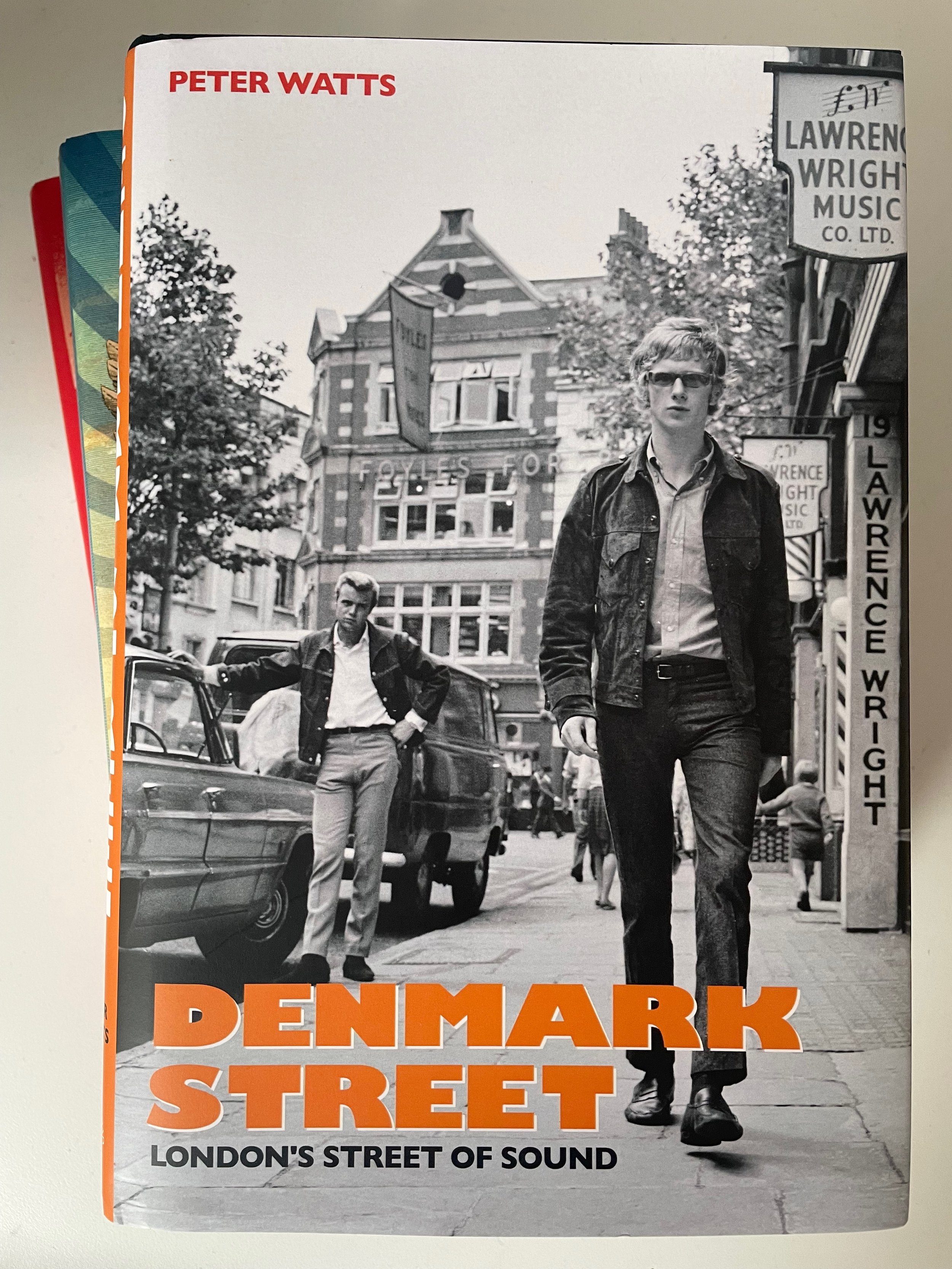

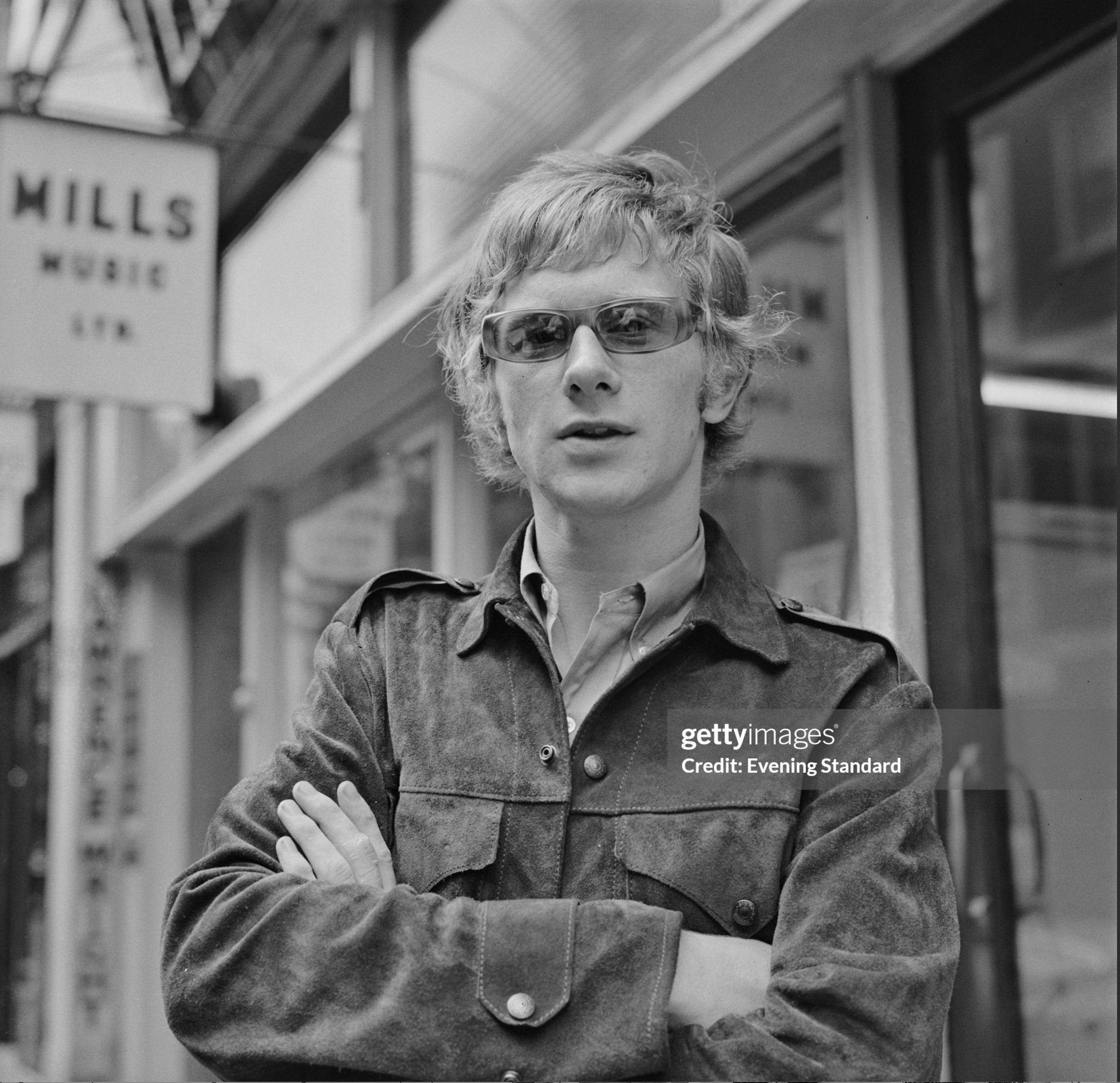

Never mind that the subject fascinates, I’d have bought Peter Watts’ Denmark Street: London’s Street of Sound for its jacket alone, which pictures Andrew Loog Oldham, August 1964, whippet short and skinny, striding past Lawrence Wright music publishers. He’s wearing a suede Levi’s-style jacket, trademark shades, open necked button-down collar shirt and trousers that are hemmed an inch or so above his shoes. Like his hero Lawrence Harvey in Expresso Bongo, Oldham has that caffeinated presence that suggests he owns these streets, if only in that moment. Behind him, across Charing Cross Road, is Foyles book shop. Between the spaces he is marking out, to his right, looking on, is a young guy with a Glen Campbell/Wrecking Crew casual style – blonde quiff, suede Cuban heeled boots, tan pants, white shirt, denim jacket – leaning on a big American car with a crushed rear fender – has US culture ever emerged unmarked from its contact with a British reality? American pop, the photograph suggests, corrupted by a youthful English swagger, is going to turn London Town upside down. Change is coming.

Peter Watts deftly (and very eloquently) maps the transformations that have taken place on this street from the Great Plague to Crossrail, from the Great Beer Flood to the virtual reality of the Outernet. The revolutions wrought by Oldham, the Stones and The Beatles are the pivot around which he works his story; detailing the shift from sellers of sheet music for vocal with piano accompaniment to publishers of music composed, performed and recorded by the artistes themselves.

