Casting two musicians with zero acting experience (and without much ability in that field) in the leading roles and then not catering to their fan base by exploiting the very thing they are actually good at, is just perverse. But such obstinacy is also entirely in keeping with Monte Hellman’s intent to shut down any ‘detrimental empathy’ such musical moments might generate. In Two-Lane Blacktop James Taylor doesn’t get to sing and Dennis Wilson doesn’t sit behind him on drums or provide harmonising vocals because in the film one drives a car and the other keeps it on the road. That’s it.

The important thing was the characters Taylor and Wilson were playing, Driver and Mechanic respectively. Having them sing would have diminished their parts, helping to undermine an audience’s willingness to suspend disbelief and forge an identification with the protagonists. Taylor performing ‘Sweet Baby James’ would have been a distraction. Besides, Two-Lane Blacktop was a film that worked assiduously against cliché and convention. This was a movie about a race that never gets going and so is never concluded; it’s a road movie that goes nowhere. It’s also a love story between two men and a woman that might evoke Jules et Jim or Bande á part but generates so little frisson between the three leads that it is, in contrast, a despondent and loveless affair.

Excluding any music that doesn’t have an identifiable source, especially that for which the actors are known for, was therefore non-negotiable for Hellman. Following Easy Rider, a soundtrack filled with contemporary recordings must have been part of the film’s financiers’ expectations along with the anticipation of seeing it replicate the box office appeal of Hopper and Fonda’s little picture.

In the Spring of 1971 Esquire put an image of the Girl, played by Laurie Bird, hitchhiking on its cover and gave over thirteen of its pages to the film’s screenplay, an unprecedented bit of promotion for any movie:

‘Read it first! Our nomination for the movie of the year: Two-Lane Blacktop – Where the road is and where it is going: the first movie worth reading.’

The hype crashed on the film’s release and Esquire turned on it:

‘the film is vapid: the photography arch and tricky and naturally, therefore, poorly lit and unfocused; the acting (only one part is played by a professional) amateurish, disingenuous and wooden; the direction inverted to the degree that fundamental relationships become incidental to the film’s purpose. The script has become the victim of the auteur principle’.

The film is remarkably faithful to the published screenplay, there are around half-a-dozen small scenes that didn’t make the cut, including a couple of sex scenes and some nudity, but those differences would not be why the magazine considered the screenplay a success and the film to be a bore. Hellman said he took out the skinny dipping scene because it held up the action, but what action? One thing the screenplay does that the film hides and obscures is to give the reader the sense that pop music, of various sorts, accompanies and comments on what’s being shown on the screen, giving it the same level of heightened interaction that was experienced when watching Fonda and Hopper scoot down the highway as Jimi Hendrix or Steppenwolf played over the cinema’s sound system.

