A fascinating interview with James McMullan who provided the sharply observed illustrations that accompanied Cohn’s story is found here

London Rock 'n' Roll Show, Wembley 1972

Paul Gorman has posted a host of images and information on the show, here. Dig around a little more on his site and you’ll find much much more on the topic, especially on the Malcolm McLaren connection

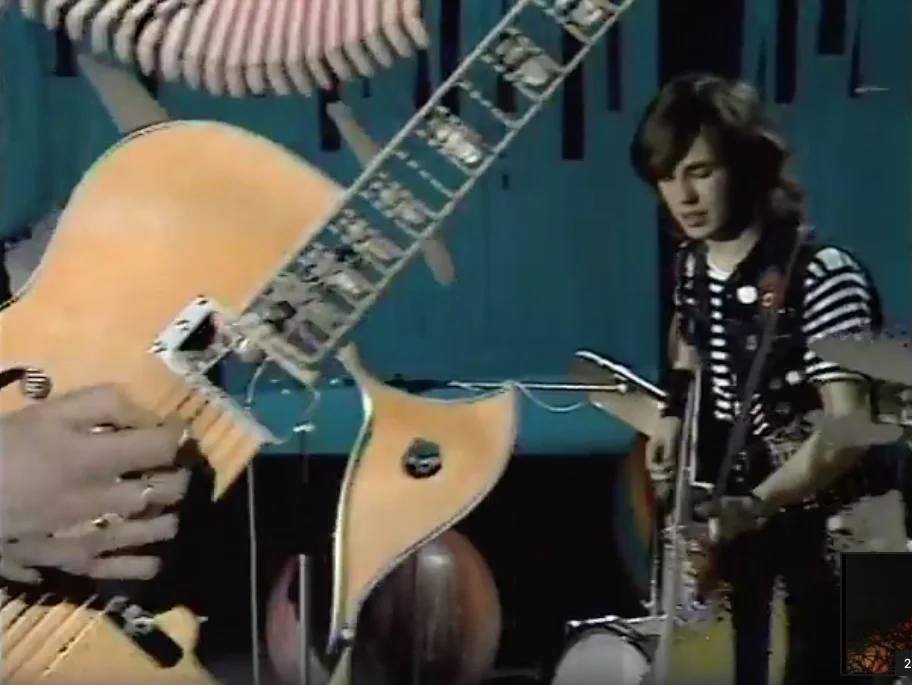

Wild Angels - 'Brand New Cadillac' 1973

For this performance alone, the Wild Angels fully justify the early seventies R’n’R revival . . . Vince Taylor’s number also opens their superior Decca album Out at Last (1973), which is, with Shakin’ Stevens and the Sunsets’ Legend (1972), the best recordings the revival had to offer.

London Rock and Roll Show 1972

Looking toward the future and the MC5’s set, Wilko Johnston backs up Heinz on an excruciatingly bad cover of Cochran’s ‘C’Mon Everybody’ at the 1972 London Rock and Roll Show at Wembley.

The BFI really should release a hi-definition disc of this doc . . . band performances are uniformly horrible, all the energy and interest is in and with the audience.

Born Losers

Whatever the outlaw biker picture, whether in bikinis or not, small town girls are always a willing audience for the hoodlums’ pranks

Elmore Leonard and The Tall T (part 2)

LaBrava (1983) begins Elmore Leonard’s evermore excessive referencing of Hollywood movies and the use of narrative devices that depend on a merging of the real and the reel that had its greatest success with Get Shorty (1991). Here, a middle-aged retired Hollywood star who specialised in femme fatales replays one of her old movies . . . Robert Mitchum is endlessly referred to, but it is talk of Henry Silva who jogs another movie memory:

“I know Henry Silva was the bad guy,” LaBrava said. “I remember him because he was in a Western just about the same time and I saw it again in Independence. The Tall T, with Richard Boone and, what’s his name, Randolph Scott.”

Elmore Leonard and Valdez is Coming

Elmore Leonard’s in-jokes #1

“You’re positive,” Raylan said, “it was Bob Valdez.” …

“Before they showed,” Loretta said, “Bob phoned and said to tell my dad, ‘Valdez is coming.’ You ever hear of anything like that?”

Elmore Leonard Raylan (2012). Valdez was first published in 1970

'The Tall T' - by his bandana you will know the man

The Tall T (Budd Boetticher, 1957)

By his bandana a man will be judged …

Chink’s and Billy Jack’s flamboyant bandanas are contrasted with Pat Brennan’s (Randolph Scott) more sedate affair, but all pale next to Frank Usher’s (Richard Boone) turquoise neckerchief.

Playing on the period’s usual Freudian overloading, Chink (Henry Silva) and Billy Jack (Skip Homeier) are perfectly drawn punk psychos – fully formed killers but barely formed humans.

