‘I’ve Been Away’ and A Quick One album.

After listing the three tracks on Side Two of the EP, Penny Valentine called ‘Disguises’ ‘funny (or was it my record player)’ and ‘Circles’ ‘great’ though ‘mysteriously flat-sounding which is its appeal’. The contrast between the musical identities displayed on the top and bottom deck of the EP was indicative of a kind of schizophrenia that involved a simultaneous race into psychedelia and a retreat into pop formula that the band embodied as 1966 evolved into 1967.

For a group who were never particularly prolific, all this release activity did indeed represent an unusual level of productivity. The yield was finagled, however, by an over reliance on cover versions and previously available tracks. On its top side, Ready Steady Who contained only one new Townshend composition, ‘Disguises’, which was coupled with a rerun of the withdrawn b-side of ‘Substitute’, ‘Circles’. On the underside there were three ready-to-order versions of ‘Batman’, ‘Bucket T’ and ‘Barbara Ann’. Ostensibly, the EP was intended to link with The Who’s 16 minute Ready, Steady, Go! showpiece that featured alternative versions of a number of the EP tracks. The programme first aired on October 1, meaning there was a lag of at least 4 weeks been broadcast and record release.

The French EP which dispensed with the ‘unnecessary’ Townshend originals and added ‘Heatwave’ for maximum effect

Even more tardy with their release schedule had been New York’s The Regents. They had recorded ‘Barbara Ann’ in 1958, when it sounded precisely of its moment, but kept it in the can until early in 1961. Even if a little stylistically dated on its release it still carried enough novelty appeal to enter the Billboard Hot 100 in the Spring; the same week that Del Shannon’s ‘Runaway’ was number one and Ernie K. Doe’s ‘Mother-in-Law’ was number two. In the week Ricky Nelson’s ‘Travelin’ Man’ held the top spot, ‘Barbara Ann’ reached its peak at number 13. Thereafter, it remained a lucrative copyright with significant cover versions by Jan and Dean in 1962 and The Beach Boys in 1965, who took the song back into the charts.

When The Regents ‘Barbara Ann’ was issued in the UK by Columbia in June 1961, Jack Good, television’s hep producer of youth programmes, used it in his Disc column to call out the vogue for ‘copy-cat’ records. He considered the band to be a ‘watered down version of the R&B vocal group The Marcels’. It was a fair critique if you allow for the fact that The Regents track was recorded two to three years before the Marcels’ debut disc, ‘Blue Moon’. But Good’s point carried a certain truth; ‘Barbara Ann’ was indisputably derivative of black vocal group styles. In the following edition of Disc, hosting the paper’s weekly Disc Date, Don Nicholl showed no interest in the provenance and authenticity of ‘Barbara Ann’. He simply wrote that the ‘A BA-BA-BA-BA rocker’ was ‘sung by male vocal group . . . High-pitched lead voice above the deep chanting of the others’ and was ‘good juke material’. That too was true.

Subsequent covers hewed close to The Regents’ template, making only small modifications in the arrangement. Giving themselves the space to add even more ba-ba-ba’s, the Beach Boys’s 45 discarded the saxophone solo prominent in the two earlier versions. The Who did the same, but noted its absence by replacing it with some Goon-ish whistling. The whistle sat on top of Townshend’s discordant guitar fills (a continent and an ocean removed from a surf-styled vibrato twang). When Jan and Dean produced their version, the song still had some contemporary currency, being released only a year earlier, the original had not yet faded from the collective pop memory. But when the Beach Boys cut their copy, four years on from The Regents, it qualified as a certified oldie and was delivered as such. The Who’s ‘Barbara Ann’ was something else again; at once a homage and a piss-take.