Until the recent demolitions and building projects, in my imaginary, Denmark Street was unchanged and unchangeable, it had always fallen beneath the shadow of Centre Point, guitars were always its main business and I would always move through it without care or thought, passing quickly on my way to Wardour Street or wherever. Watts causes a pause in this mindless flow so as to take stock of the street’s fabled history, to move off the pavement and into its buildings, to meet the people who worked and lived there, to follow the traces its businesses have left behind; the commerce undertaken in pursuit of fortune small and large.

Whether the exchanges parlayed were legitimate or illegitimate, selling sex or selling a tune, it all lacked even a thin veneer of bourgeois respectability. With the new developments it is not just the loss of some of the buildings that creates a nostalgia for the place, it is rather the street’s regulation and ordering of permissible activities. I don’t feel a great need for the Sex Pistols’ first rehearsal space to be saved from gentrification, that matters to me as much as a blue disc on the house in Edith Grove to mark where the Stones once lived, nor do I mourn the closing of the 12 Bar Club any more than I do the Marquee, but I do feel the absence of another central London space where, whether fuelled by nefarious business practices or more romantically inclined sensibilities, temporary creative alliances might spark into life and infuse a new generation’s imaginations. Watts’ marvellous history of a small street in London has made me feel that loss more keenly than any other. But yeah, you also need to know about the Great Beer Flood of 1814 . . . that event deserves a plaque.

With its new addition of Denmark Street to sit alongside Robert Sellers’ Marquee: The Story of the World’s Greatest Music Venue and Andrew Humphreys’ Raving Upon Thames, Paradise Road is fast becoming my favourite publisher, all are beautiful presented, generously illustrated and with stories to tell. Get some!