It’s 1957, just a few pages into Anthony Scaduto’s Bob Dylan biography and the author is introducing his reader to Dylan’s high school girlfriend, Echo Helstrom. She’s 15 years-old and Bob has yet to make any impression on her. He’s a ‘clean-cut goody-goody kid’ who lives over the tracks from Echo in the well-to-do side of town. Their paths cross at the drug store where he has been playing upstairs at the Moose Lodge. Echo told it this way:

He walked in with another boy, John Buckland, and they came over and started talking to us. Picking us up, I guess. I think I had on my motorcycle jacket and a pair of jeans. Very uncouth, for Hibbing.

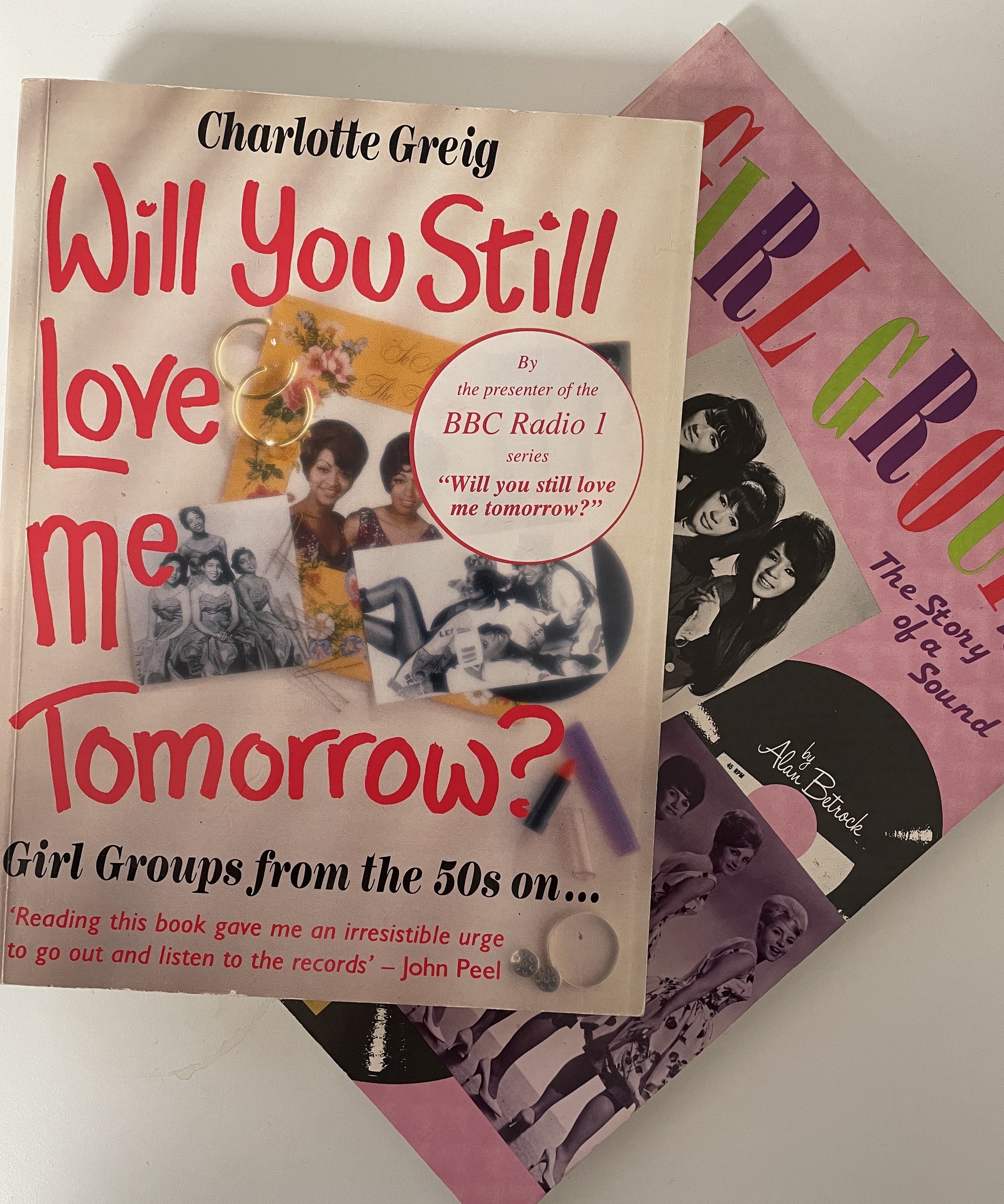

Predating The Crystal’s ‘He’s A Rebel’, The Shangri-las’ bad-boy melodramas, Janis Ian’s ‘Society’s Child’ and a thousand other teen operas, the story told by Echo flips the bad-boy trope and puts the girl in denim and leather and from the wrong part of town. Echo and Bob bond over their shared enthusiasm for the Blues and tear-up the town on his motorcycle. Before he’d graduated, the trope had turned back and the other girls in school look with nervous desire at Bobby Zimmerman, the nice boy turned hoodlum in his ‘big boots and tight pants’. He’s good-bad but he’s not evil.

In Chronicles, Dylan recalled of Echo that ‘Everybody said she looked like Brigitte Bardot, and she did’.

Postscript:

In Toby Thompson’s Positively Main Street: an unorthodox view of Bob Dylan (1972) his ‘gushing' pseudo-new journalistic account has Echo Helstrom at the centre of the story of Dylan and his Hibbing roots. He paints Echo, ten-years or so older, as a free hippie spirit, twisting and twirling away from a conventional image of the small town, High School, girlfriend. She recalls riding behind Dylan on his m’cycle and killing time together drinking sodas but the image of her as a Brill Building fantasy figure, teen-age delinquent, is choked off:

The drone of Muzak could be heard from another room.

“You hear that song!” – Echo shuddered – “the one they’re playing over the speakers? Do you recognise it?”

I listened for a moment and had to confess that I didn’t. It was standard, mid-fifties, C, A-Minor, F, G-Seventh arrangement, I knew that much.

“It’s ‘Angel Baby’, Echo moaned. “Bob used to call me that . . . Angel Baby, I mean.”

“For Christ’s sake”, I said, “Come on, I’m taking you home.”

Echo should have told her story to Nik Cohn, he’d have known both the song and where she was coming from . . . as Dylan would’ve

He don't comb his hair

Like he did before

And he don't wear those dirty old black boots no moreHe used to act bad

Used to, but he quit it

It make me so sad

'Cause I know that he did it for me

Shangri-Las ‘Out in the Streets’