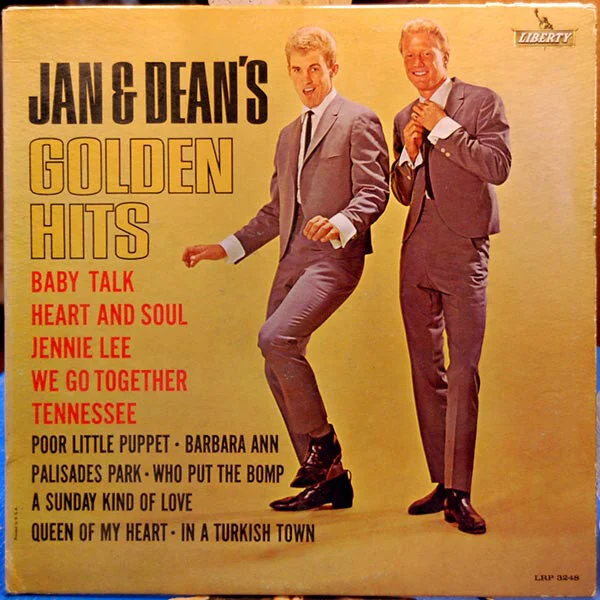

In need of material to fatten out a hits collection, with a title untroubled by the truth, Jan and Dean recorded ‘Barbara Ann’ for their Golden Hits. At that point, the duo were still over a year away from getting their boards wet with ‘Surf City’, which was followed by a run of genuine chart smashes sufficient enough to stuff a hits package to bursting without any padding. In 1965, three years on, the pair were cutting tracks at Western Recorders at the same time as the Beach Boys, in an adjacent studio, were pulling together their Party! album. That LP, like Jan and Dean’s was a record required to keep new product before the public; a necessity as Brian Wilson toiled away on Pet Sounds.

The musically creative half of the duo, Jan Berry, like Brian Wilson in the Beach Boys, was trying to push the envelope of pop beyond formula and the superfluous. Berry’s big opus was ‘A Beginning From an End’, which Joel Selvin in Hollywood Eden: Electric Guitars, Fast cars, and the Myth of the California Paradise describes as a ‘turgid potboiler of a song about a man whose wife dies during childbirth and who is reminded of the dead woman by their daughter’. Jan had laid down the complex instrumental tracks and was attempting to pull together the vocal arrangements, but Dean had had enough of the maudlin affair and walked out.

Down the corridor he joined the Beach Boys who were working on their sing-a-long album that interspersed, between covers of rock ’n’ roll favourites, bits of playful banter and a wholesome party atmosphere. Alongside a medley of their own hits were three Beatles numbers and a Dylan tune. These were joined by older familiars ‘Hully Gully’, ‘Papa-Oom-Mow-Mow’ and ‘Alley Oop’. But the album still needed more ballast and Dean suggested they throw in the old Regents’ hit. With Dean supporting Brian Wilson’s falsetto, ‘Barbara Ann’ rounded off an album recorded and mixed in five days. Subsequent Beach Boys records would take considerably longer to complete, if they ever got finished at all.

Without the band’s knowledge or consent, a Capitol Records employee pulled ‘Barbara Ann’ from the album’s tapes, edited it down from 3:23 to ‘a fast 2:05’, as the ads for the record promised, and watched as it rose to number 2 in the Billboard chart. Variety called the disc a ‘standout swinging item from a recent LP which this combo belts for big returns’. By March 1966, the recording was also riding high in the British charts, competing against the Rolling Stones’ ‘19th Nervous Breakdown’ and the Small Faces’ ‘Sha La La La Lee’. It was followed in April by ‘Sloop John B’, culled from the forthcoming Pet Sounds LP. As were ‘God Only Knows’ in July and ‘Good Vibrations’ in October.

For The Who, what mattered was that ‘Barbara Ann’ was a pop song with a history, yet one that carried no cultural weight or baggage. It was a number they could own in the moment of its performance and immediately after dismiss as irrelevant. That was not something you could do with a cover of a Dylan or Beatles’ composition, but you could do that with The Regents and, perhaps for the very last time, with the Beach Boys. After Brian Wilson was figured as a pop genius, things got more complicated. For The Who, ‘Barbara Ann’ embodied the idea of pop as fun, dumb, impactful and disposable. It was part of their on-going scheme in 1966/67 to high-light the brilliance of pop artifice, to look at themselves reflected in its shinny mirror surfaces and to breathe in its vapours as they floated weightlessly above the solemn and stolid mass of everyday life. The Who’s stance made pop an intrinsic part of their act and art.

