You’ll find few advocates for The Who’s ‘Call Me Lightning’. In fact, I’ve never read a word in its defence. Released it seems on not much more than a whim, a stop gap exercise between The Who Sell Out and Tommy or between ‘I Can See For Miles’ and ‘Magic Bus’. It touched #40 in the American charts, but was hidden beneath ‘Dogs’ on its first UK release, so doubly damned as that’s another forgotten 45. It was dismissed by Townshend at the time as ‘unrepresentative’ of the band’s current sound.

For me it is precisely its outlier status within The Who’s oeuvre that makes it a small treasure. I like their quirks, the second side of Ready Steady Who EP and things like ‘Waspman’. Their ephemera keeps the canon fresh, stops it from going stale. Anyway, Townshend was wrong. It was perfectly representative of what the band were doing in 1968, at least an aspect of what preoccupied them. It sits well alongside the Eddie Cochran covers, Johnny Kidd and the Pirates, ‘Young Man Blues’ and the like. ‘Call Me Lightning’ is part of that return they made in ’68 to teenage pop, a restatement of the ethos of rock ’n’ roll as deadly fun.

For many commentators it remains no more than a throwaway homage to Jan and Dean, but like Townshend they too are wrong. The song’s ‘dum–dum–dum–do-ays’ are more Dion and the Belmonts, New York doo-wop, than California surfing harmonies, equally loved by the band though they might be. The recording has an aggressive masculine spirit that is shared with ‘The Wanderer’ and is not there at all on ‘Little Old Lady (From Pasadena)’ or ‘Dead Man’s Curve’; it trades in a braggadocio wholly avoided by the West Coast duo.

The Who had already borrowed wholesale from Dion’s ‘Runaround Sue’ for their Talmy produced, yet at the time, unreleased novelty record ‘Instant Party Mixture’, which is a hoot; a paean to wacky cigarettes. The subject matter undoubtedly as responsible for its nixed release, coupled with ‘Circles’, as was the copyright implications of its pilfered tune.

The song had been in Townshend’s portfolio since at least 1964, the reason for its return, I like to think, was that it now had contemporary currency. In the Autumn of 1967, Nancy Sinatra released ‘Lightning’s Girl’. Lee Hazelwood’s composition would have been a perfect number for the Ronettes or the Shangri-las, which is to say it is as late to the party as the Who’s tune. ‘Lightning’s Girl’ is a warning from a girl to a boy, whose attention is unwanted, to stay away, otherwise he’ll have to answer to her boyfriend – Lightning.

Here comes Lightning down the street

While you just stand there talking

If I were you I'd start to move

And tell my story walking

About a hundred miles an hour!

If you want to know more about this cat called Lightning, well Roger can tell you:

See that girl who's smiling so brightly

Well I reckon she's cool and I reckon rightly

She's good looking and I ain't frightened

I'm gonna show you why they call me Lightning

And his ‘XKE is shining so brightly’, which if you know your Jaguars, as Pete certainly did, then he also has ‘grace . . . space . . . and pace’, which is another good reason to call him Lightning.

Maybe I’ve misheard what this is all about, but to me it sounds like a great pop conversation: ‘Call Me Lightning’ is best taken as an answer record to ‘Lightning’s Girl’. It’s the kind of exchange pop once had around Big Mama Thornton’s ‘Hound Dog’ with Rufus Thomas’ howling out ‘Bear Cat’ in return, or ‘Judy’s Turn To Cry’ as Leslie Gore’s answer to her own ‘It’s My Party’, or Neil Sedaka singing ‘Oh Carol’ and Carol King responding with ‘Oh Neil’, or, my favourite, The Satintones telling The Shirelles it’s ‘Tomorrow and Always’ in answer to ‘Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow’.

