The Last Movie montage from Seventeen (July 1970)

From the late 1960s into the mid-1970s, the traditional wellspring of American cinema was threatened, redirected, and ultimately enriched by the emergence of what came to be known as “New Hollywood.” This was an era in which young filmmakers, actors, musicians, and other creatives carved out a cultural niche which still endures in the imagination and aspirations of many people across the globe almost 60 years later. It is this epoch which animates Peter Stanfield’s Dirty Real: Exile on Hollywood and Vine with the Gin Mill Cowboys, published by Reaktion Books.

The titular “Dirty Real” refers to a decidedly bohemian lifestyle which could include a rootless existence with spartan lodgings when on the road, a cultivated inattentiveness to appearance (clothes/hair/hygiene), conspicuous and guilt free pleasure seeking (sex/drugs/alcohol), and a rejection of the establishment (school/work/family/capitalism), all of which represented an alternative version of that great American ambition, freedom. It was this aesthetic, manifest in the setting, plot, characterization, and soundtracks of several dozen films in the late 1960s-early 1970s which Stanfield posits as the core of the “Dirty Real” canon.

A running theme in the book is the quest for the authentic “dirt,” a commodity which the filmmakers and actors took great pride in pursuing, accomplishing and presenting to an audience with an appetite for such fare and apparently an ambition or fantasy to pursue that life for themselves. Nonetheless, Stanfield argues that these actors, directors, writers, and their productions fell short of legitimacy. In its filmic form it was modification, affectation and ultimately commodification of the genuine Dirty Real. On the faux authenticity of the Dirty Real filmmakers, Stanfield proclaims “the trick they pulled off was to suggest they had gained it by hard-scrabble labour, from experience earned on the road, with sweat and dirt honestly come by. In self-defined exile, with their privilege hiding in plain sight, they had this tale to tell, and they told it with glorious, splendid elan” (40).