In May 1966, prompted by The Beatles’ old publicity agent Derek Taylor, who had relocated to the West Coast and was now acting in the same capacity for the Beach Boys, The Byrds and Paul Revere and the Raiders, Bruce Johnson flew to London to help promote the band’s forthcoming Pet Sounds. As a member, alongside Terry Melcher, of the studio band The Rip Chords, and newly recruited to the Beach Boys to sub on tour for Brian Wilson, Johnson was a key figure within LA’s surf and hot rod music culture. In his English hotel room he played an acetate of Pet Sounds to members of The Beatles and the Stones and made the acquaintance of surf fan, Keith Moon. Johnson and Moon later got together with John Entwistle and the three spent an evening jamming on stage in Romford with Tony Rivers and the Castaways, fellow surf nuts and old mates of Keith. Two days later, Johnson gave an interview at Wembley’s Ready, Steady, Go! studios. He was accompanied by Moon and Entwistle. After the show’s recording, the three dallied in north London long enough to arrive late for an evening Who performance at the Ricky-Tick in Newbury, Berkshire. With assistance from the drummer and bassist of the support band, Daltrey and Townshend had already started the show by the time the trio eventually appeared. Moon and Entwistle took their places, but the tension mounted and erupted into violence, first on stage and then continued later in the dressing room. The Who’s propensity for violence left an indelible mark on the more laid-back Californian; ‘Beach Boy gigs’, remarked Selvin on the event, ‘were not blood sport’. The next morning Johnson flew back to the States.

Ready Steady Go: McGown, Moon and Johnson

The incident makes the front page of the Melody Maker (May 28, 1966)

As July turned into August, The Who recorded three originals – ‘I’m A Boy’, ‘Disguises’ and ‘In the City’. A Keith Moon and John Entwistle composition (with a nod and ten bob to Ronny and the Daytona’s ‘Hey, Little Girl’), the latter was a parody of surf and hot rod music. If you want, they sang, you can surf in the city, swim in its pools and run drag races down its streets. In this impossible compact of London and Los Angeles, the kids are hip and the girls are pretty, and you can do anything you want as there are no rules. To add to the amusingly absurd scenario of surfing London Field’s lido and putting cheater slicks on a Mini Cooper S, The Who were pictured sidewalk surfing on the sheet music for ‘I’m A Boy’. Always out for a lark, they were photographed trying to ride a skateboard in a London park.

At the end of August, ‘I’m A Boy’ b/w ‘In the City’ was released as a single and The Who returned to the recording studio. Alongside ‘Barbara Ann’, ‘Bucket T’ and ‘Batman’, they cut Martha and the Vandellas’ ‘Heatwave’ and the Everly Brothers’ ‘Man With Money’. The Tamla cover would become part of the Quick One album, the Everly’s tune remained in the tape vault. Collectively, the five songs spoke eloquently to the band’s abiding fascination with American pop.

On the 1967 12 track Antipodean album, The Best of the Who, which uniquely collected together all the single and EP tracks between ‘Substitute’ and ‘Pictures of Lily’, making it a solid compliment to A Quick One, the anonymous writer of the sleeve notes detailed the band’s, excepting John’s, musical tastes. Roger liked ‘“quality” negro music such as Wilson Pickett, Otis Redding and the other stars on the American Atlantic label’. Pete had the ‘widest musical taste of any of the group, ranging from Purcell and Bach to modern Electronic Music, incorporating the Everly Brothers and Tamla-Motown on the way’. Keith’s taste ‘lies with the American surfing sound; groups like the Beach Boys, the Rip Chords and Jan and Dean’.