Great pop is always in conversation with itself

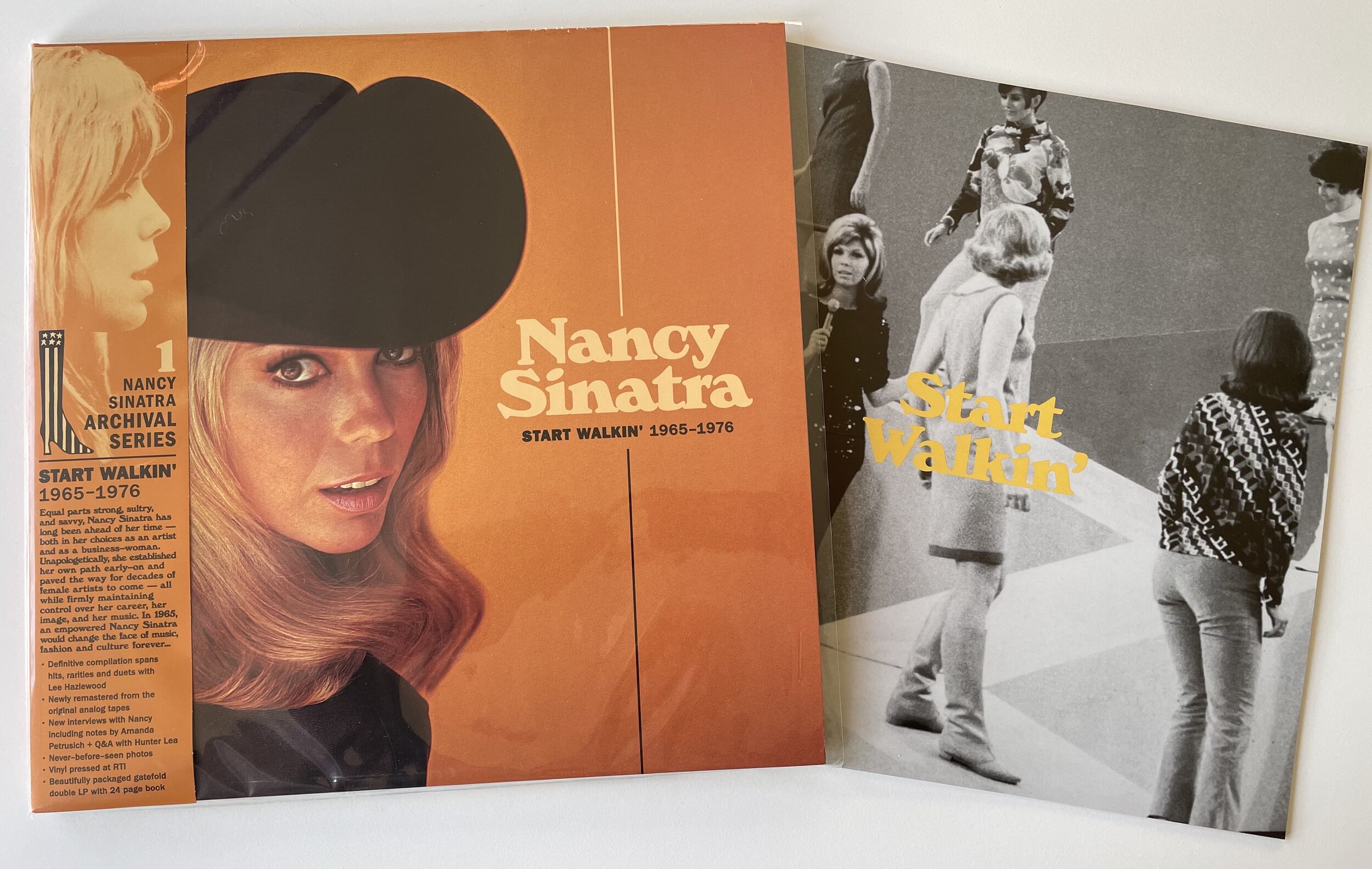

Light In The Attic have just released a double album of Nancy’s best. After having only ever heard these recordings on budget label releases, it is a sonic revelation. As always with LITA the packaging is to die for.