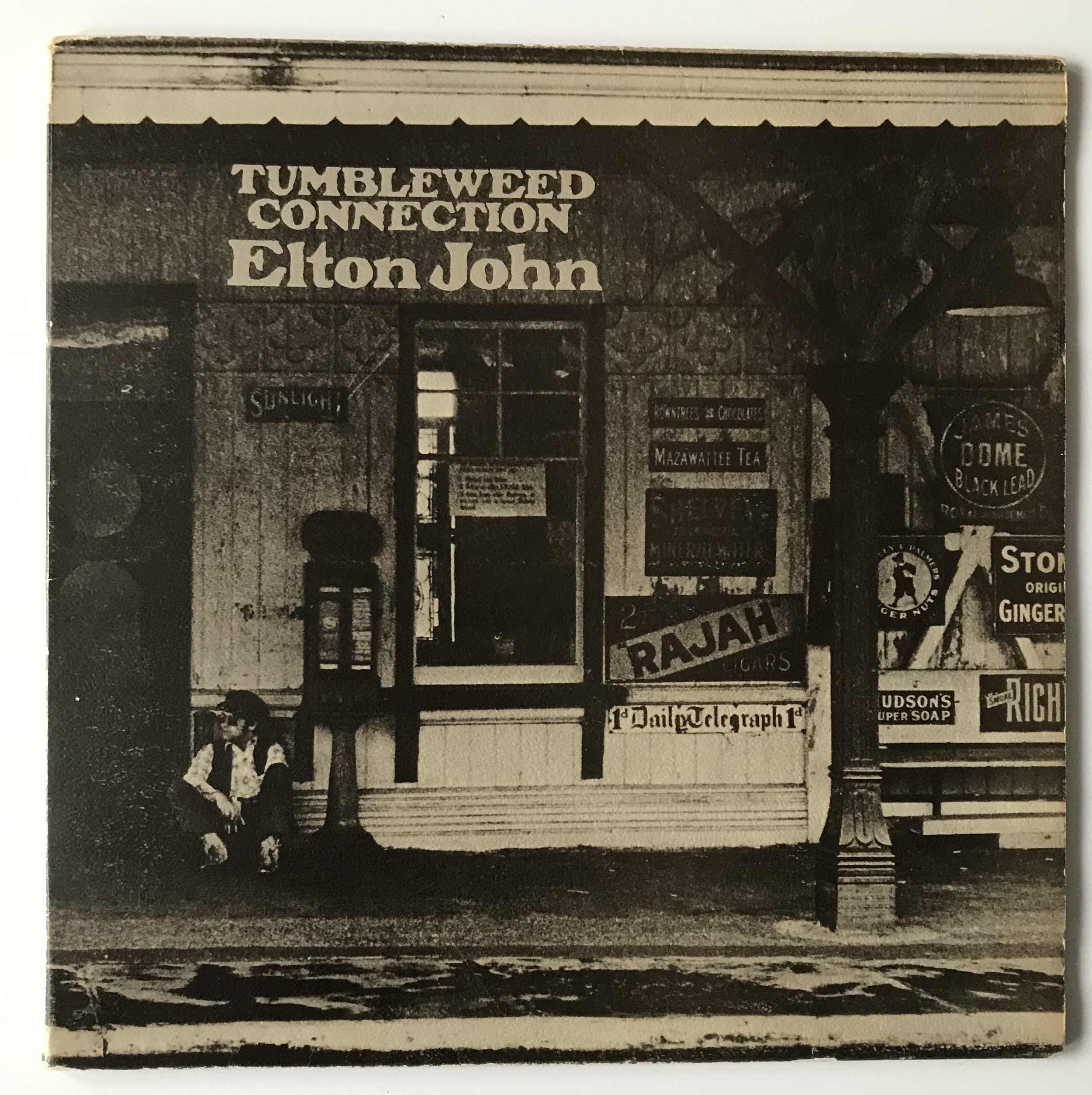

The portrait of Taylor that sold him to Hellman as the man for the part of Driver, Sweet Baby James

Taylor never saw the film and never acted again, but he did like Richard Avedon’s publicity photographs enough to use a couple on his 1974 album Walking Man

Four Rolling Stones recordings are mentioned in the screenplay, ‘Satisfaction’, ‘I’m Free’, ‘Time is on My Side’ and ‘Honky Tonk Woman’, each one would work as a meta-commentary on the action, just as Ray Charles’ ‘Hit the Road Jack’ or Chuck Berry’s ‘Maybelline’ and ‘No Money Down’ run in parallel, supporting or satirically pricking what is being seen. The Doors’ ‘Break on Through’ and Ike and Tina Turner’s ‘You Got What You Wanted’ are others that fitted, in this manner, directly into the scheme of things.

Two-page spread from Show magazine that puts the emphasis on Laurie Bird, naked if she wants to (stills from a scene cut from movie)

Cassettes are popped into GTO’s deck throughout the screenplay, bluegrass at one point, which would have evoked Bonnie and Clyde’s mad dashes down country roads. Hank Snow plays on the radio, like the bluegrass emphasising the not-so-merry band’s movement through rural communities. The Girl, who can’t hold a tune to save her life, sings old blues stanzas in the back of the Chevy, including a few lines from ‘Easy Rider’ giving a knowing nod to the movie’s predecessor. Cumulatively, the song references make for a potentially great soundtrack and imply a set of personal, finger-snapping connections, moments of familiarity with a shared cultural locus that had the potential to cement a relationship between the viewer and the film in the same manner as Mean Streets. But what you get is something else.

Under the noises of revving engines and chatter the Doors’ ‘Moonlight Drive’ plays on

Here’s the song list as used in the film (it’s from IMDB with a couple of amendments):

