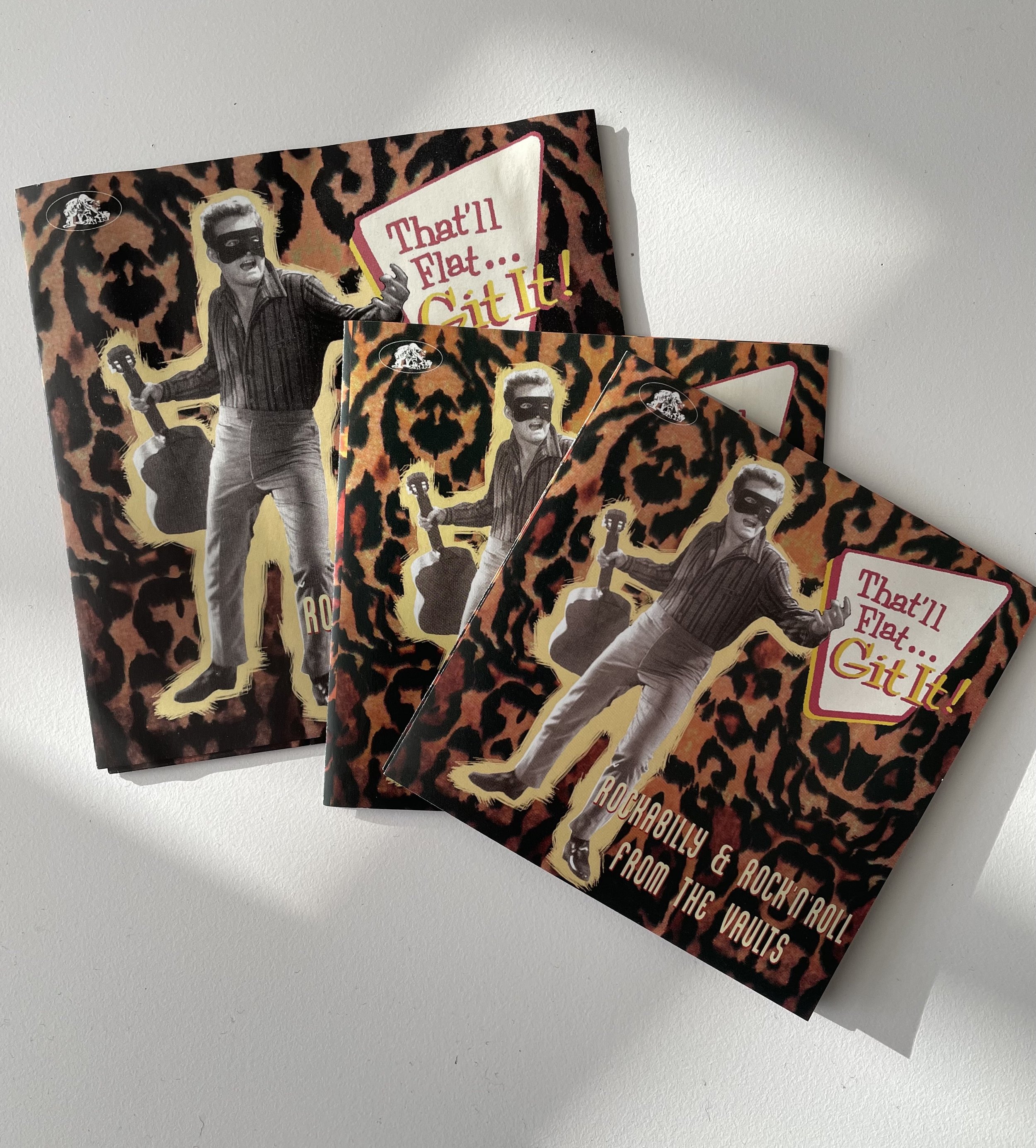

Bear Family have just issued volume 46 in their rockabilly series That’ll Flat . . . Git It! that began waybackwhen in 1992. I don’t pretend to listen to each new volume with the same ardent fervour as I did thirty years ago, but my admiration for the compilers’ dedication to the task of cataloguing and archiving this small corner of popular music knows no bounds. . . I’d buy each release for the photos and sleeve notes alone. Whenever the task is done, if that is ever likely or even possible, I hope they put all the text and images together in one giant hardback book

The series is the digital version of the rockabilly by label compilations that were released from the mid 1970s to early 1980s that were curated by Rob Finnis, Bill Millar, Colin Escott, Stuart Colman and the like. It was then a very British obsession. Some 20 plus albums were released, which apart from the then ongoing excavations in the Sun vaults must have seemed pretty exhaustive. Yet, here go Bear Family barrelling on with near 50 silver discs in their catalogue.

Volume 46 is dedicated to Chess and affliate releases, it is the second one to feature the label. 64 tracks in all. In their notes for the original vinyl release Finnis and Millar considered its 20 tracks to be ‘virtually the sum total of the Chess brothers erratic forays into rockabilly’. Perhaps their view of the form was stricter than those who came after, certainly Bear Family, with volume 27, expanded their scope by adding “rock ‘n’ roll” to ‘rockabilly from the vaults’ which meant they could include Chuck Berry and Big Al Downing on their latest release. That’s no hardship to endure (and better than some of the more uptempo country numbers that have helped swell out the track listing in other volumes in the set).

Anyway, this one on v.46 gets my stamp of approval. Tell us about your baby Steve . . .