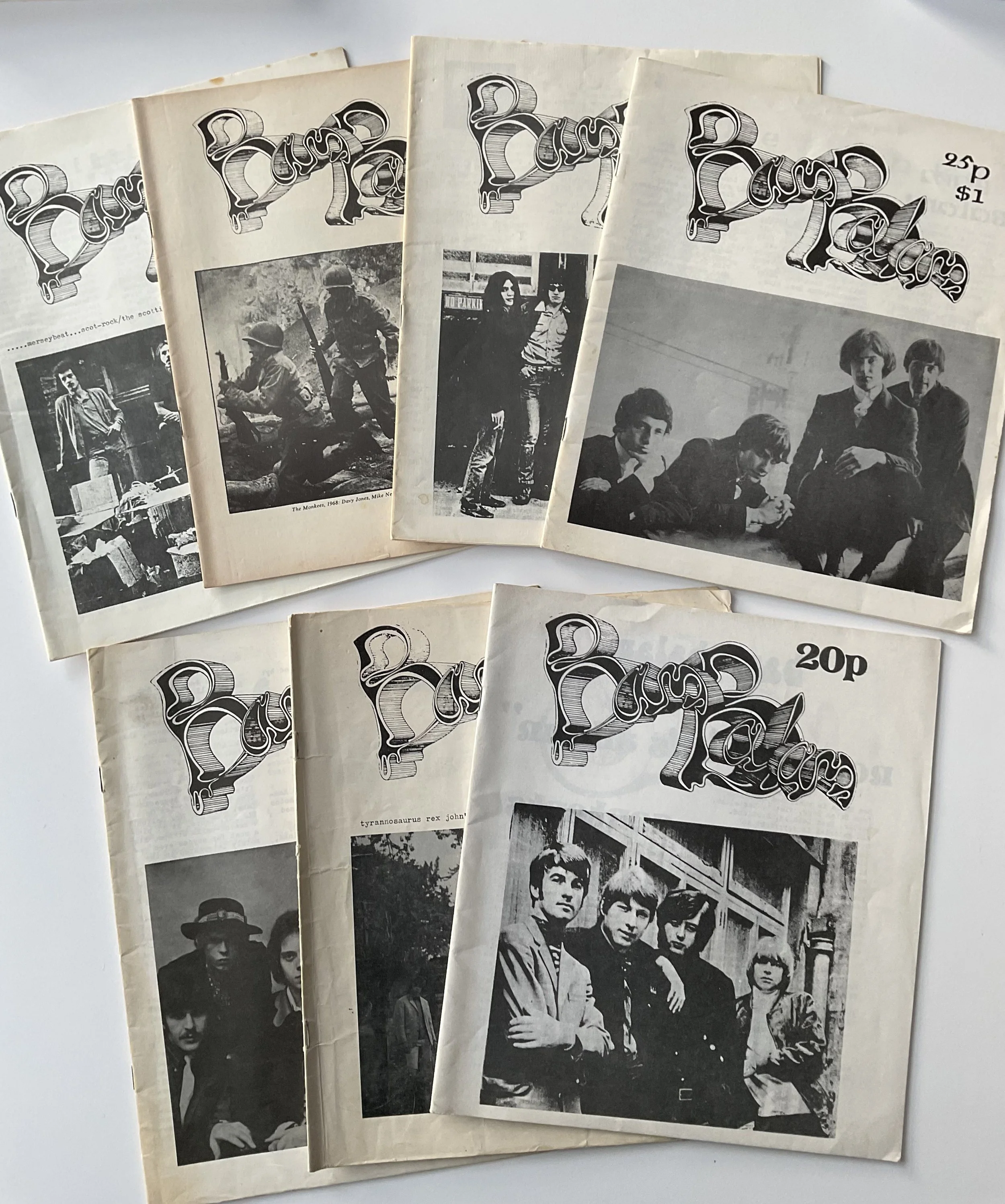

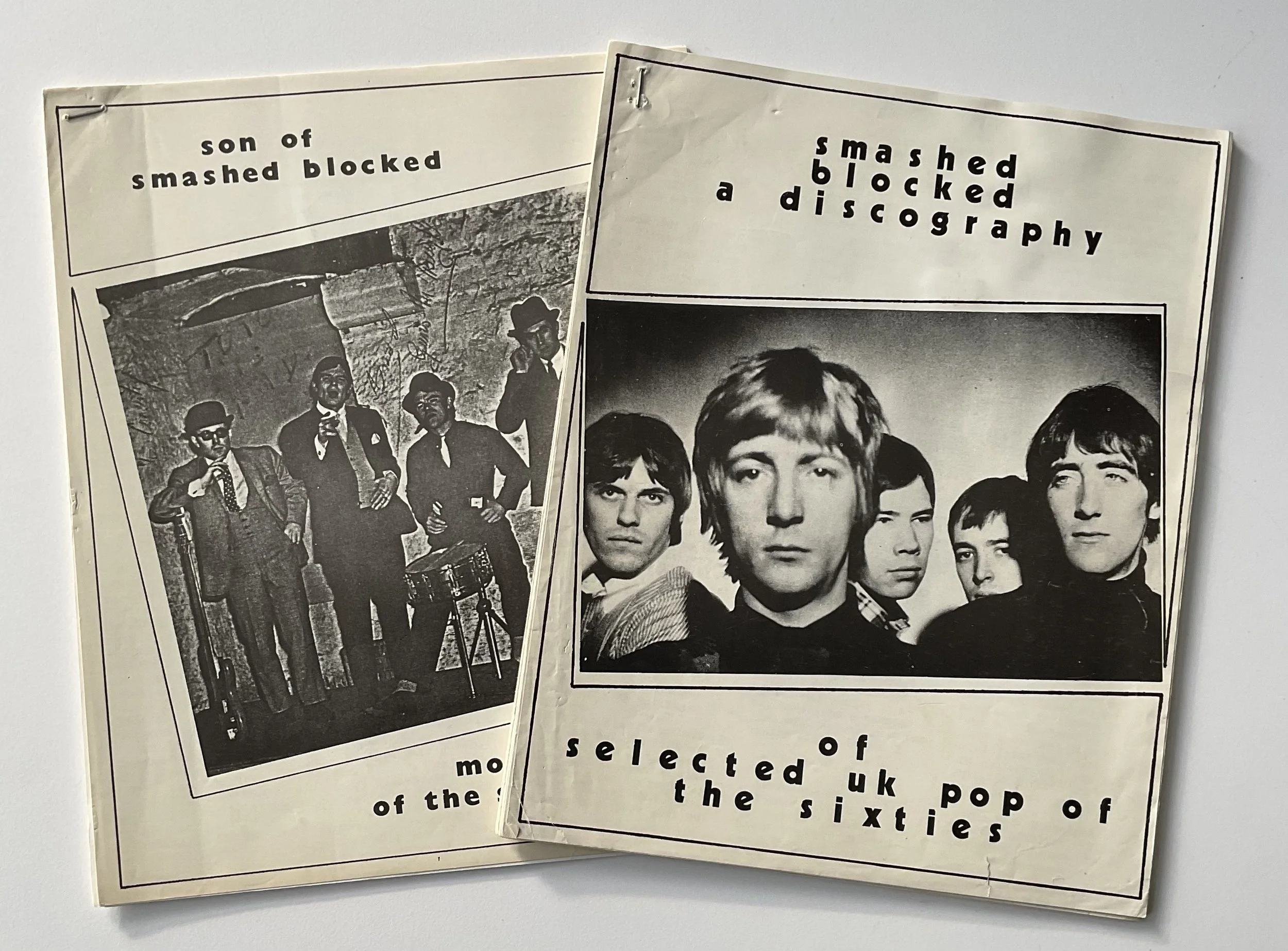

Confession time: I was a teenage Bam Balam reader. I would study the half-dozen or so copies I owned, imagining what the Eyes, the Creation, the Fairies or a 100 other pre-1968 British beat combos’ records actually sounded like. I had odd albums and a few singles by Them, Yardbirds, Who, Animals and the mighty Pretty Things, but they seemed no more than a billboard for the marvels inside the pages of Brian Hogg’s fanzine. It was not until the early 80s when the treasure trove locked away in British record company archives was finally opened, most impressively by Edsel beginning with the Creation and the Action, that I got to hear something of the forgotten legion that Bam Balam documented.

