Melody Maker (August 28, 1965)

Not a history . . . just a scrapbook of found images and clippings I couldn’t let languish in the archives

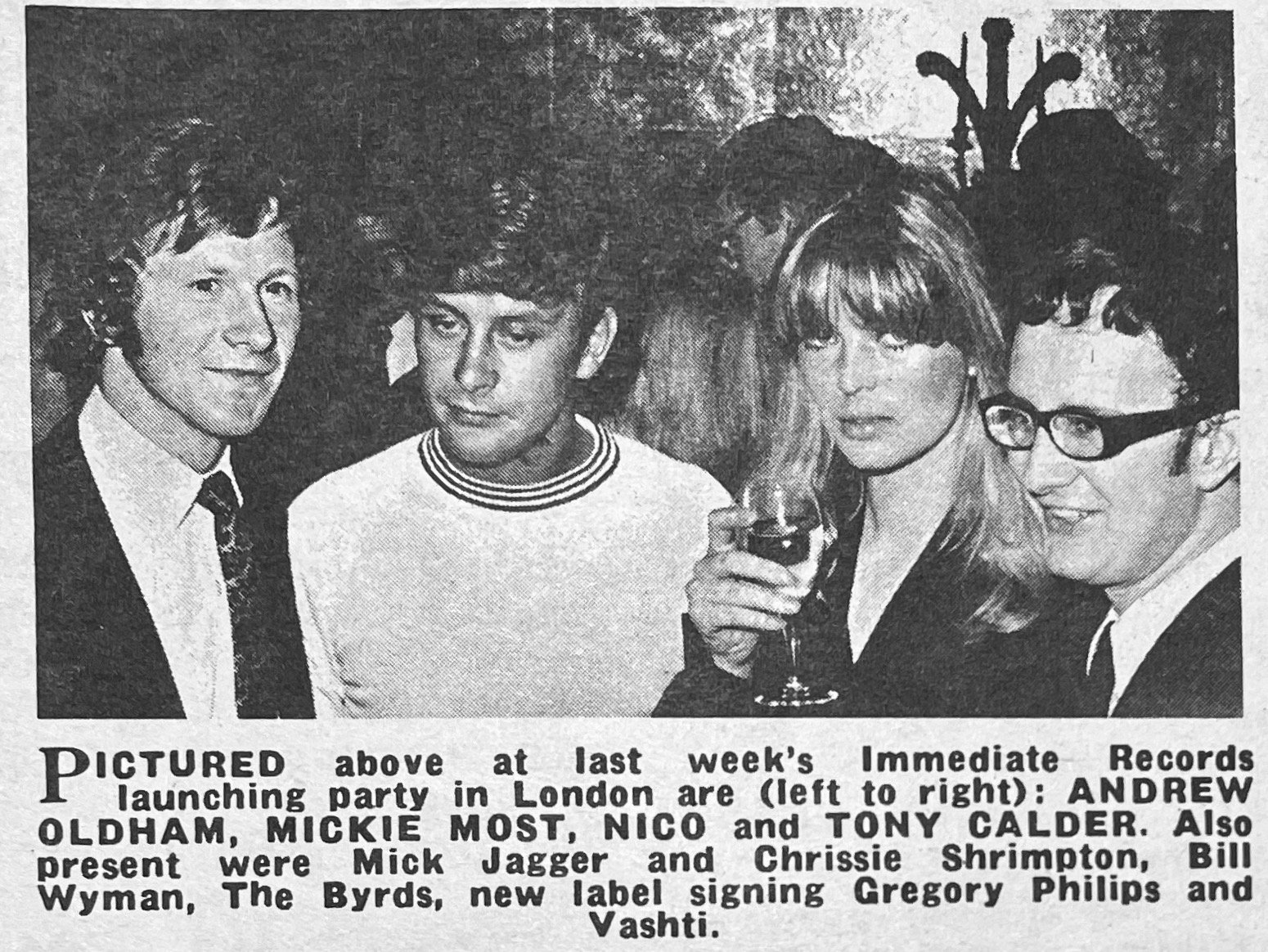

New Musical Express (August 13, 1965)

