Paul Hogarth and Malcolm Muggeridge, London a la Mode (Studio Vista, 1966)

a Facebook post by Ugly Things’ Mike Stax tipped me off to this wonderful document of London in 1965. The book follows the illustrator’s more illustrious forebear, William Hogarth, with a series of portraits of contemporary London’s ‘vice and luxury’. ‘He shows us a city which, though transformed, has in recent years witnessed an astonishing revival of the riotous gaiety of eighteenth-century England’. Where the ancient meets the modern, so to speak

150 drawings picture the high-life and low-life of London, from morning, through noon, evening and into night where the cycle is completed.

Below are a set of images that focus on London’s youth culture. I’m particularly taken with his images of Rockers at the Ace Cafe. You also get a view of the Flamingo, Richmond’s Jazz and Blues Festival (1965), King’s Road’s long-haired youth in the Chelsea Potter, ten-pin bowling in the recently opened Excel lanes in Piccadilly, Soho’s strippers, beatniks, folkies and the area’s gay men and women.

Muggeridge’s commentary is a bit above this common rabble but Hogarth’s drawings beautifully capture the times

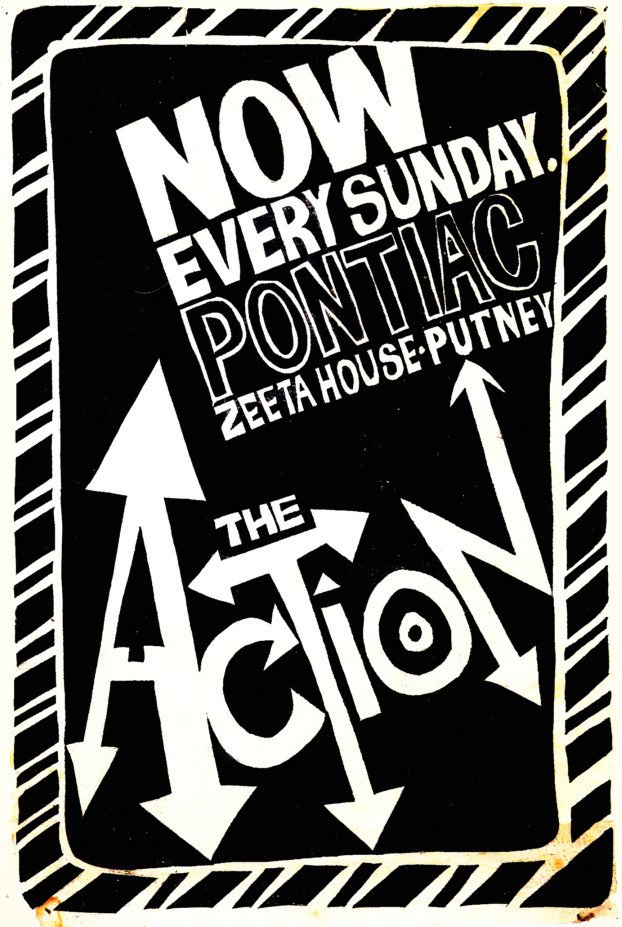

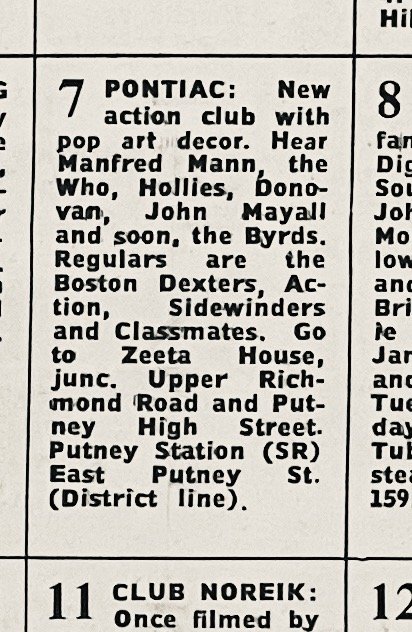

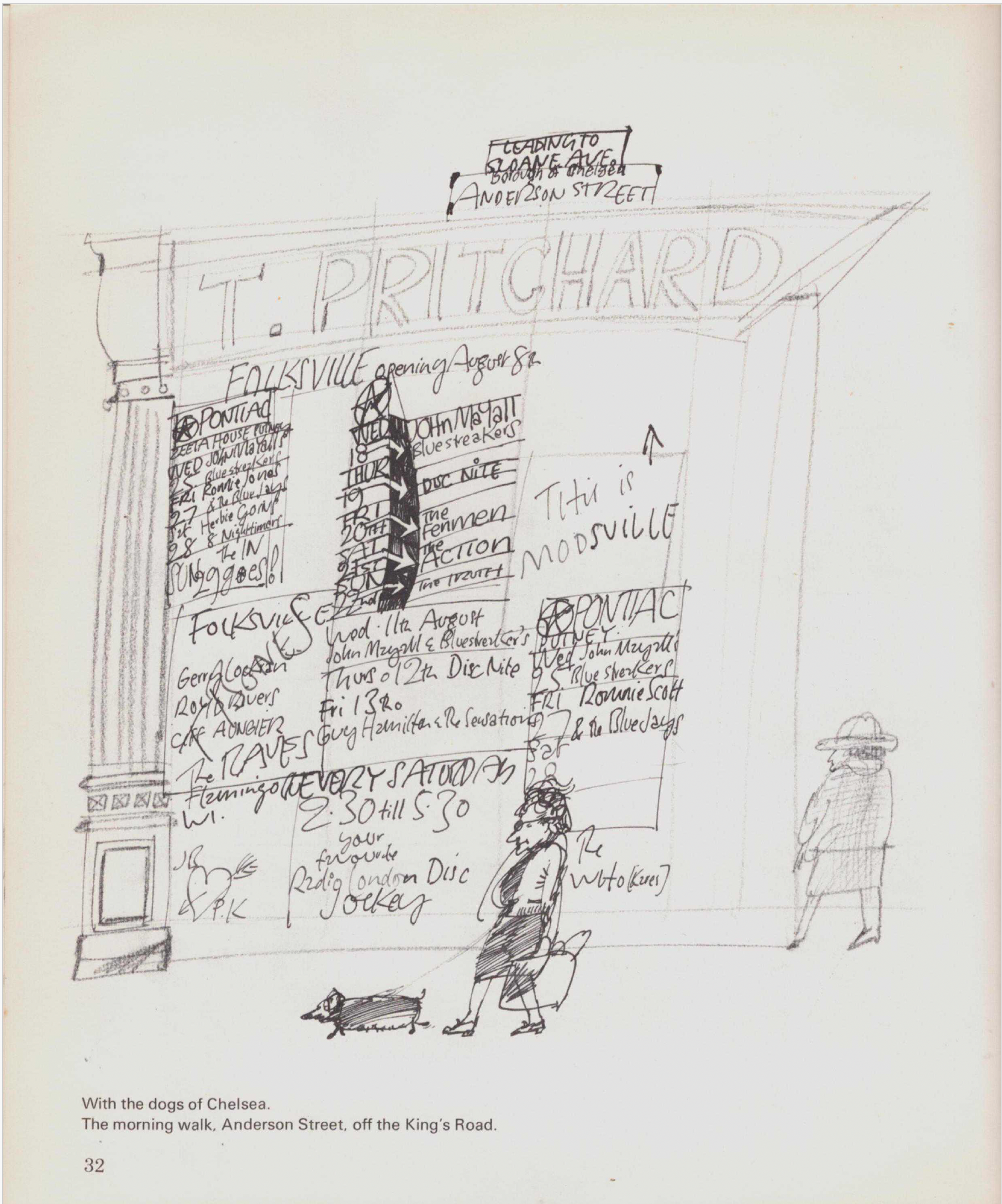

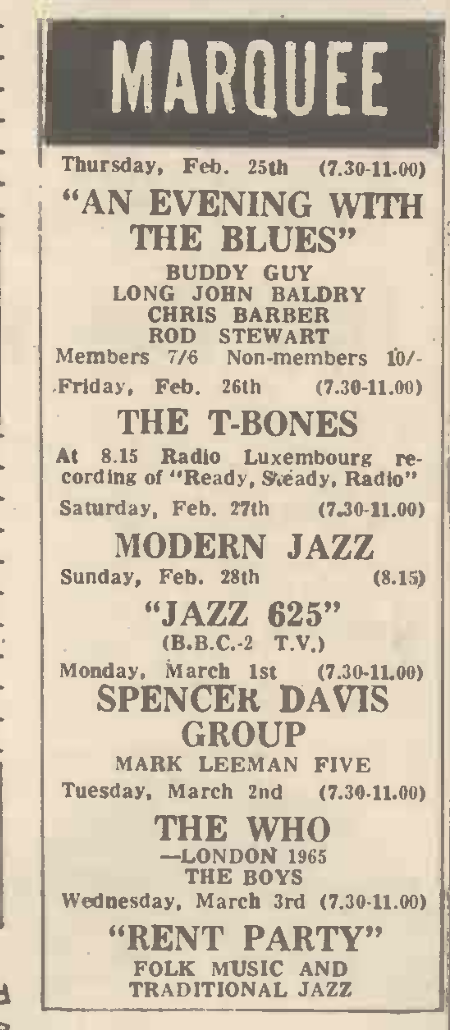

a shopfront covered in advertising for the Pontiac Club, see if your favourites are playing . . .