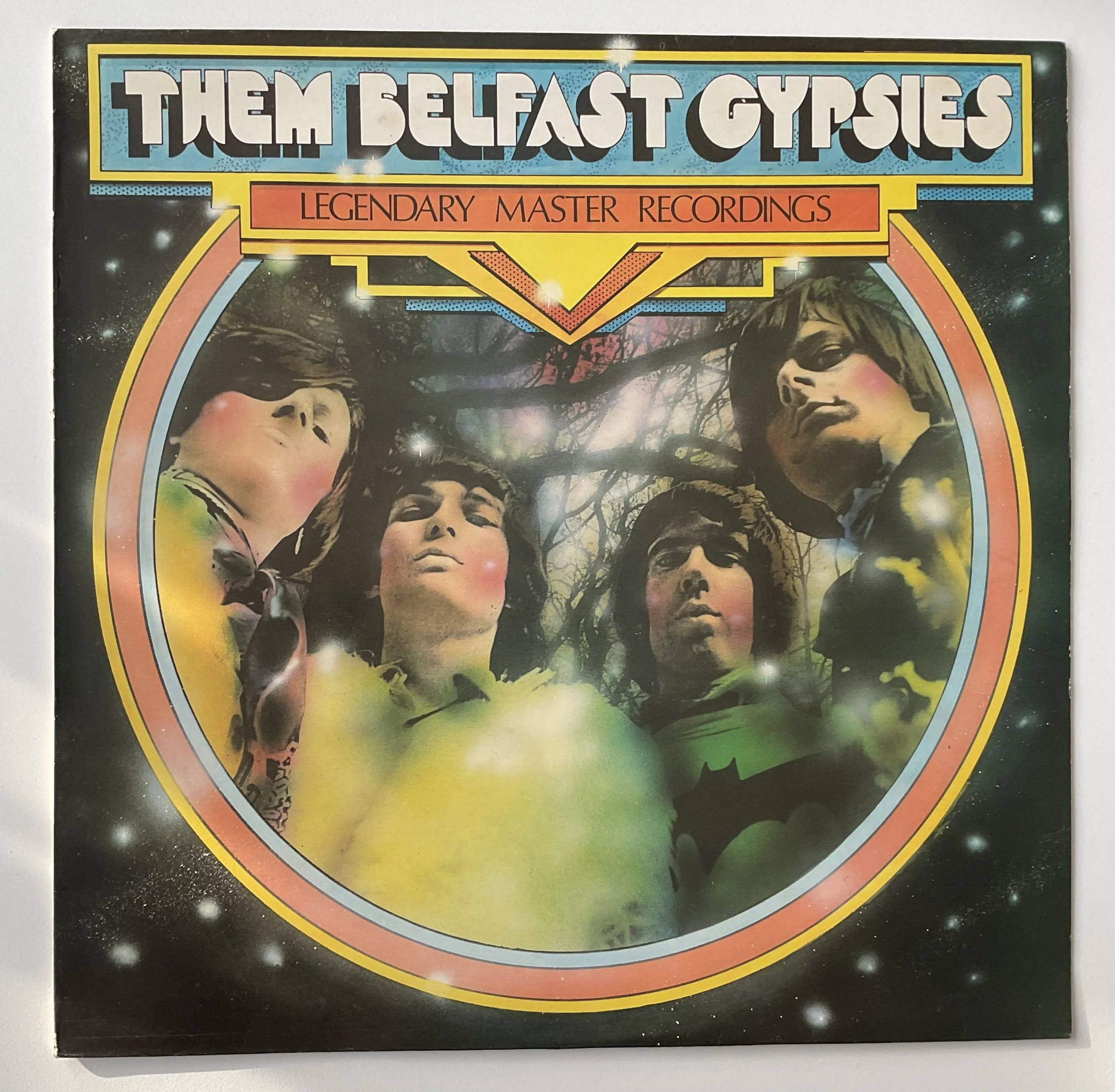

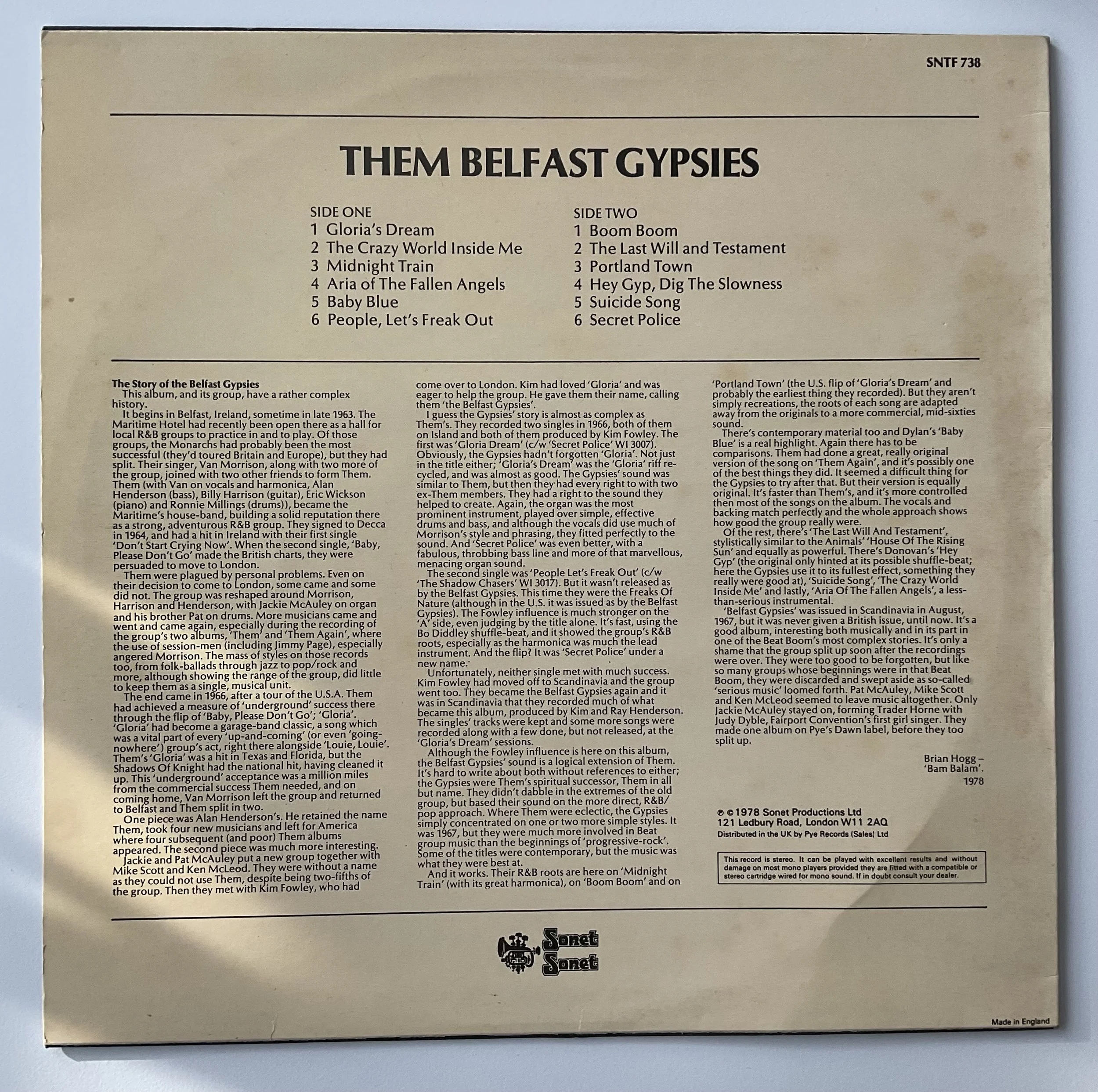

The expectations that Hogg’s fanzine had fed were fully met, his taste fully vindicated. I don’t know how many liner notes he wrote for the reissues that followed his first effort with the Belfast Gypsies but it must compete with the number of discs in Billy Childish’s discography. I don’t think it much of an exaggeration to say I took as much pleasure in what he had to say about each band as I did in the music itself; music and words a perfect complement to each other.