The NME used a cropped image from the press conference to illustrate an interview with Oldham from the following year (August 5, 1966)

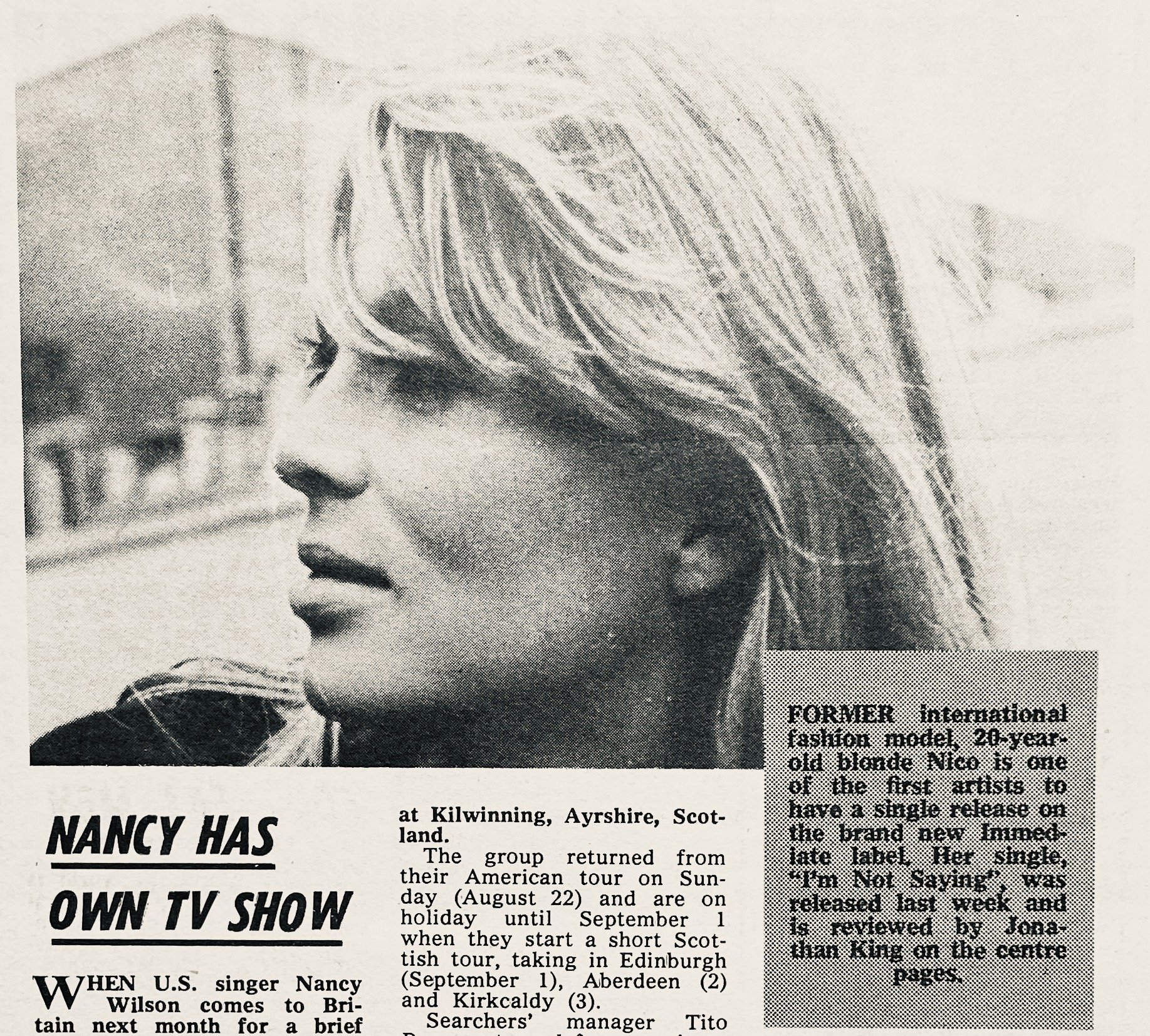

‘Niko’ . . . I’m guessing Andrew Loog Oldham phoned in his weekly column . . . Music Echo (August 14, 1965)

Music Echo (August 28, 1965)

Record Mirror (August 28, 1965)

‘I have a habit of leaving places at the wrong time . . .’ and arriving with the wrong work permit . . .