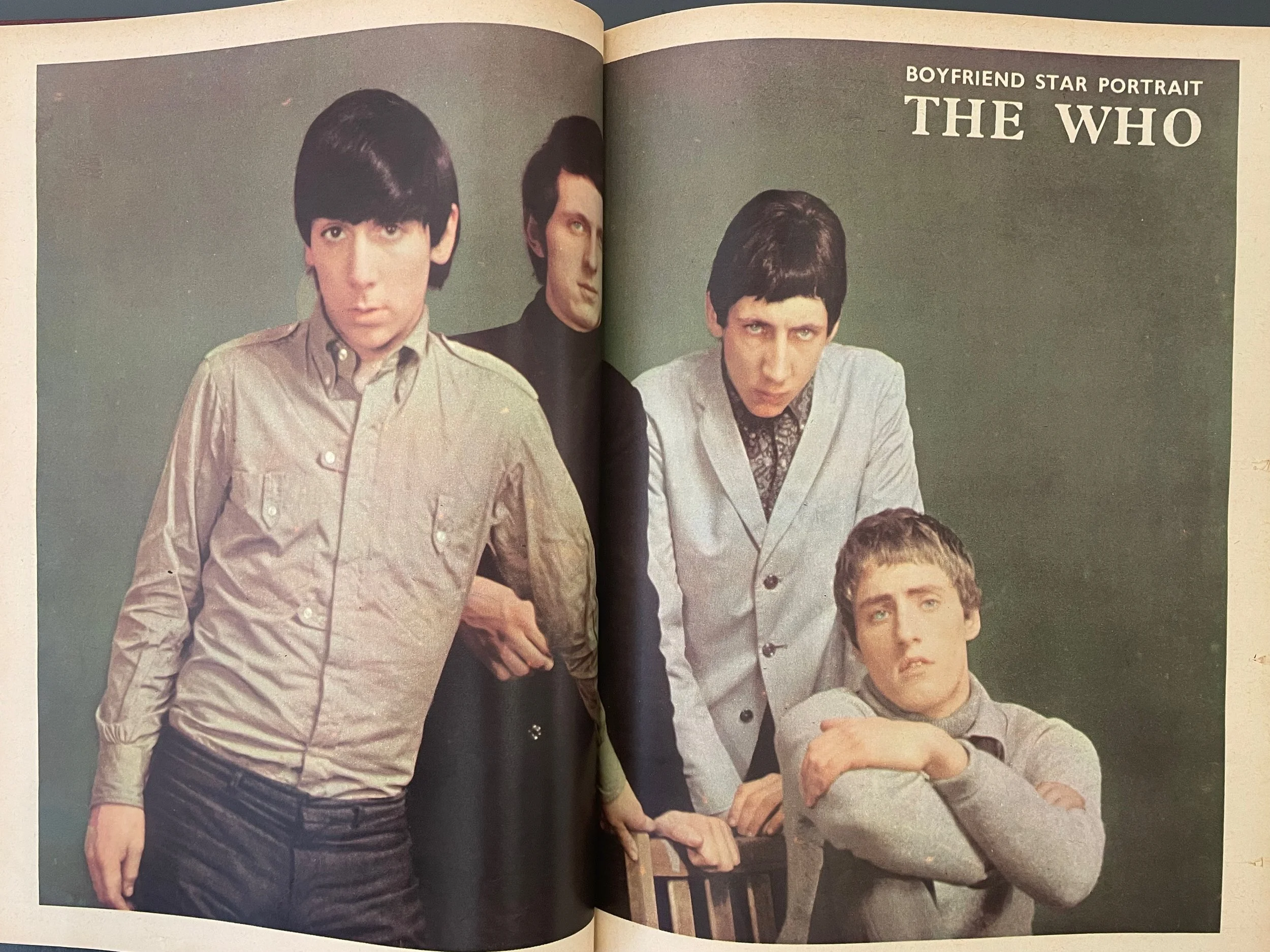

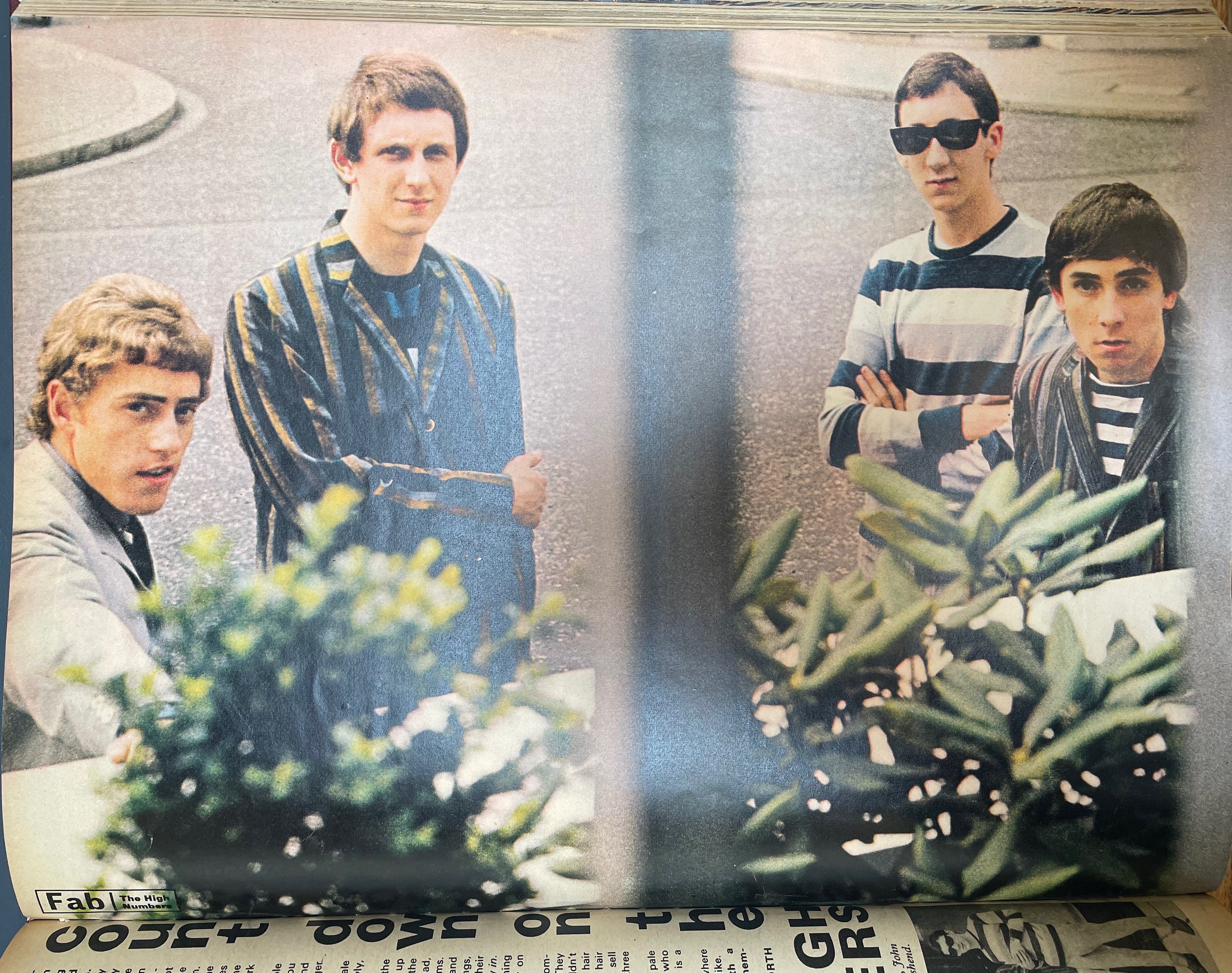

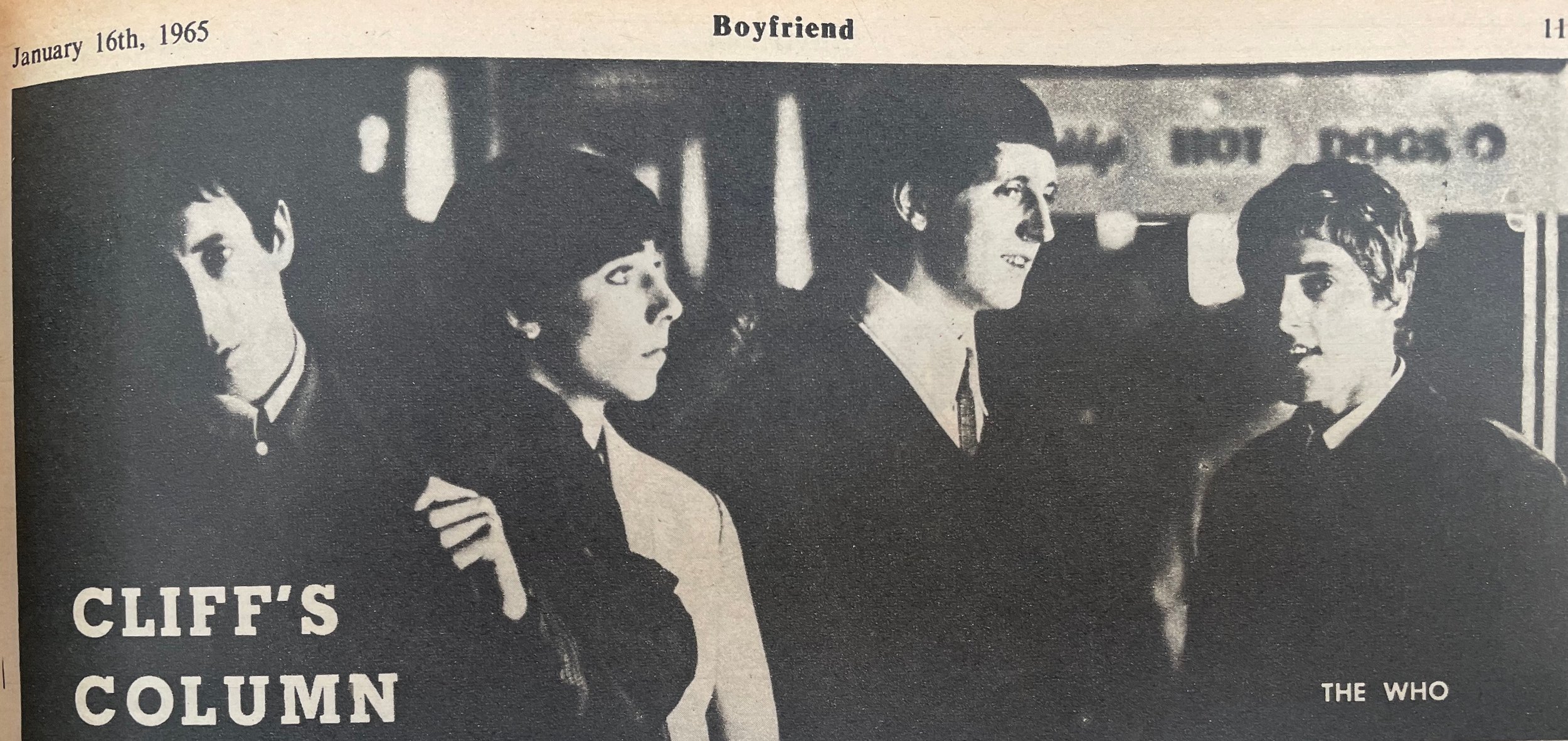

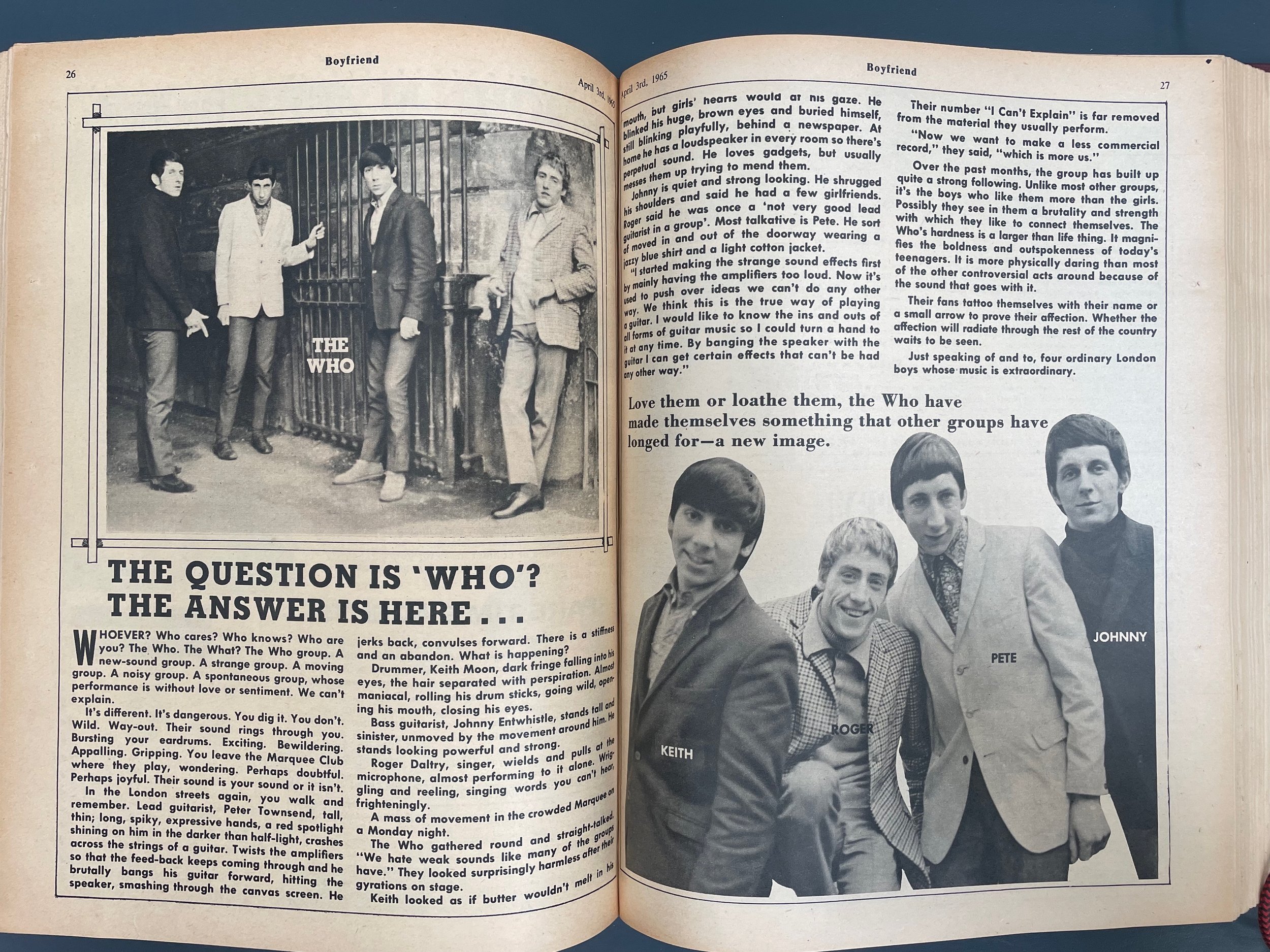

The Who bowling club!! Oh yes!!

Gary Farr and the T-Bones and Ronnie Jones captured at the 5th Annual Jazz and Blues Festival, Richmond. Saturday August 7 1965

Also on Saturday night in Richmond, Graham Bond Organisation (Dick Heckstall-Smith pictured) and Mark Leeman Five (Roger Peacock pictured)

Deerstalkers were a teenage R&B band from the Chelsea/Fulham area of London. Their singer was Barry O’Riordan who died aged 18 in January 1965 though the band carried on until at least the Summer of that year. I found no more than a couple of passing mentions of the band in the local press but Jackie magazine did publish a fan-club address for the band

Call me by my name, Tom the Pill