Alongside Bill Millar’s notes for a hundred rockabilly compilations and Mark Paytress’ for Marc Bolan’s reissues, Brian Hogg’s took a lowly irrelevant form, usually filled by complete drivel, and turned it into an art.

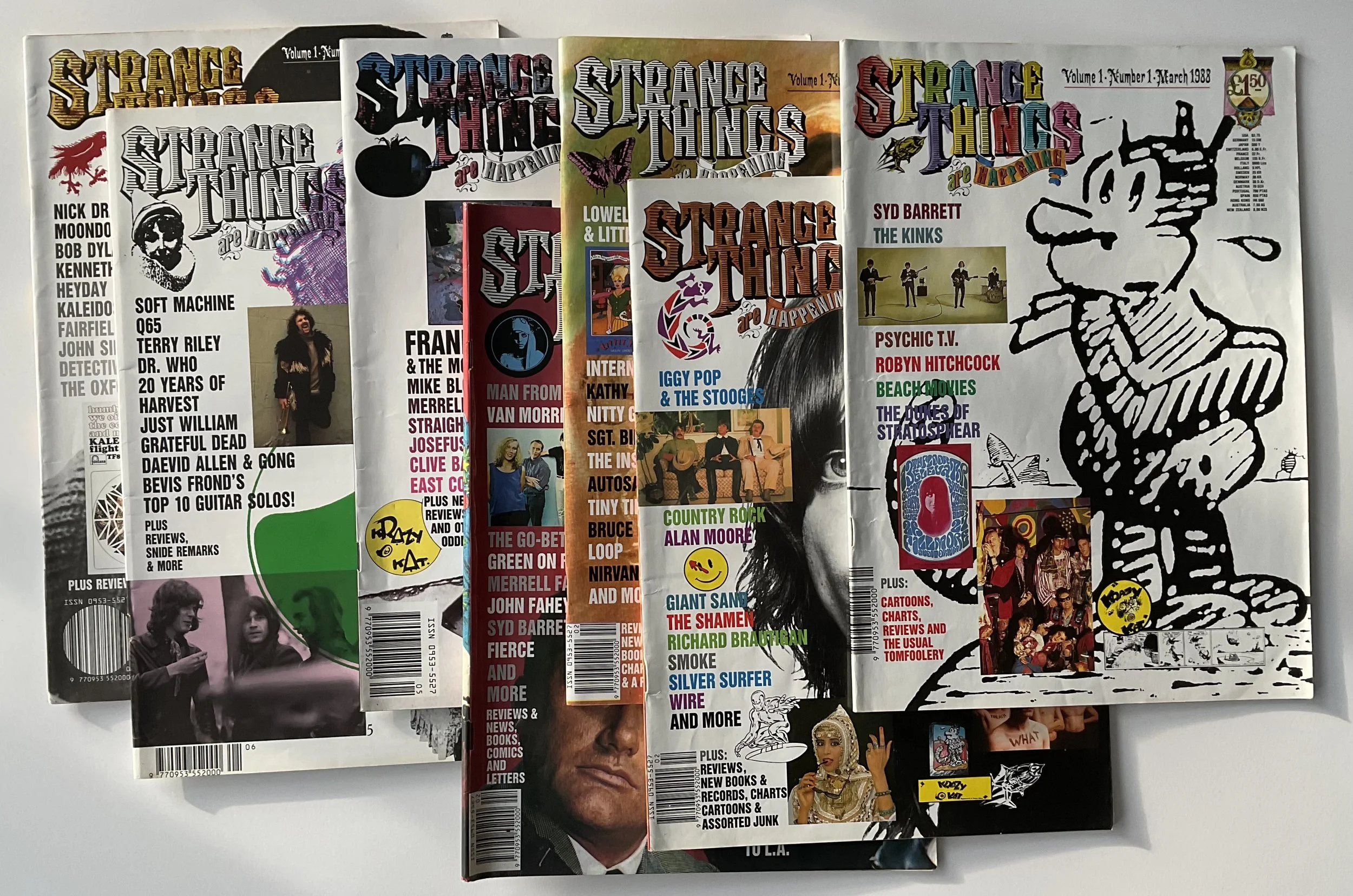

Hogg also played a full role with Strange Things are Happening magazine and subsequently published a couple of books, one a history of Scottish pop the other a history of Edinburgh’s counter culture. Not much though has been heard from him since around the turn of the century. Maybe he found other interests, other ways to occupy his time or maybe the work just dried up.

