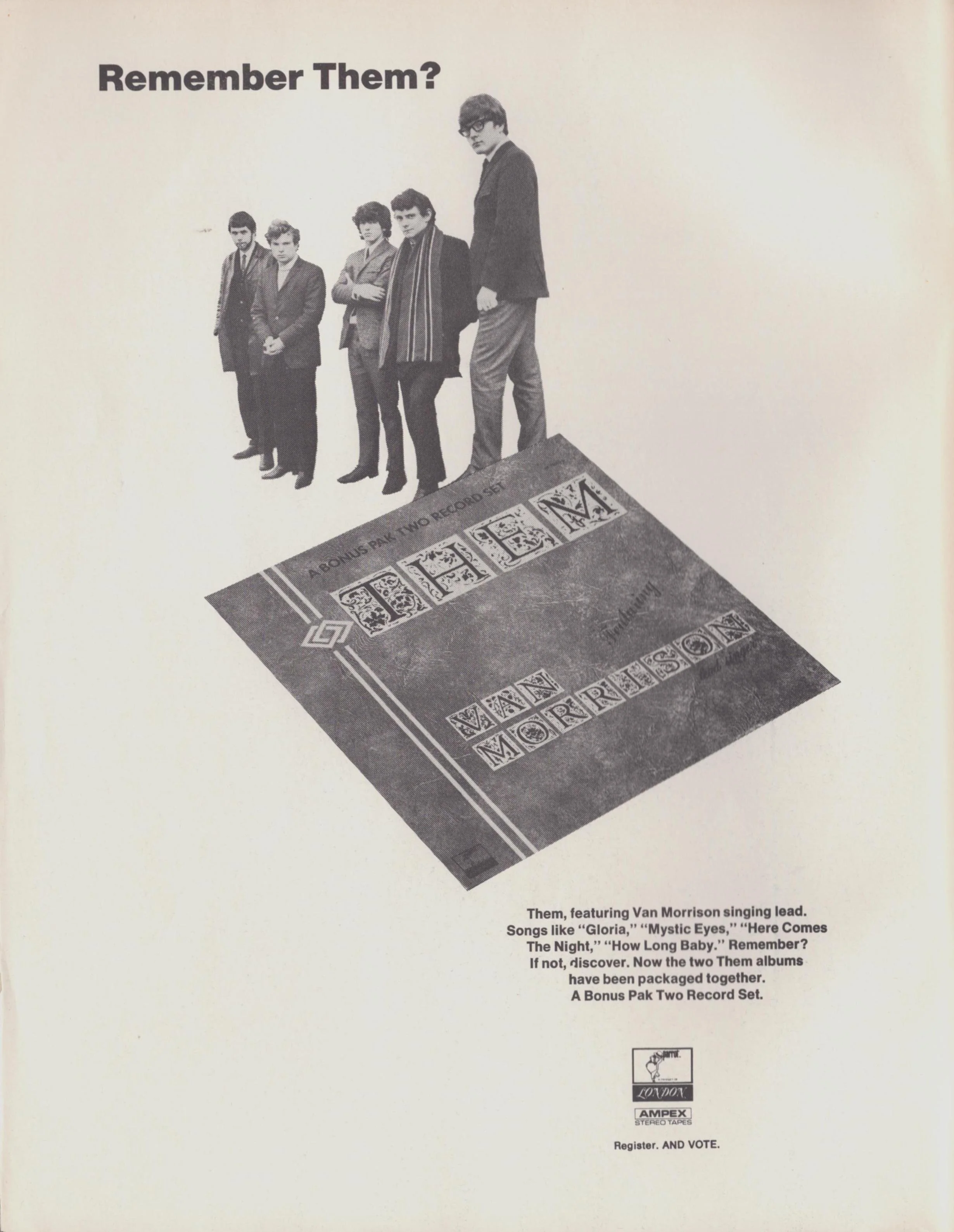

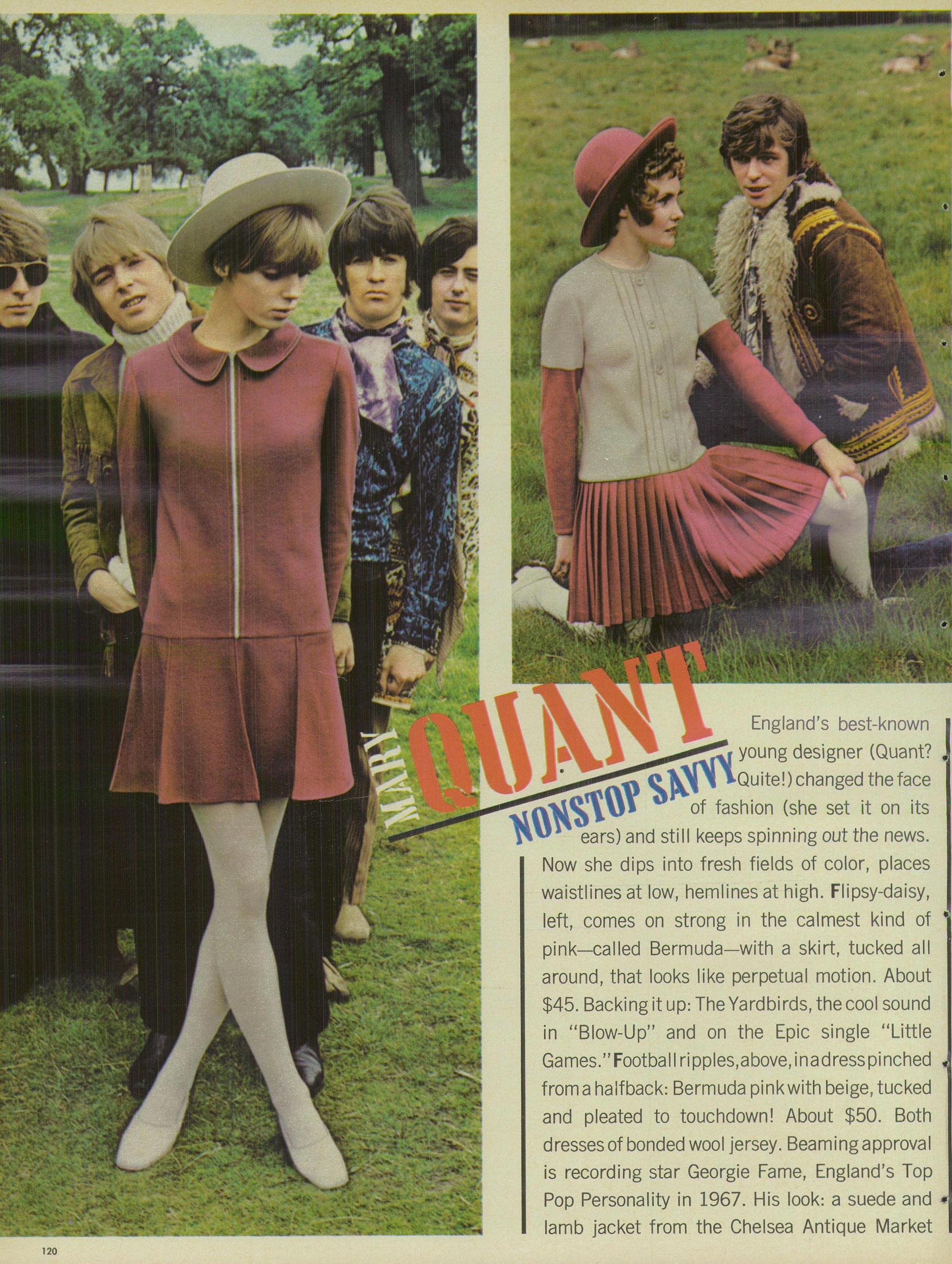

"It's a shame the Yardbirds have no image," opined Herman's Hermits' Peter Noone bluntly in 1966, "because they would be the Number One group in England." It's true that the Yardbirds—whose "magnificent reverberations" are chronicled in Peter Stanfield's "The Yardbirds: The Most Blueswailing Futuristic Way-Out Heavy Beat Sound"—remain a difficult band to peg among their peers. They were tricky to market, too, stiff and uncomfortable in publicity photos. Despite the powerful, affectless voice of their singer Keith Relf, the Yardbirds frontman offered no Mick Jagger-like threat to the female populace. One British magazine described him as "frail like a sparrow," more likely to engender maternal feelings in its teen readership.