Boone is wearing a corduroy Wrangler 11MJ style jacket - pure 1950s – Homeier wears Levi’s under his leather chaps …

Elmore Leonard and The Tall T (part 2)

This map was produced for The Complete Western Stories of Elmore Leonard, most of the tales take place in Arizona. It got me to wondering whether the map would also double for the territory Budd Boetticher’s characters wander through …

Elmore Leonard and Stag O'Lee (part 2)

Elmore Leonard and The Tall T

Jack Ryan and the half child, half woman, all bitch Phyllis Dietrichson character are stalking around a house when he recognises a Western that is playing on the TV …

Elmore Leonard and George V. Higgins

Final Episode of Justified

Watching Justified as each new season appeared like an evermore welcome spring I’d forgotten that Higgins’ novel had been used earlier by Raylan to explain things to some low-life, so when the book got bandied about in the final episode I thought it was some more or less random Tarantino-esque homage. But Stray Bullets blogspot has persuaded me it was anything but:

The Friends of Eddie Coyle had long been cited by Leonard as the book that inspired him to stop writing westerns and to try his hand at crime fiction. It was a book that changed his life.

In 2000, Leonard wrote: “What I learned from George Higgins was to relax, not be so rigid in trying to make the prose sound like writing, to be more aware of the rhythms of coarse speech and the use of obscenities. Most of all … hook the reader right away.”

Leonard had also said of Higgins: "He saw himself as the Charles Dickens of crime in Boston instead of a crime writer. He just understood the human condition and he understood it most vividly in the language and actions among low lives.”

Raylan closes the book and gives it to Tim. As with so much of Leonard, it’s an understated, almost disposable gesture freighted with unspoken emotion. It’s heartfelt, but neither Raylan or Tim act like it means much of anything at all. It's just a beat-up old paperback, right?

As Raylan walks out of the office forever, in the background, (quite literally behind his back) Tim is approached by office irritant Nelson.

Nelson: You gonna read that book, Tim?

Tim: No, Nelson, I’m gonna eat it.

Nelson: I read fast. Have it back to you tomorrow.

Tim: Keep talking, I’m gonna throw this stapler at you.

The tagline on the movie poster for the Peter Yates adaption of The Friends of Eddie Coyle could equally apply to Justified if you substitute the word "Eddie" for "Raylan": “It’s a grubby, violent, dangerous world. But it’s the only world they know. And they’re the only friends Eddie has.”

Elmore Leonard and Gloria Grahame: 'Up In Honey's Room' (2007)

The designer of Leonard’s hardback edition of Up In Honey’s Room didn’t have to do too much work after locating this image of Gloria Grahame in Nick Ray’s A Woman’s Secret (1949); even the Lugar is in keeping with a scene or two in the book …

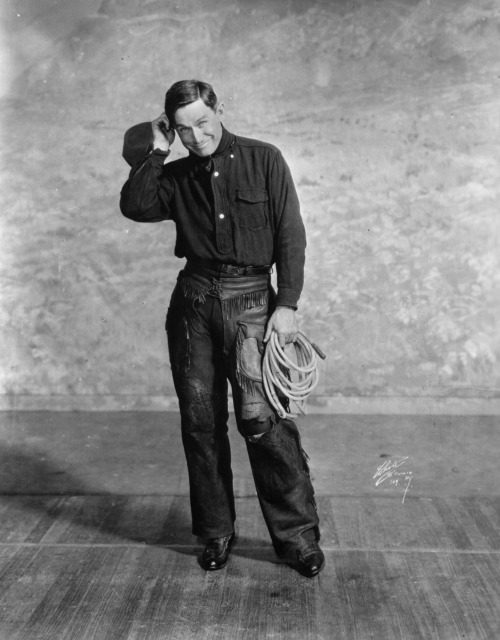

Elmore Leonard and Will Rogers

… this federal lawman from Oklahoma who believed Will Rogers was the greatest American who ever lived because there wasn’t anyone as American as Will Rogers. He was funny and dead-on accurate when he took shots at the government, and he was always a cowboy. Carl said, “You could tell he was the real thing by the hundred-foot reata he carried around, could do tricks with, throwing his loop over whatever you pointed to and never had to untangle it. Jurgen was thinking that if he ever saw Carl Webster again, even if Carl had him handcuffed, he’d ask him how one became a cowboy.

Elmore Leonard, Up in Honey’s Room (2007)

Elmore Leonard and Stag O'Lee (part 1)

Jimmy Cap said “You don’t take your cowboy hat off in the house?”

Raylan said, “Being in your house has nothing to do with it. My hat stays on ‘cause I won’t take it off to you or anybody like you.”