Whatever did happen he has clearly not lost his enthusiasm and love for the music he had written about and shared in the second quarter of the 20th Century, that much is certain.

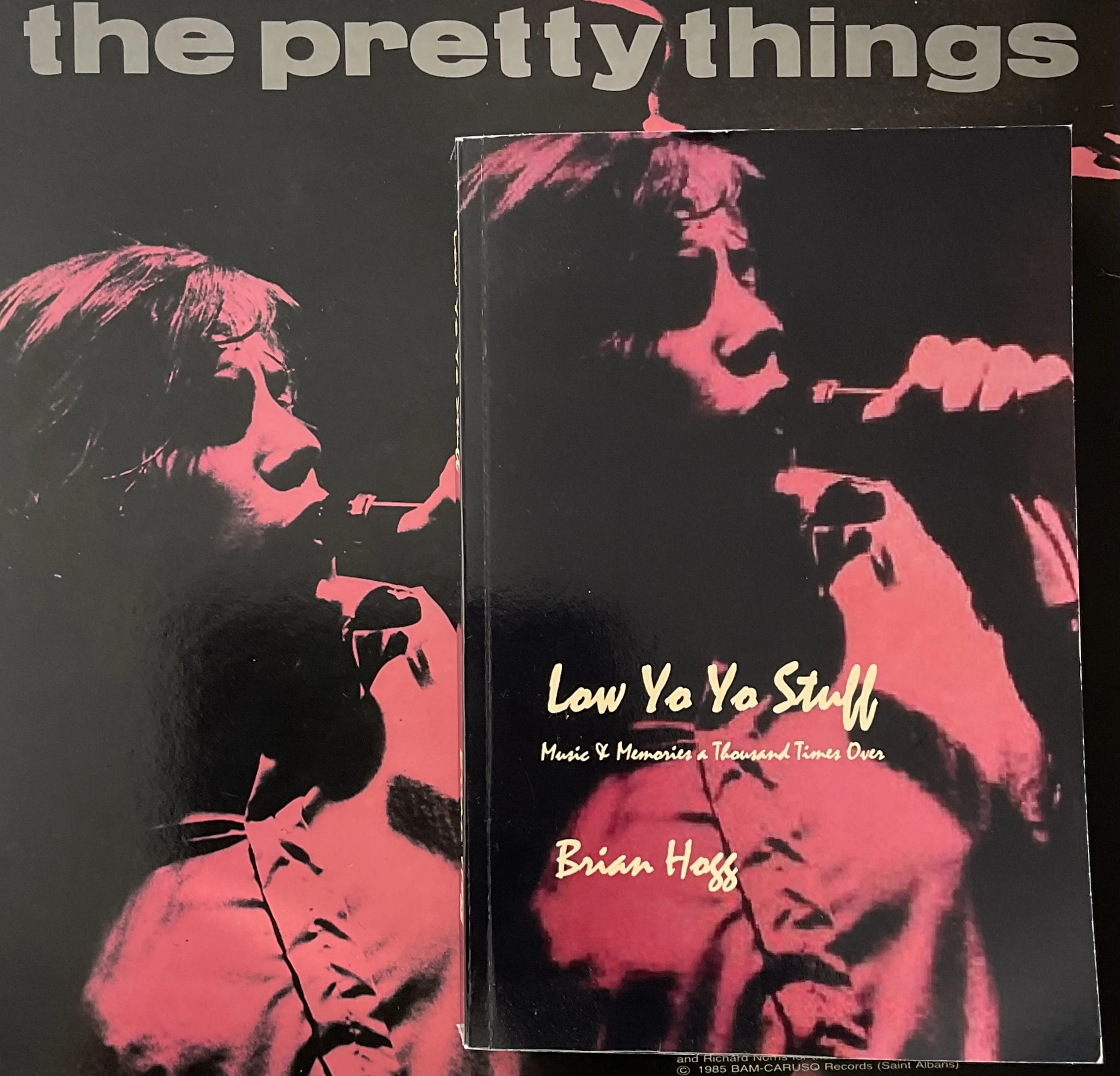

The proof of that is in his self-published, print-on-demand, volume that sneaked out toward the end of 2025 (last I looked it was only available via Amazon) – Low Yo Yo Stuff: music and Memories a Thousand Times Over.