Even if he was often equivocal in his declarations, Townshend too was a fan of the Californian sound. The cataclysmic denouement of My Generation, ‘The Ox’, though credited to the band was based on the foundation of The Surfaries’ ‘Waikiki Run’ – as compelling a statement of the band’s sonic assault tactics as anything found in their portfolio. Reviewing Jan and Dean’s 1965 single, ‘I Found A Girl’, Townshend had said it was more pop art than The Who, which he intended as a high-compliment. In a 1966 photoshoot, held in his Wardour Street ‘bachelor pad’, he posed beside his record collection, which included the Beach Boys’ Surfing Safari alongside Charlie Rich’s Lonely Weekends and Paul Revere and the Raiders’ Just Like Us.

Well after the fact, post-Hendrix’s declaration on his debut album that the listener will never again have to hear surf music, when asked about The Who’s cover versions of surf numbers, Townshend, as if it were all just a brief aberration, would justify it by the band’s need to appease Keith Moon. But, did it really take a whole side of an EP and much of a Ready Steady Go! special to keep Moon happy? Covering ‘Barbara Ann’ alone would surely have sated the drummer’s appetite for singing lead and putting cymbal splashes over the top of everything, yet that song was accompanied by ‘Batman’ and ‘Bucket T’; a TV theme tune with surf music overtones and a hot rod number.

Before being a hit recording for Nashville’s Ronny and the Daytonas, the original Jan and Dean number, ‘Bucket T’, had featured on the ‘Car Side’ of their 1964 album Dead Man’s Curve/New Girl In School. Its thematically mirrored flip side was made up of six tracks all relating to school. In whatever version, ‘Bucket T’ was taken at a lick intended to break the speed limit, which may well have been part of its appeal for The Who. Equally attractive to the band must have been the idea that when sung high and fast ‘bucket t’ sounds like ‘fuck-it-t’. All vulgarity aside, even with an anomalous brass accompaniment, The Who’s version is thin in comparison to the rich, full sound Jan and Dean conjure.

The French horn is not an instrument that springs to mind when contemplating surf and hot rod music, but Entwistle also doused ‘In the City’ with one of his signature parts. Unreleased in the States until it appeared on a 1968 ‘hits’ collection, Magic Bus: On Tour With The Who, ‘Bucket T’ was considered by the band’s European labels to have enough appeal to be coupled with A Quick One album tracks, ‘Run Run Run’ or ‘So Sad About Us’ in Scandinavian markets and, two years later, to sit on the b-side of the German issue of ‘I Can See For Miles’. The attention paid to the track in these markets complicated the idea that it was all just a bit of a Pop art joke, built to be enjoyed and then discarded. Instead, it escaped its context and went fully pop.

Dead Man’s Curve/New Girl In School was not released in the UK, but a 45 of ‘Bucket T’ by the Daytonas was in the shops in February 1966, three months after its American release. The Jan and Dean’s original made its British debut as the b-side to ‘Batman’ in June 1966; a double-header that produced considerable interest on the part of The Who. Despite Ready Steady Who crediting the same writers who penned the top side of the Jan and Dean’s 45 (Berry, Altfield and Weider) for its version of ‘Batman’, it was not the same song. The Who’s cover was a fairly straight rendition of Neal Hefti’s ‘Batman Theme’ though minus the original’s long meandering coda.

Taken from the album Jan and Dean Meet Batman, the duo’s ‘Batman’ was a revisiting of surf city via drag city, final destination Gotham City. The album itself pits the two dynamic duos into the same universe, a pop art melange where the Little Old Lady from Pasadena, escorted across the road by Robin and Batman on the deck of a skateboard, collars the villain. The Who no doubt thoroughly enjoyed its synergies. Provided with a maximum pop framing device, Jan and Dean’s ‘Batman’, like their ‘Drag City’ and ‘Bucket T’, starts with the sound of a revving engine and a squeal of tyres, and ends with a car crash. The sound-effects acting as the aural equivalent of the typographical animated overlays in a fight scene from the TV series – KaPow! By comparison, The Who’s ‘Batman’ is a sparse affair. It lacks the underlying sonic aggression of Link Wray’s version, the souped-up rubber burn of The Marketts’ cover, or the funk of the Sensational Guitars of Dan and Dale (moonlighting Sun Ra Arkestra and Blues Project band members)