In any case it was its succession of genius guitarists to whom the rest of the band was in thrall. The sequence included Eric Clapton, who left in 1965 over a mix of personality clashes and his own blues orthodoxy. He was followed by sonic adventurer Jeff Beck, who moved front and center with his arsenal of fuzz, distortion and feedback, and, finally, Jimmy Page, who arrived in 1966 as a bassist but graduated to guitar, violin bow in hand, foot rocking on the wah-wah pedal. Their classic mid-'60s lineup included Chris Dreja on rhythm guitar, bassist Paul Samwell-Smith and Jim McCarty on drums (the sole original member in the current iteration of the band).

The London rhythm-and-blues scene—including the Crawdaddy Club, where the Rolling Stones were launched—gave the Yardbirds their start. Their signature was the "blueswailing" rave-up, the instrumental interlude that could stretch any three-minute number into a sweaty epic jam, feeding off the proximity of an audience moving, in the words of one contemporary journalist, "like a crazy caterpillar on pep pills." Their debut album, "Five Live Yardbirds," recorded at the Marquee Club in 1964, would later be tagged by All Music Guide as "the best such live record of the entire middle of the decade."

After Mr. Clapton's departure, the Yardbirds gravitated toward commercial pop ("For Your Love," 1965), then pioneered psychedelia ("Shapes of Things," 1966) before unexpectedly and ill-advisedly joining forces with Mickie Most, the producer of acts such as Herman's Hermits and Donovan. When Relf and Mr. McCarty left in 1968, Mr. Page, in pursuit of a "heavy beat sound," recruited new members into an act that briefly toured as the New Yardbirds. They re-formed as Led Zeppelin, inheriting some Yardbirds tunes including the staple "Dazed and Confused."

Though the Yardbirds produced a string of groundbreaking singles, notably during Mr. Beck's tenure, casual listeners today might have trouble naming any of their songs beyond "For Your Love"—perhaps because the band's obsession with experimentation and novelty made their musical style protean. Singles such as "Shapes of Things" and the follow-up, "Over Under Sideways Down," are like small suites lurching between sections that seem to cohere only by force of will: The Animals' Alan Price disparaged these as "jigsaw puzzle" records, presumably less than the sum of their parts.