Taking his cue from Dave Marsh’s The Heart of Rock and Soul: the 1001 Greatest Singles Ever Made (1989) Hogg repeats this marathon effort but drops the idea of his list being definitive, ‘the greatest’. Hogg’s list is more personal, more authentic, I think, while being equally fun and informative.

I don’t imagine Marsh or Hogg intend for their books to be read from front to back, rather they are designed for browsing. You just jump in to see if your favourite records have been included and what is said about them. Along the way you might pick out a random obscurity, something that might tempt a jaded palate, or something you intentionally ignored or dismissed back in the day that might be worth revisiting (if what they have written can hold your attention), but I doubt many will read from start to finish.

That said, I have read Low Yo Yo Stuff all the way through because I think he is a master guide. Besides, he writes so beautifully, with such concision and insight, why wouldn’t you read it all?

Neither Hogg nor Marsh tend toward repetition in what they have to say about pop, or at least they are good enough writers to avoid accusations of being overly repetitive. Theirs is a remarkable skill given the short form they are working within and the thousand times they have to find a different way to tell you something is worthy of your attention. Marsh’s entries are longer, maybe 400-500 words per, while Hogg probably hits 200 words on average. That ability to introduce your subject, cut to the heart of the matter and then leave the reader, if not replete at least satisfied, is partly where the art lies.

Not only that, both are expert in sequencing so, if you are willing to work with them, they are able to tell a story of sorts.

Hogg’s reviews are like those of an older, wiser, Penny Valentine, intimate, thoughtful, often autobiographical, open to possibility, to the new, while fully aware of the past. A story is being told, nothing stands alone, everything is connected. You could collect together Valentine’s reviews and they would still be readable, entertaining and informative as they were when first published, you could not say that of any other weekly singles reviewer.

Like Greg Shaw’s singles review column in Bomp or Simon Frith’s in Let it Rock, Hogg picks his way through the dross, the vast majority of singles that were released each week, to find the unique, the challenging, the provocative, the enchanting, the mystifying, the surprising, the life affirming; a record that might say something about your life or just say ‘fuck it, let’s dance’, but it has to engage you and you with it.

Hogg doesn’t have time for snide putdowns, comic bon mots and hip self-promotion that the weeklies in the 1970s more often than not traded in, but then again he really doesn’t have much time for the third-generation rockers either, with the notable exception of Marc Bolan. There’s no Bowie, Roxy or Mott the Hoople, no stompers from the likes of Slade or the Sweet, no rock n’ roll revivalists, no pub rockers and absolutely no prog. There’s also not much disco, if any. What’s absent from his 1000 tells a story too.