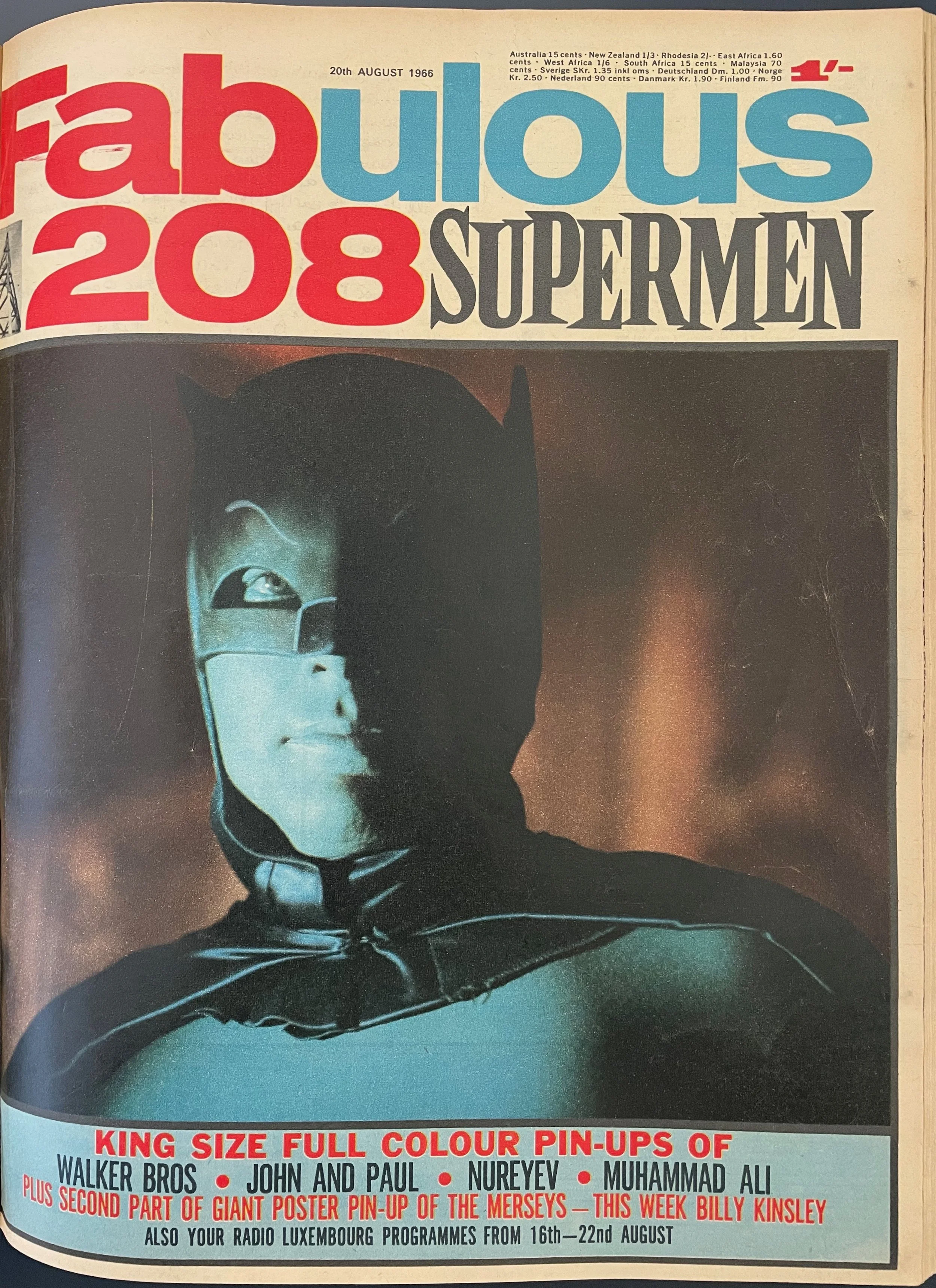

The UK’s independent ABC-TV had bought Batman for the record price of $4,000 per 30 minute episode, typical costs of imported American series were around $2500. Broadcasts started at the end of May for the midlands and the north. Rediffusion bought the rights for London and begun transmission of the programme in July. In the States, the series had begun production in October of the previous year and the pilot was broadcast on January 12, 1966. Pre-sales to advertisers, like Kelloggs, were fiercely competitive and companies were quick to promote spin-off goods aimed at the youth market, including toys, clothing, games, and candy. A San Francisco nightclub was renamed after the show, its go-go dancers disported themselves in topless Batman and Robin costumes, and a new dance was coined, the Batusi. In the UK, following the sale of the series, over 20 companies negotiated licenses to produce Batman branded goods.

