‘Come on, let’s drift.’

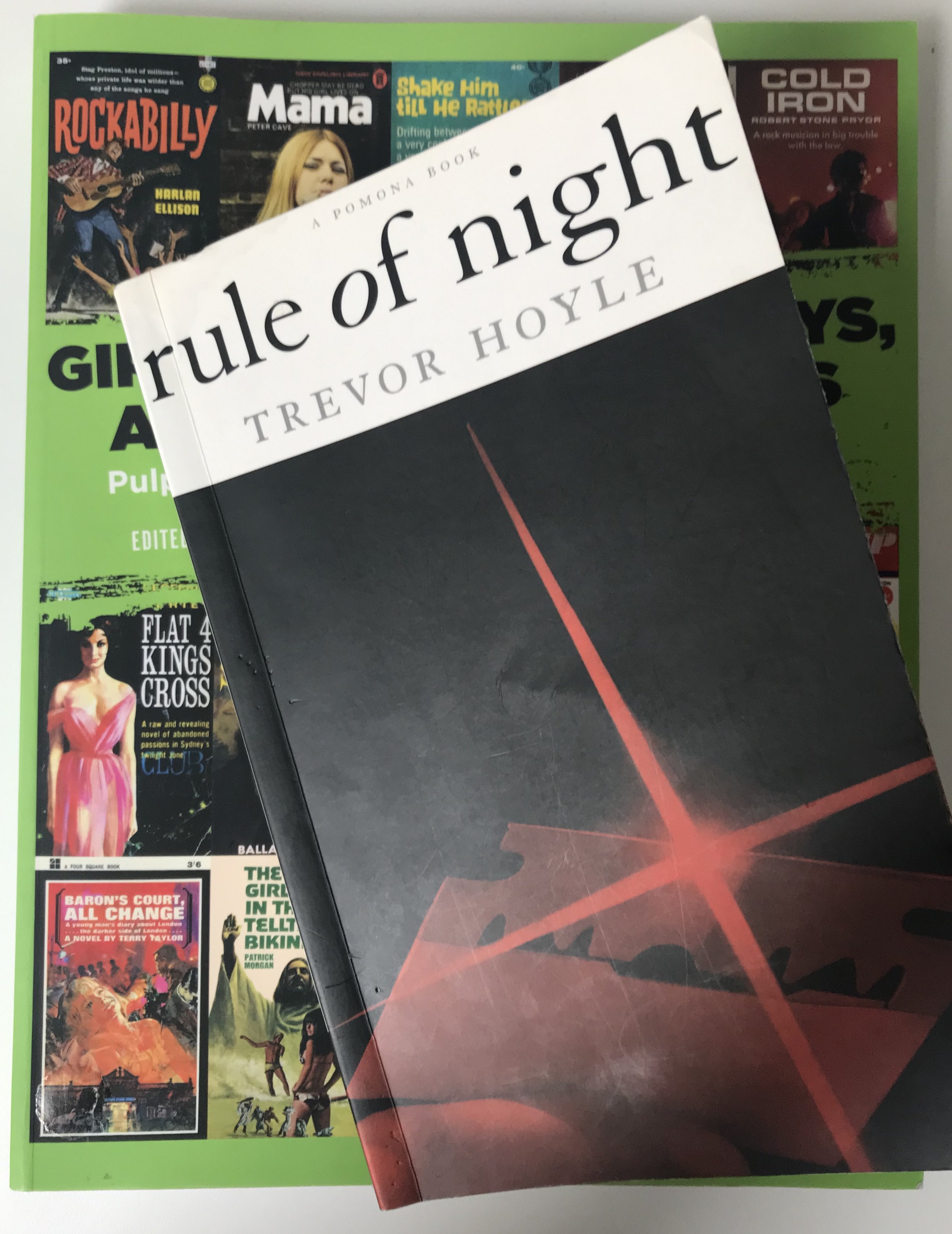

Despite being republished in 2003, Hoyle’s novel about a Rochdale bovver boy is still little known and even less written about. Originally published as a pulpy paperback by Futura, and though lacking the requisite exploitation imagery used by NEL on their Skinhead series, you would have thought it would have at least rated a mention in Iain McIntyre and Andrew Nette’s estimable Girl Gangs, Biker Boys, and Real Cool Cats: Pulp Fiction and Youth Culture, 1950 to 1980 (PM Press, 2017). Fact is, Rule of Night is anything but an exploitation title. It is by far the most convincing portrait of disaffected youth I have read; its depiction of working-class school leavers who lurch from one unskilled job to another is nuanced and subtle. Hoyle plots their endless drift around the town and excursions to Manchester and Luton, watching them getting drunk and blocked between the chance encounters that give vent, in spasms of gratuitous violence, to their balled-up anger.

Girl Gangs, Biker Boys, and Real Cool Cats: Pulp Fiction and Youth Culture, 1950 to 1980

The central character, Kenny owes nothing whatsoever to the romantic renderings of teen life essayed in S. E. Hinton or J. D. Salinger novels, and Hoyle shows little interest in the pop sociology approach taken by the authors of Amboy Dukes or Blackboard Jungle. Rule of the Night is devoid of sentimentality, Hoyle never patronises, nor sensationalises, he doesn’t explain motives; he just shows how it is. His teenagers are barely formed, grasping for a maturity that constantly outflanks them, and so search for it in beer, fags, obscenity strewn language and violence:

He says sneeringly into the face of the man, ‘Did you get a good look or do you want a photograph?’ And then says, ‘Cunt’, and goes on repeating, Cunt. Cunt.’

Fucking Jesus, he wants to hit the man. Fucking Cunting Christ, the man’s pale frightened face sickens him so much that nothing would feel better than kneeing him in the bollocks and seeing that awful fear he loves and despises turn into pain.

And that search for maturity is also there in the kids’ desperate longing:

Skush is the quiet one; he drinks his pint slow and calm and waits for the others to make up their minds. He’s never been out with a girl, never had it . . . and now wonders if it’s possible to get his end away without the acute pain and torture of having to approach a girl, talk to her, make easy conversation while all the time his lips are numb and his throat squeezed tight and dry.

Beyond the rich and varied characterisation, Hoyle makes a number of sharp observations on youth cultures; a small gang of Bury yobbos dressed as figures from Clockwork Orange infiltrate a Rochdale v Blackburn game; away from the terraces greasers and bike boys take their turn to fight with Kenny and his gang. On a trip into Manchester to sell stolen prescription drugs they encounter a motley crew of Teds at the Bier Keller on Charlotte Street, behind the Piccadilly Plaza Hotel:

Down the green steps and into the dark smoky warmth where the Teds are gathered in sullen groups listening to Gene Vincent and Fats Domino and Elvis. . . The three lads don’t respond to this kind of music: to them it seems crude and obvious . . . But there’s a market and a good sale to be had here for blues and black bombers; the Teds won’t touch acid or grass but rely on lager and pills to give them a charge.

A page earlier they are trying to off load their pills at a northern soul night. The momentarily empty dance space is described as ‘a sacred patch of territory which can only be invaded when the time and circumstances are judged right . . :

Almost precisely on the stroke of nine, a boy with short back and sides and dressed in an open-necked shirt, blue and yellow striped pullover, a pair of baggy trousers with turn-ups, and brown leather shoes with hard soles begins to dance alone . . . looking down at his feet, intent on the movements and rhythms, as though what comes next is as much a surprise to him as to the people watching.

That image of the lad in a state of surprise is unsurpassed in writings on northern soul dancing.

Girl Gangs, Biker Boys, and Real Cool Cats: Pulp Fiction and Youth Culture, 1950 to 1980