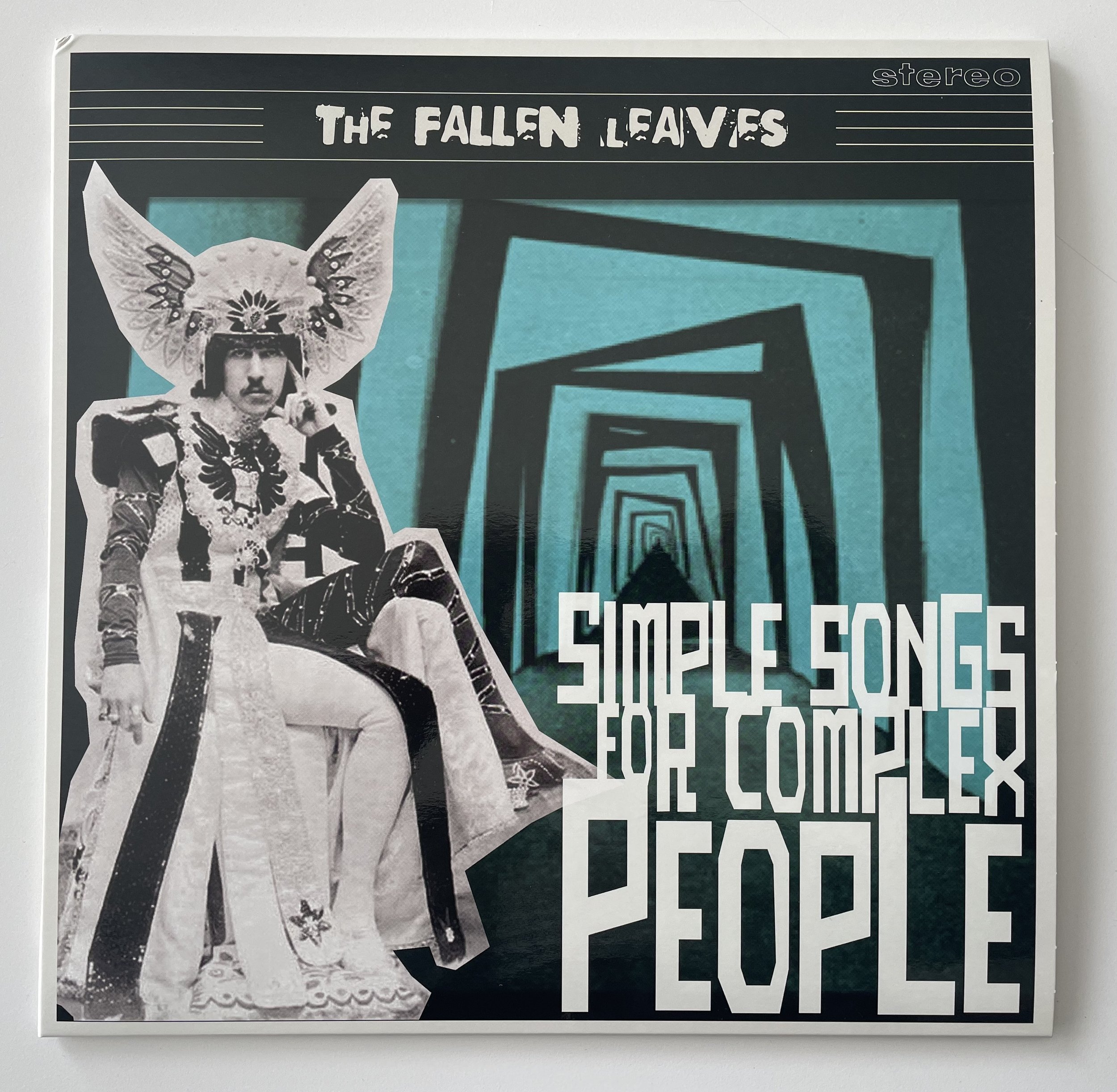

What is here are all those records he introduced me to in Bam Balam, which is like meeting an old trusted and true friend. But there is also so much more than that fanzine ever gave space to. Hogg’s list teems with Motown, Stax, James Brown, enough soul to make even Dave Godin pay attention. Ska records too and rockers by the likes Larry Williams. And so many Bo Diddley, the bedrock of it all. Girl groups, Spector and Brill Building writers are given their moment. Challenged only by the Beach Boys, the Beatles stand tall on the shoulders of all these giants. Often a review of a blues record, say by Slim Harpo, will lead into who else covered their song, such connections being the glue that holds everything together.

After his sojourn away from the glam, with punk, particularly that from New York, Hogg returns to the seventies. His enthusiasm for the new rekindled, especially by the rattle made by post-punk Scottish bands. He has much also to say about bands on 4AD, Blast First and the like, so the first half of the 80s are well covered. Rap and hip hop, however, are another absence, but then the chosen form for these acts was never the 7 inch disc.

The book sneaks into the 90s with, for me, some of the last essential seven inch singles to get pressed, those by JSBX and the Gories. I could add others from that time period, the Gibson Bros for certain, but the one’s he’s chosen make the point eloquently enough that even the good things have to end.

This is a book that will stick around as long as anybody cares about the great pop explosions of the 1960s and its reverberations. My copy is parked on the shelf next to Nik Cohn’s Pop from the Beginning and Bill Millar’s Let the Good Times Roll . . .