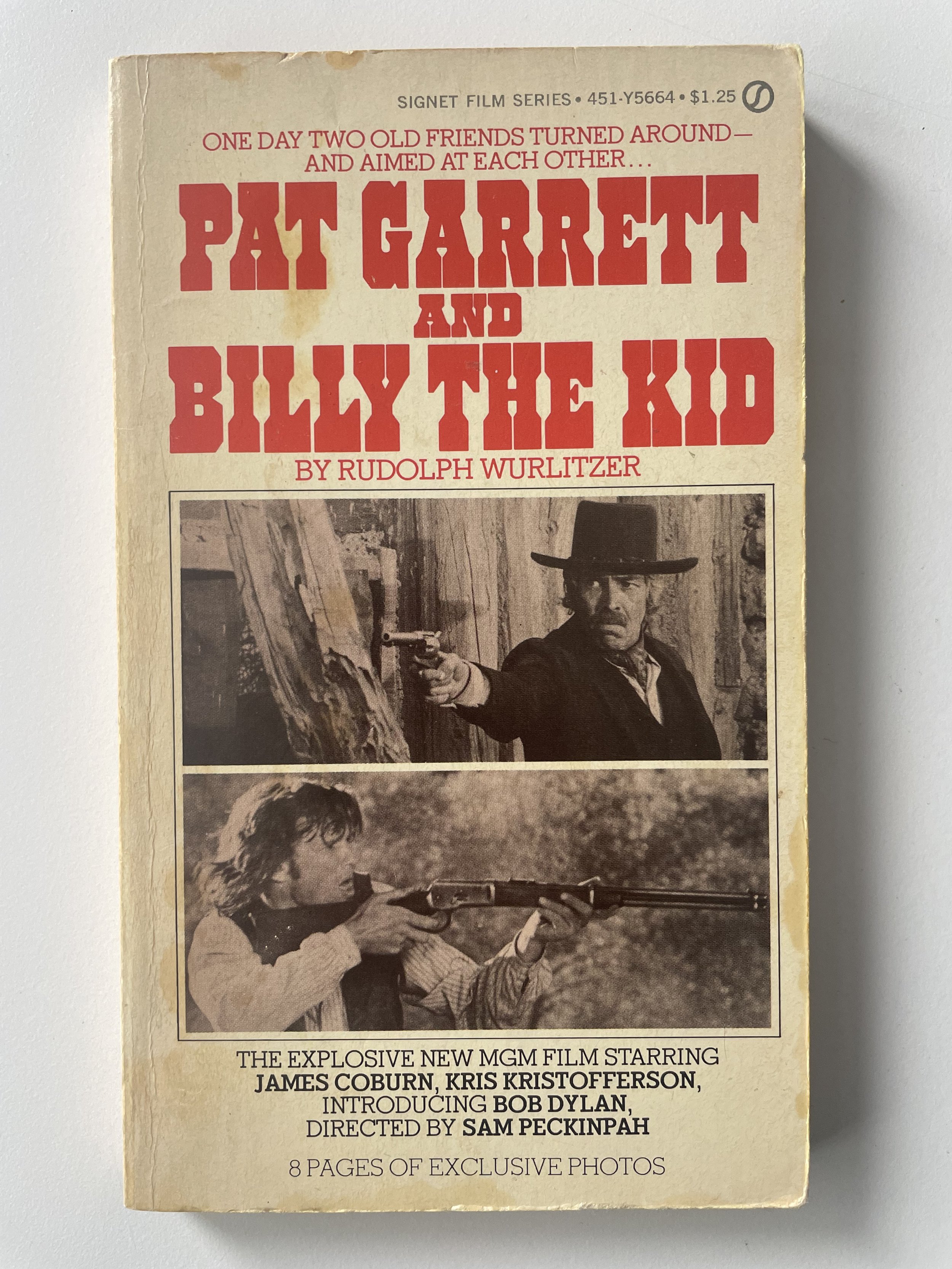

The author also notes that this emerging genre was not fully original, but rather inspired by old archetypes which were re-booted in the late 1960s and early 1970s. For example, in New Hollywood’s contemporary action films, the lead characters rode motorcycles and drove souped-up cars (Easy Rider, Bonnie and Clyde, Two-Lane Blacktop), and in the new historical westerns (The Hired Hand, The Wild Bunch, Dirty Little Billy, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid) the cowboys and criminals were often morally ambiguous misfits whose licentiousness, remorseless violence, and anti-social behavior is often accepted without the judgement and punishment that was expected in Old Hollywood productions. Stanfield also marks a mid-sixties revival in the iconic films and persona of Humprey Bogart as a benchmark in the rise of Dirty Real. As he remarks, “For the film-makers of New Hollywood, Bogart was not only a figure they might identify with, he was also someone they would refract in their own anti-heroes” (13), albeit in films that were infused with unfettered permissiveness (sex and violence), unvarnished cynicism, ambiguous heroism and without the obligatory happy or just ending.

In one final blow to authenticity of the Dirty Real film community, Stanfield notes the symbiotic, or was it mutually parasitic, relationship between the new American cinema and the rock/pop music of the era. It seems the Dirty Real “street cred” of New Hollywood was enhanced by the close association with the world of pop-rock music, particularly in the eyes of a youthful audience. Putting aside the possible appropriation of pop music’s hip grittiness, it is hard to imagine many of the most iconic films of this era without their rock soundtrack, and it seems beyond question that the music enhanced both the films and the status of the musical acts. One of the unexpected and defining elements of Dirty Real is Stanfield’s analysis of the role of popular music in many of the films and the way the pop/rock culture informed the Dirty Real aesthetic.

The book has eight chapters bookended by a scene setting introduction and brief conclusion. Each chapter is thematic and anchored by a focus on one or more films: Chapter One: The Hired Hand; Chapter Two: The Last Movie; Chapter Three: The Last Picture Show, Five Easy Pieces, and Payday; Chapter Four: The Shooting, Ride in the Whirlwind, and Two-Lane Blacktop; Chapter Five: Cisco Pike; Chapter Six: Dirty Little Billy; Chapter Seven: McCabe and Mrs Miller; Chapter Eight: Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid.

The Hired Hand

The analysis in the chapters is comprehensive in its coverage of each film and its place within the genre and in the zeitgeist of the era. This includes a detailed account of the film’s plot, in-depth character studies, as well as a deconstruction of the central conflicts which drive the story and motivate each role. Stanfield also adroitly links elements of these “dirty” films with dozens of other productions from various decades. Ample time is also dedicated to how the films were received after release, encompassing film critics, box office receipts and the engagement of the general public. Readers who enjoy behind the scenes content will find details on financing, casting, inter-personal drama, and the jockeying for credit and acclaim in the face of success. Additionally, the author offers an examination of many of the actors, writers, and directors who rose to fame in the New Hollywood, in what amount to mini era-specific biographies of personalities such as Jack Nicholson, Peter Fonda, Dennis Hopper, Peter Bogdanovich, Monte Hellman, James Taylor, Kris Kristofferson, Robert Altman, Sam Peckinpah, and Bob Dylan. This list of people highlights the predominance of white males in this era, a fact to which the author alludes but does not extensively analyze.

Stanfield supports his narrative with ample endnotes for each chapter, including sources ranging from academic publications to contemporary periodicals to memoirs and mass market biographies. Additionally, there is a bibliography and selected filmography which highlights the films discussed in the text. The book is also populated by thirty-two illustrations presenting movie posters, commercial ads, album covers, and movie stills.

Dirty Real offers great utility in an array of academic disciplines including American Studies, Media/Communications, Musicology, and Film Studies at both the undergraduate and graduate levels. The book would also be of interest to cinephiles and general audiences because of its engagement with iconic films, music, and cultural touchstones and characters who retain a measure of recognition and relevance fifty years after their artistic hightide began to ebb.

Stanfield’s great accomplishment with Dirty Real is to highlight and cut through the posing pretentiousness of these filmmakers, actors and writers to reveal the cultural/social artifice that imbued so much of the 1960s–1970s New Hollywood filmography. Yet he also manages to express his admiration for their artistic endeavors; he does not discount the quality, value, and impact of many of these films. As Stanfield says, “The films’ characters, as with the actors, writers and directors, were costumed in the pitch that defileth and showed too an acute nostalgia for the gutter none had known at first hand. For a cool moment they almost turned Hollywood into an image of themselves” (8–9).

Madison Ave gets Dirty Real: Left, Dirty Little Billy director Stan Dragoti. Middle, Jack L. Warner, producer, and Cheryl Tiegs, Sports Illustrated cover star and married to Dragoti

Michael McKenna – professor of history, politics, and geography at Farmingdale State College