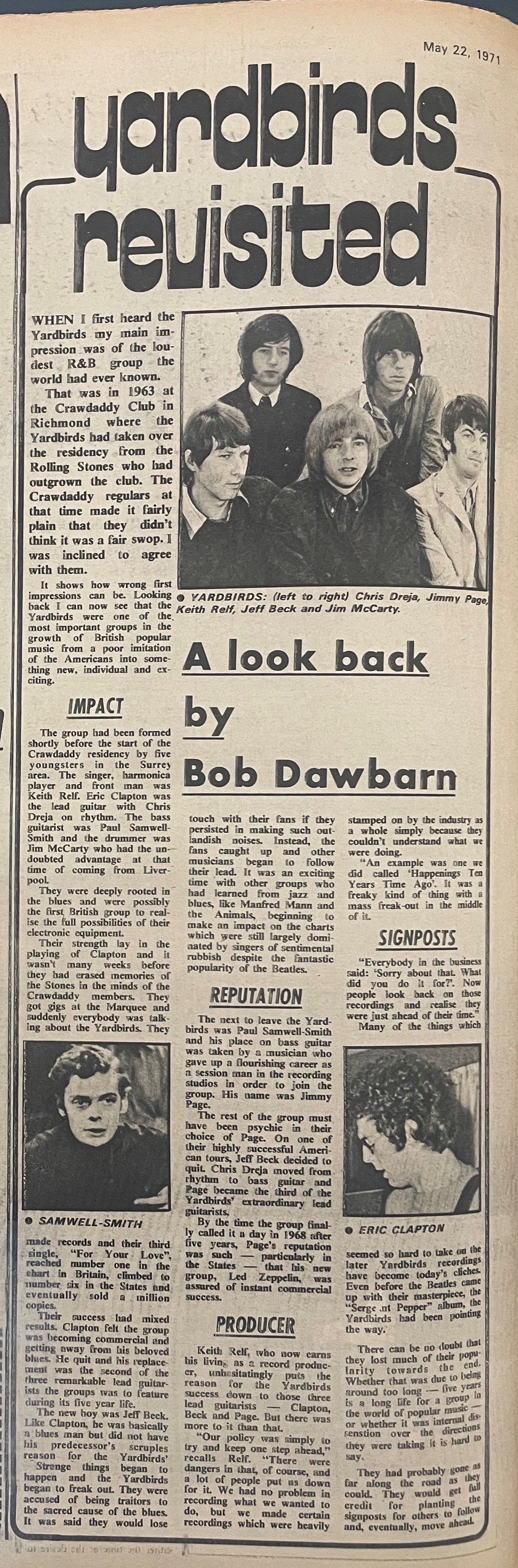

A key piece for setting the scene at the Crawdaddy Club in The Most Blueswailing Futuristic Way-Out Heavy Beat Sound was the above article from the Daily Mail in which the Yardbirds received their earliest national press coverage in March 1964.

‘Fab. Gear. Really swinging’ scene at the ‘Craw Daddy Sunday night rave’, Richmond Rugby Club where the band whipped up a frenzy and reporter Charles Greville experienced ‘the most incredible evening I have ever spent’. Some of the Mods in the audience clung upside down to the steel beams that ran along the club’s ceiling, holding on with their ‘arms and legs, and moving like a crazy caterpillar fed on pep pills’.

What a sound! With kinky fluorescent blue and scarlet light picking them out the group unleash a throbbing explosion of sound which frequently blasts the electric bulb filaments. On the floor there is a shaking mass of flesh. It reminds you of an African tribal ritual. All inhibitions are released. Frenzied youths and girls clamber on to the beams to do the Shake. They do the skipping rope – a dangerous dance in which someone is swung around while others leap over his writhing body. When space gets short they climb on to each other’s shoulders to Shake.