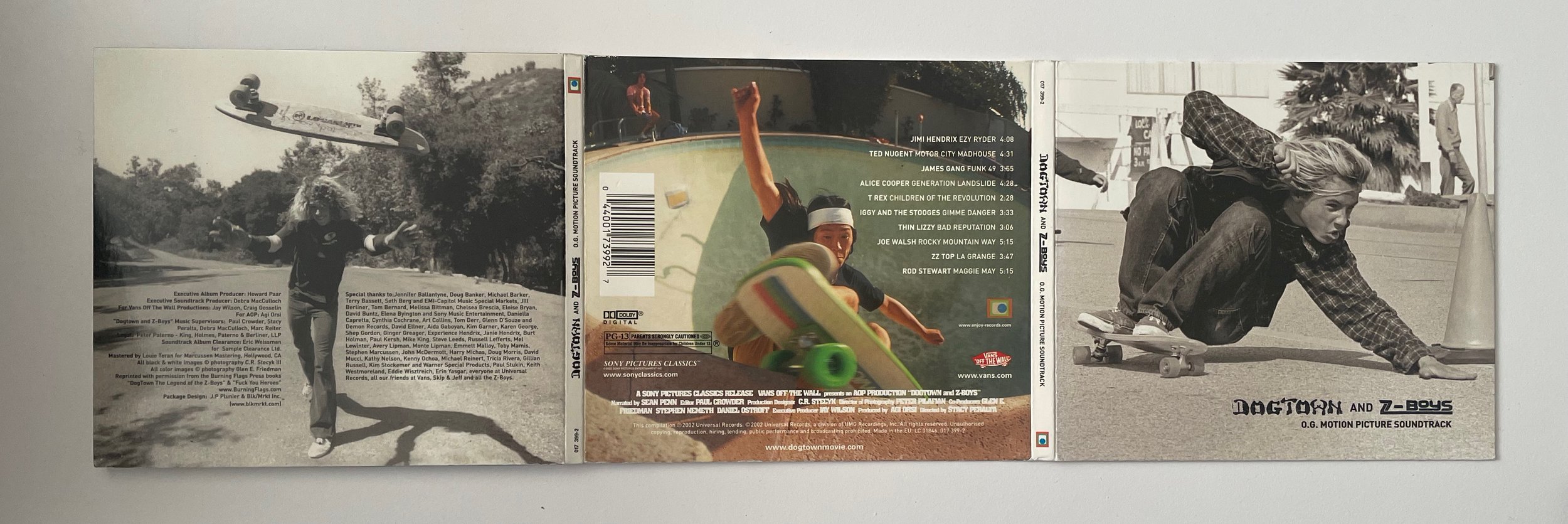

The Yardbirds' 1968 breakup caused barely a ripple, but their influence has endured, despite the overshadowing presence of the bands that emerged from their ruins: Led Zeppelin, the Jeff Beck Group, Renaissance and Cream. In December 2021, Rolling Stone magazine's list of the 100 greatest guitarists of all time counted Mr. Clapton, Mr. Beck and Mr. Page among the top five (Jimi Hendrix took the top honors).

This assiduously researched, strictly chronological study says "Yardbirds" on the cover, but its best passages anatomize the various scenes—from the British blues explosion to the through-the-looking-glass moment of psychedelia—negotiated by a band trying to keep ahead of the pack while popular music was "evolving at a pace few could have anticipated." The author is particularly good on what Kurt Cobain called "territorial pissings"—in this case those of the '60s blues purists who did battle with the bandwagon-jumpers in endless arguments about "authenticity." Mr. Stanfield is also persuasive about the long arm of the Yardbirds' influence. David Bowie's 1973 covers album "Pin-Ups" featured two Yardbirds numbers: "I Wish You Would" (1964) and "Shapes of Things." The author suggests that Relf's impact as a vocalist would be felt even later, in the punk delivery of Johnny Rotten and others.

"The Yardbirds" draws heavily on primary sources, reviews and interviews from the national and regional press of the day (notable sources include the Port Talbot Guardian and the Lincolnshire Echo). This approach yields freshness via some of the scandalized descriptions of then-new dance styles—"Imagine Frankenstein's monster trying to walk like a penguin and you have a rough idea." Too often, however, those in-the-moment reviews are variations on a single theme, and their lack of perspective becomes wearying. Mr. Stanfield is at his sources' mercy and you can hear a slight groan as he acknowledges: "The bands' ceaseless touring of Europe . . . meant that they were all but invisible in the British music press throughout the year."

Yet this time-machine technique provides glimpses of a lost world in which pop music was developing at a furious pace, and Mr. Samwell-Smith could seriously claim to be "too old . . . at 23, to play the pop game with any conviction." Relf displays disarming honesty as he tells an interviewer "We need a hit badly." Equally quaint are the band's aspirational claims for the "futurism" of their sound, as Relf rebrands their sonic approach "abstract expressionism." The Yardbirds had a cameo in Michelangelo Antonioni's 1966 film "Blow-Up"—but only after the Who turned down the offer.

Because much of the band's turmoil was kept from the press at the time, Mr. Stanfield's approach drains some excitement out of the Yardbirds' story. We get only a glancing view of many triumphs and crises: the catastrophic decisions of bad management, dodgy business deals, nervous breakdowns, sensational fretwork, ill health and plenty of infighting. Though the book never quite reaches the music's frenzied pitch, its reconsideration of the ambition of the Yardbirds is welcome. The band was "without peer as a live attraction," and Mr. Stanfield makes one want to step back in time into one of those packed clubs, so hot that, as one writer of the day put it, "you could have boiled an egg."

By Wesley Stace

Mr. Stace is a novelist, a singer-songwriter and the master of ceremonies of Wesley Stace's Cabinet of Wonders.