Nico as Batman Warhol as Boy Wonder

From the Summer into the winter months of 1966, Batman was the rage. Its appeal was to a diverse demographic, something that had been scripted in from the beginning:

Batman is being cranked up with all the slambang antics kiddies are said to relish, but the overtones are unmistakably aimed for ‘camp’-following elders. The Bat himself is, first of all, a clean cut exaggeration – stepping up to a bar in full regalia and ordering a tall orange juice. His technique with femme runs to lines such as ‘You interest me, strangely’. You know it’s camp because the particular line is addressed to Jill St. John, strangely.

Batman the TV series was pre-planned camp, not inadvertent camp like the 1965 revival of the 1943 film serial that became a rage with metropolitan film fans both in the States and in Europe.

‘High Camp. . . Made in ‘43 . . . Discovered in ‘65’

As for its exploitation angles, Variety explained that these included plans for an exhibition of ‘Batmania’ at Manhattan’s Guggenheim museum:

With or without his presence, this could stimulate some fresh dazzling quotes from pop-art high priest Andy Warhol, who might be stimulated to attempt a nine-hour flick of the Batman torso. (Toss in a two-hour ‘short’ of young Robin and you have a long day’s night for fair).

The show’s uniqueness then, as Variety pointed out, was ‘comic book camp’, or what art critic Lawrence Alloway called Third Phase Pop Art. That trend followed on from when pop culture was first taken seriously by art critics in the 1950s and then, in its subsequent stage, it became the actual subject of the high arts, as exemplified by Warhol et al. The final shift was when the original signifiers used in Pop art, comic book imagery (Batman), film icons (Marilyn Monroe), commercial products (Coca-Cola) were re-appropriated by commercial interests but now had added cultural value gained by the encounter with the fine arts.

Not that Variety’s reviewer was convinced about any of this:

The show’s most serious flaw, which could chase off some early rooters, is a basic one, that of international camp, or the tendency to parody parody. In last week’s premier segs, the campiness all but dissipated under the arches, and the result was more on of the strained cutes.

This is doubtless irrelevant for the kids, for the Bat loads up on the simplistic action in the standard kidvid vein. It moves with a succession of short bursts and quick cuts.

That the series would hold the attention of that segment of the British market who were sold on pop was a given. Rave magazine had it covered: ‘Batman and his sidekick Robin are definitely THE biggest new vogue for quite a while. . . Stateside, anything to do with bats, capes and Batman is ‘IN’. Girls go for a Bat Cut hairstyle, a short cut with points on the face.’ Disc and Music Echo asked the stars for their response to the series; Steve Marriott thought the old Saturday morning serials ‘were funnier than today’s versions because they weren’t meant to be funny’; The Who are such ‘avid fans that they have dedicated a track on their latest EP to Batman. “He’s fantastic”, says John Entwistle. “it’s very good if you look at it as a comedy show. But most people don’t – they look at it as a straight show with lousy production.”’

The Who had promoted their second single, ‘Anyway Anyhow Anywhere’ as a pop art event: ‘A Pop-Art group with a Pop Art sound . . . Pow!’ That onomatopoeia reappeared on some of the advertising materials for their debut album, My Generation. ‘Substitute’ was marketed with an image of an atomic mushroom cloud, suggesting the single packed a BIG punch. Some of the advertising for ‘I’m A Boy’ similarly hinted at its potential impact, and used the cartoon exclamation ‘KAPOW!’ that came straight out of the Batman–Pop art play book.