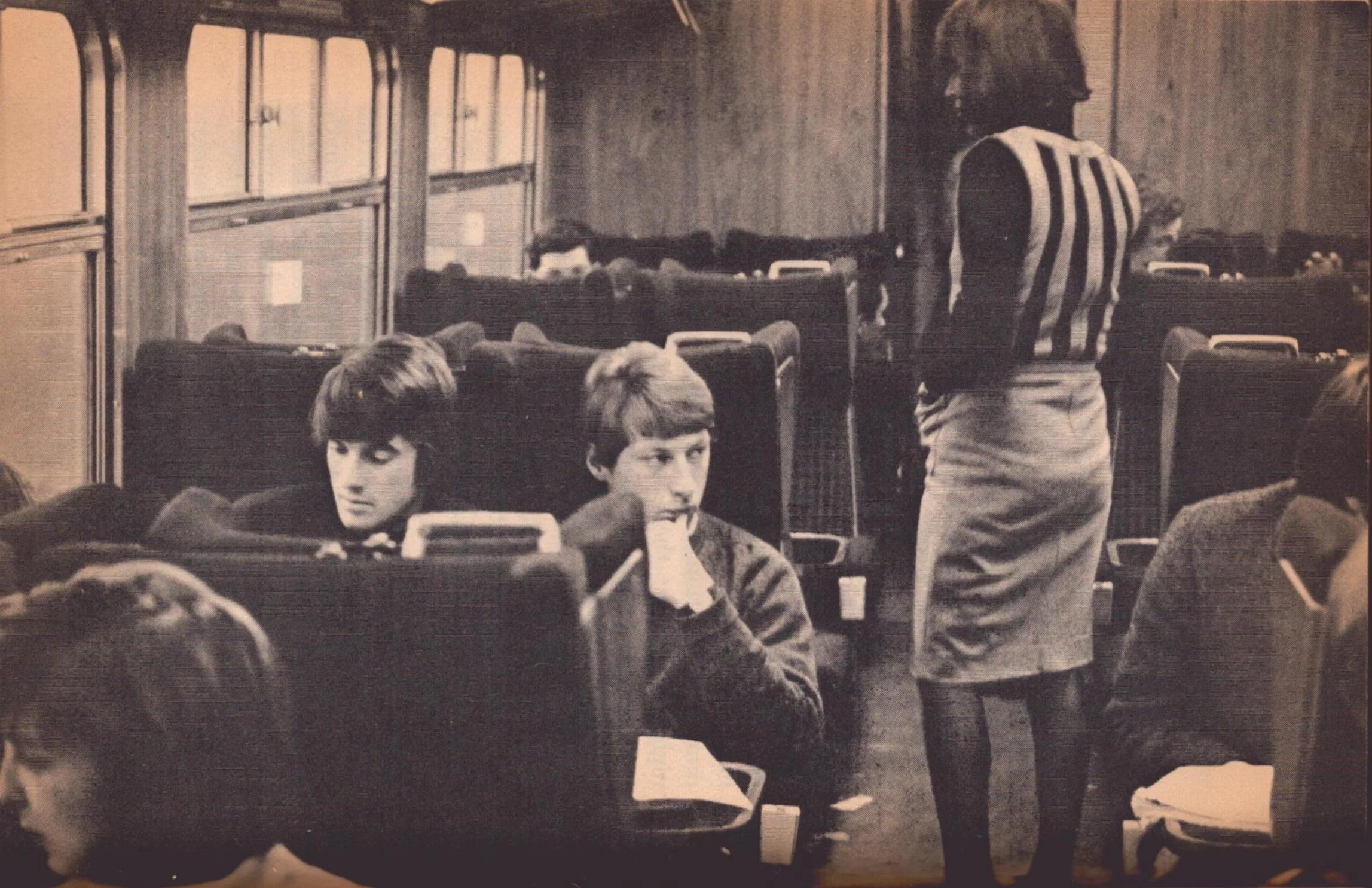

New fashions could also be seen, ‘girls in ankle-length tweed dresses; boys in jeans, bobby socks and anoraks’. In one of the accompanying photographs a boy hangs upside down above the crowd’s heads, in the other girls dance in front of the stage as Keith Relf wails into a microphone. The audience as transfixed on itself as it is on the band with witnesses to the scene, like Greville, uncertain who was the main attraction.