Elmore Leonard, Pronto (1993)

Warren Oates and Elmore Leonard

Elmore Leonard Stick (1983)

Recently released from prison after a seven-year stretch, Stick is finding it hard to comprehend some of the changes that have taken place.

Stick thought he had kept up … But maybe he had missed a few important events and passings. Nobody had told him when Warren Oates died last spring. He had heard about Belushi but not Warren Oates.

Stick’s judgements on those he meets are often measured by how well they stack up against his favorite actor:

Stick looked at the mirror, at the young millionaire trying to sound street …The street tone didn’t go with the words. Guy didn’t know how to stay in character… Trying to sound on the muscle now, a hard-nose. The guy should try for the movies. See if in about a hundred years he could take Warren Oates’s place.

Against Warren everyone comes out looking like a phoney, when someone suggests CHiPs star Erik Estrada should be cast in a cop movie, his response is predictable:

Jesus Christ, Stick thought. Warren Oates dead, you bonehead, could play it better than Erik Estrada.

The novel is among Leonard’s best and has a nice bit of business about earning respect and crushed cowboy hats, which Stag O’Lee chroniclers should enjoy …

The Hitch-Hiker (Ida Lupino, 1953)

In Kino Lorber’s blu-ray of the Library of Congress’ print of The Hitch-Hiker, when not swaddled in a blanket, Frank Lovejoy’s character sports washed-out Wrangler pants and Levi’s 506XX (Type 1)

. . . weird thing is the jacket has a seam down the back and the shoulders drop down to his elbows. Not seen that before.

Perhaps the costume dept took some scissors to the outfit?

Whatever, it’s a terrific thriller, though Lovejoy and Edmond O’Brien’s characters are ridiculously passive throughout. Why one of them didn’t clock William Tallman’s one-eyed psychopath 15 minutes into the film is anyone’s guess. The deeper they go into Mexico the more time they seem to spend on Lone Pine’s dirt roads. The landscape is unchanging.

The Competition: Pulp Who

Connor McKnight & Caroline Silver, The Who Through Pete Townshend’s Eyes (Scholastic Book Services, 1974)

George Tremlett, The Who (Futura (1975)

Brian Ashley & Steve Monnery, Whose Who? A Who Retrospective (NEL, 1978)

John Swenson, The Who: Britain’s Greatest Rock Group (Star, 1979)

These four exploitation titles show what can be achieved with a press file, a box of clippings and a typewriter. Standardised, interchangeable and written to be consumed in one sitting, even the photographic inserts appear like TV show repeats: same time, same channel, same thing. 1970s pop biographies were the equivalent of the movie paperback tie-in - adaptations of original scripts - designed to milk a film’s popularity and then to be quickly forgotten. Pure pop artefacts . . .

Brexit's Little Englanders - ain't nothing new under the Empire's sun

“I don’t understand my own country any more,” I said to her. “In the history books, they tell us the English race has spread itself all over the dam world: gone and settled everywhere, and that’s one of the great, splendid English things. No one invited us, and we didn’t ask anyone’s permission, I suppose. Yet when a few hundred thousand come and settle among our fifty millions, we just can’t take it.”

Colin MacInnes, Absolute Beginners (1959)

Welcome to Fear City

Nathan Holmes, Welcome to Fear City: Crime Film, Crisis, and the Urban Imagination

(Albany: SUNY Press, 2018)

During the Summer of 1975, in order to manage New York’s budget problems, Mayor Beame openly discussed the possibility of discharging significant numbers of uniformed police officers and firefighters. Public sector unions hit back by publishing a pamphlet, ‘A Survival Guide for Visitors to the City of New York’, to be handed out at transit terminals and at subway entrances. On the front of the pamphlet, beneath the legend ‘WELCOME TO FEAR CITY’, a skull with a cracked-toothed smile, encircled by a cowl, fills the page. Inside, travellers are provided with guidelines to better ‘enjoy’ their ‘visit to the City of New York in comfort and safety. . . Good luck.’

The guidelines warn the unwary to ‘stay off the streets after 6 pm’, when even in midtown ‘muggings and occasional murders are on the increase during the early evening hours.’ If you must leave your hotel after 6pm, ‘Do not walk’, summon a radio taxi, ‘avoid public transportation’: ‘Subway crime is so high that the City recently had to close off the rear half of each train in the evening so that the passengers could huddle together and be better protected.’ And on it went, ‘remain in Manhattan’, ‘Protect your property’, ‘Safeguard your handbag’ . . .’Be aware of fire hazards.’ For any habitual filmgoer, by 1975 such scare tactics would have appeared second-hand at best.