Paul Jones, Record Mirror’s centrefold (July 9, 1966)

In the same week as the ‘I’m A Boy’ advert was run in Record Mirror, Disc and Music Echo featured The Who announcing the death of their Pop art affectations:

‘The Who were the first people in the world to wear pop art clothes, it was an absolute scoop’, said group’s manager Kit Lambert . . . ‘We have finished with pop art in a way’, said Pete. ‘Though we are not completely departing from it. For instance, we are thinking of starting one of our TV programmes by bursting in through Union Jacks. It will be to show group development, presenting the Who as they were a year ago. But that’s all it amounts to now with us – group history. We’ve passed the stage where we used it as a great promotional idea. We don’t need that now.’

But if the band were coming across as schizophrenic, uncertain whether or not it was a Pop art group with a Pop art sound, pop, never mind art, really did still matter. In a column listing his likes and dislikes, his favourite colour (‘dark crumbly brown’), Townshend rated some recent records, including Bobby Darin’s (‘If I Were A Carpenter’) ‘Fantastic! Everyone’s very pleased about it’, the Spencer Davis Group’s ‘Gimme Some Loving’, which he liked (he had ‘hated their last one, though’), and the Four Tops’ ‘Reach Out and I’ll Be There’. He wanted to see the latter live, to hear what they’ll do with the song, which he called a ‘joker record . . . Someone’s always playing a wrong note’. As for the Beach Boys’ ‘Good Vibrations’, released in the UK at the end of October, he claimed to have ‘Heard it 80 times – but only just begun to like it.’

As Christmas loomed, Townshend, promoting A Quick One, continued to extemporise on the topic of what made for a good pop record. He told Penny Valentine that Brian Wilson was ‘making pop music too complex’, he ‘lives in a world of flowers, butterflies and strawberry flavoured chewing gum. His world has nothing to do with pop. Pop is going out on the road, getting drunk and meeting the kids. “Good Vibrations” was probably a good record but who’s to know? You had to play it about ninety bloody times to even hear what they were singing about.’ Six months before the release of Sgt. Pepper and Townshend is reading the runes as well, if not better, than anyone else:

Look, the kids just don’t know what’s going on, everything so involved. Next year is going to be worse. We’re going to have a batch of over-produced Beach Boys records and over-produced records in general. Andy Warhol (leader of America’s plastic pop brigade) will come over and start on his psychedelic bit and everyone will walk around saying ‘oh yeah that’s what I thought all the time’. And the first person to explain it like that will cop the money.

Reports about the Velvet Underground and the Exploding Plastic Inevitable had obviously reached Townshend but, whatever he feared that might augur for pop, he still put his trust in the Beatles:

It needs the Beatles to come out of their hole and make a really simple pop record to sort things out. I’d prefer to see a reversion to pop for a pop audience. It’s all wrong to elevate a pop audience to what you’re doing. We made that mistake early on. We had no plans to escalate as quickly as we did musically. We used ideas we didn’t even understand ourselves never mind anyone else not understanding them.

Getting back to involved pop music, I’d like people to think we kept things simple and not over-thought. I mean I’d hate people to think we’d actually put a load of thought into A Quick One. We just went into the studio, got into a drunken coma, and had a ball.

Record Mirror thought A Quick One album was better than the ‘pop art sound of the My Generation era.’ The Who’s music was now ‘more subtle’ almost with a ‘Beach Boys approach, well vocally anyway . . . Best track is the ‘Quick One’ saga which sounds like Pet Sounds LP squeezed into one long song’. Given Townshend’s recent critique of Wilson’s overproduced, overly self-conscious pop, there’s some irony in the reviewer’s claim that the band not only sing like the Beach Boys, but the album’s key track even sounds like them.

For The Who, however, the contradictions in their public communications, indeed in their music, did not need to be worked out, effaced or denied, it was core to their act, to their identity, their appeal. The EP was all about riding the line between art for art’s sake and pop for pop’s sake. This was what The Who with Ready Steady Who, onto A Quick One, right through The Who Sell Out and into Tommy, embodied. KaPow!

Ladies Home Journal (April 1966)