‘Moonlight Drive’ – The Doors

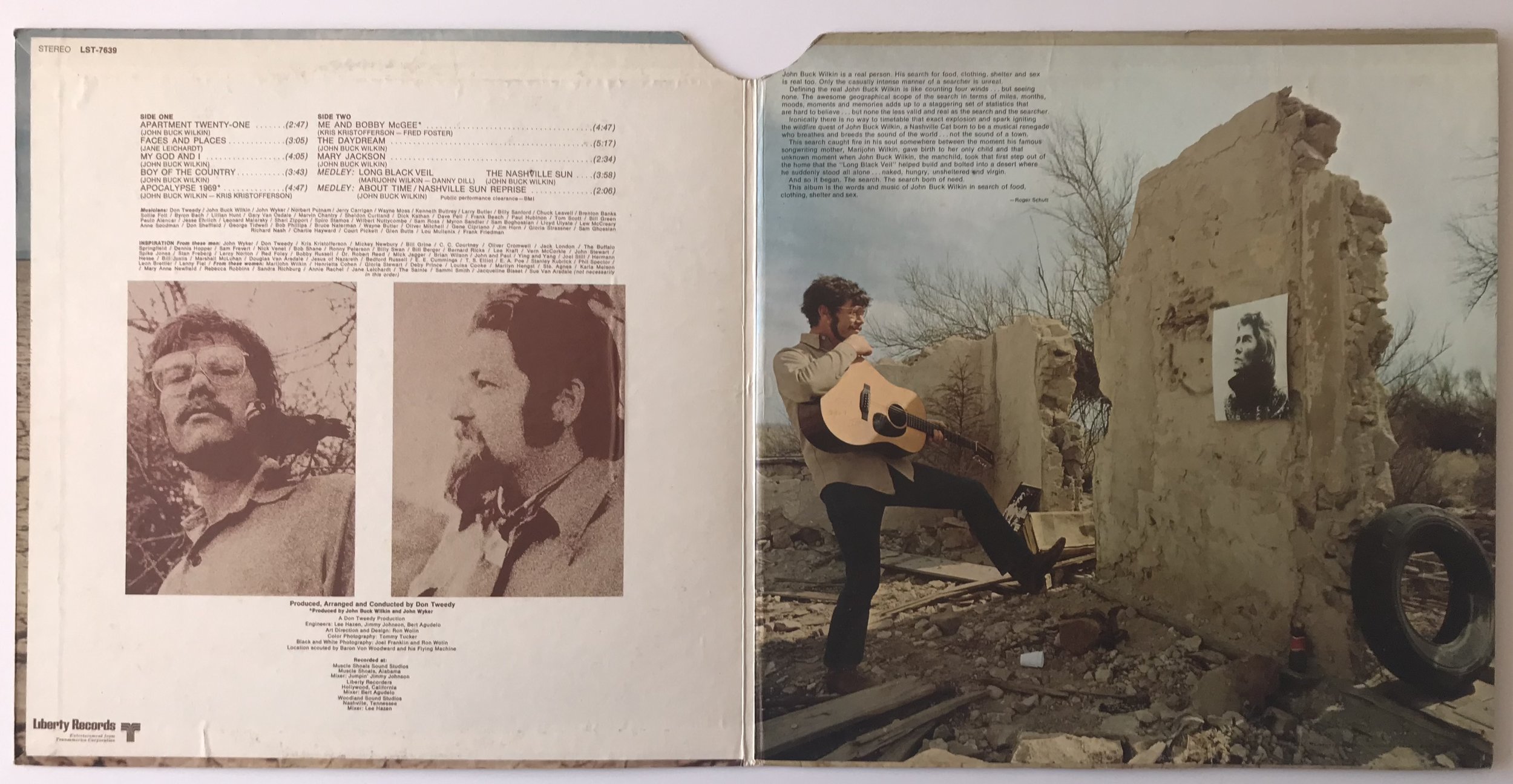

‘Me and Bobby McGee’ – Kris Kristofferson

‘Maybelline’ / ‘No Money Down’ –John Hammond Jr.

‘Stealin'’– Arlo Guthrie (and Laurie Bird)

‘Hit the Road Jack’ – Jerry Lee Lewis

‘Satisfaction’ – Laurie Bird

‘Taylor Made’ (Instrumental) – Hal Mooney

‘Song in Gee’ – Lisa Gilkyson

‘Early Cocktail’ – Ole Georg aka Henrik Nielsen

‘Peace in the Valley’ – anonymous

‘Cattle Call’ – Eddy Arnold

‘Girl of My Dreams’ – James Kenelm Clarke

‘John Henry’ – Kentucky Colonels with Clarence White

The cost of licensing the Stones precluded their inclusion, though Laurie Bird sings an off-key version of ‘Satisfaction’ as she gravitates toward a pinball machine in a diner. One contemporary account reported that she also attempted to sing The Doors’ ‘When You’re Strange’, but that’s not included, and ‘Break on Through’, referenced in the screenplay, is replaced by ‘Moonlight Drive’. The latter is buried deep within the mix beneath revving engines and squealing tyres. Chuck’s songs are present but sung by John Hammond, Jerry Lee Lewis deputises for Ray Charles and, instead of Hank Snow, we get Eddy Arnold. Ike and Tina don’t make the grade in any form, faded out alongside the ambition the filmmakers once held for the role of commercially available recordings.

Laurie Bird in Elvis shirt, not featured in the film and neither was the horse

The one song that does get a platform in the film is Kris Kristofferson’s ‘Me and Bobby McGee’. Cover versions had been hits on the Country and Pop charts for Roger Miller, Gordon Lightfoot, Charley Pride and was a posthumous number one for Janis Joplin. Even Jerry Lee Lewis took it into Billboard’s Hot 100 before the end of 1971. The song is not listed in any of the published screenplays. Much of this interest in it took place in the latter stages of the film’s post-production, which meant the song had a contemporaneity and an immediacy that would have connected with the film’s original audience. On the other hand, ‘Bobby McGee’ is the very thing Hellman had elsewhere avoided, cliché. But there it is, all but asking the audience to make a connection with its romantic sentiments – detrimental empathy – even as the film elsewhere refused to be drawn in that direction. Besides, ‘Me and Bobby McGee’ was also featured that year in Dennis Hopper’s The Last Movie.

Writing for Show magazine, Shelley Benoit spent a week on location with crew and actors in Tucumcari, New Mexico. One of those days was spent filming in a diner: ‘The jukebox in this forlorn spot affords one Beatles, no Stones and a whole lot of Merle Haggard’. Two-Lane Blacktop seemed to have become stuck with that selection. Such a fact probably hurt the film at the box office and with its critics, but 50-years on from its release Monte Hellman called it right. Have no doubt.