Movies such as Klute (1971), The French Connection (1971), Serpico (1973), Detroit 9000 (1973), The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (1974), and Death Wish (1974) had all confirmed an image of New York as broken-backed, politically and socially, and rotten with criminal activity. The same was true of other major American cities, which were repeatedly rendered in the media as sites of violent disorder, social crisis and urban blight. Taking his book’s title from the pamphlet, Nathan Holmes builds his study of crime film and the urban imagination on case studies of these six movies, while pulling in numerous other titles that sit comfortably within the 1970s cycle of gritty thrillers.

Other film scholars have worked this territory before Holmes, most notably Stanley Corkin with Starring New York: Filming The Grime and Glamour of the Long 1970s (2011), but Welcome to Fear City moves beyond film analysis and symptomatic readings to investigate a more compelling, because exacting, range of contexts. Film’s topicality, the way movies respond to and take part in the debates and discourses of their time, are of prime concern. The public sphere is opened up for analysis through a study of the figure of the Super Cop, exemplified by The French Connection and Serpico. That chapter works with a range of transmedia manifestations, especially magazine coverage as found in contemporary articles and photo spreads in New York and Life. Architectural spaces that relate to Klute, predominantly parking garage, apartment, discotheque and skyscraper are explored in the book’s opening chapter.

Leaving New York momentarily behind for the Midwest, and exploring the Motorcity’s reputation as the nation’s murder capital, Holmes considers the cycle of Blaxploitation films, marketing ballyhoo and scenes of street walking in a chapter that takes the little known exploitation movie Detroit 9000 as its focus. With Pelham and Death Wish the ‘bystander effect’ forms the hub of his inquiry. The moral panic about crime and public indifference was woven out of the 1964 media coverage of the murder of Kitty Genovese. Her killing was said to have been witnessed by neighbors, who chose not to get involved. A number of films and television programs were made that used the story either directly or indirectly, but none with greater box office success than Michael Winner’s film, Death Wish.

These are the core topics of each chapter that are drawn together within the wider context of film and modernity, a field developed by scholars at the University of Chicago, such as Tom Gunning and Miriam Hanson, who are more than ably supported in their studies by the likes of Ben Singer and Edward Dimendberg. In turn, all these scholars draw on the work of the Frankfurt School, especially the theories of Walter Benjamin and Siegfried Kracauer. While the guidance and influence of the Germans and their American followers is readily apparent in the framing of each chapter, it is to Holmes’ credit that he uses their theories with a light enough touch so as not to obscure the actual object of his investigation, the films, their times and the cities they represent:

In the socially homogenized, fortified, and consumerist cities of the present, the problem is not over-stimulation but under-stimulation. The super-cop films of the 1970s stand on the precipice of this transformation. Their white police avatars and urban tourism demonstrate an enduring interest in the city as a social location. If The French Connection rises above the rest to remain a compelling film today, however, it is because its strange energies of urban stimulation still speak to us, beckoning us around corners, down streets, and through strange passages.

Whether attending to a film’s production, marketing, exhibition or reception, or to its formal properties, Holmes shows that he is first and foremost a film scholar with clear affinities to New Cinema History. At least, in the manner in which he attends to the ‘circulation and consumption of film and examines cinema as a site of social and cultural exchange,’ a method here summarized by Richard Maltby one of the field’s leading theorists. This approach is a highlight of the book, so that, even if a film is well known to a reader, there is much here that will be entirely new.

Furthermore, the specifics of a film’s history are superbly complemented by Holmes’ wide use of architectural and urban theory, debates in city planning and politics, and in popular discourses on crime and criminology. Discussing the vogue in ‘ruin porn’ that forms the iconography of today’s imaginary Detroit, Holmes writes:

Even as Detroit became visually emblematic of urban decay, it was electronically recalibrating the soul music it had helped innovate into synthesized funk. In the globally influential music of Detroit Techno, the ballet of foot pursuit through urban blight is converted into looping rhythms that reassemble the noise-pieces of industry and the beat of the freeway into a forward-looking, unrelenting motion. For a moment in the 1970s, this same motion was captured on film and broadcast to the nation in the coded images of Detroit 9000; the first Hollywood Midwestern made in Detroit.

Elsewhere, I’ve written about the bad contract between the cinema and its patrons, between the sidewalk and the screen, where film promises to be truthful in its rendering of the social. At best, the movies provide only a weak echo of the street’s cacophonous sounds and visual sensations, but film’s lack of authenticity, its refusal just to be a recorder of reality, is compensated by the use of familiar stories, structures of narration, and spectatorial pleasures. Welcome to Fear City captures the formulaic traits of the crime film and enables us to see them anew through the prism of the historical and theoretical contexts Holmes provides. Mark my words, in Film Studies that is a feat worth celebrating and this is a book worth your trouble to read.