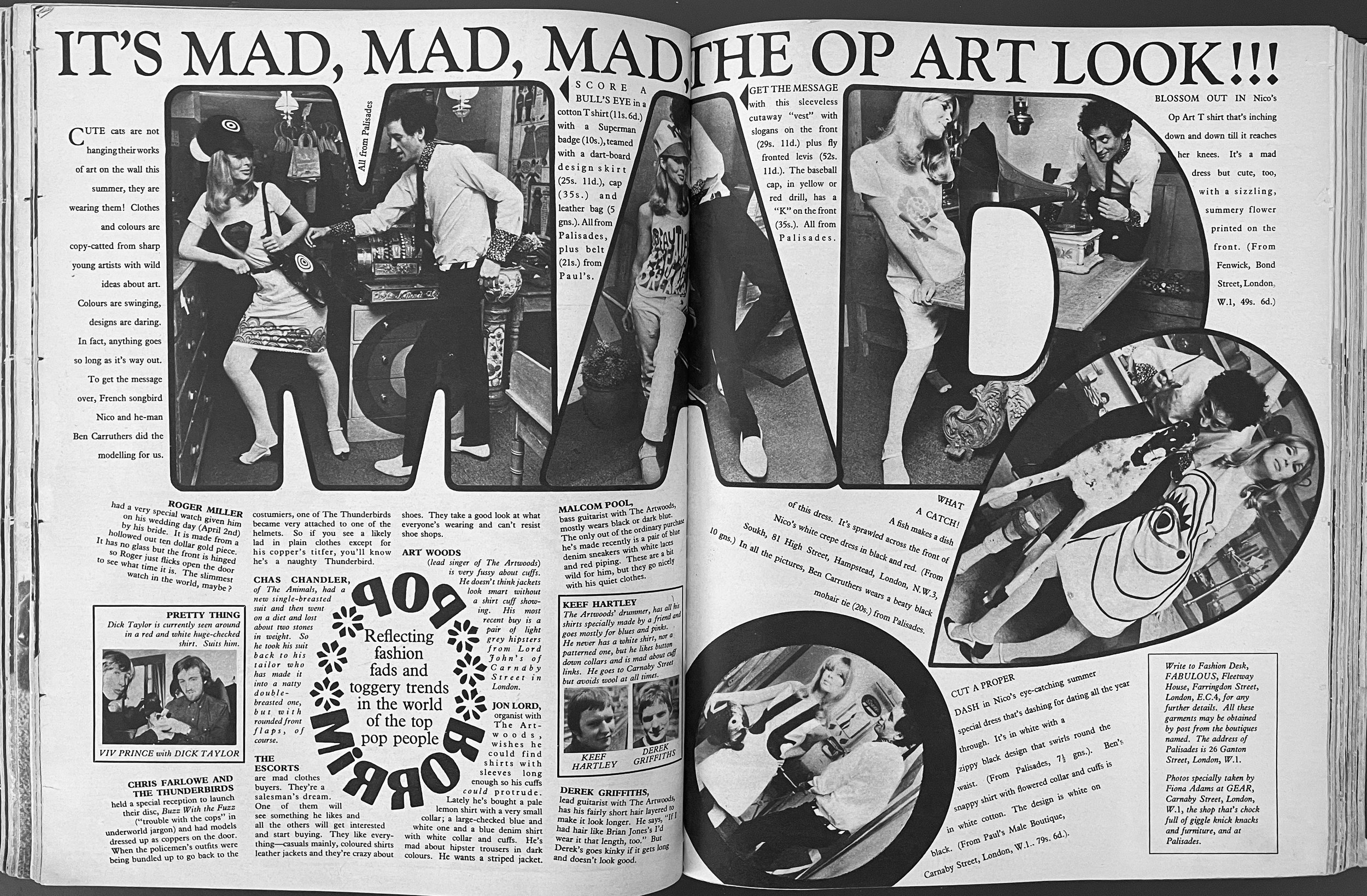

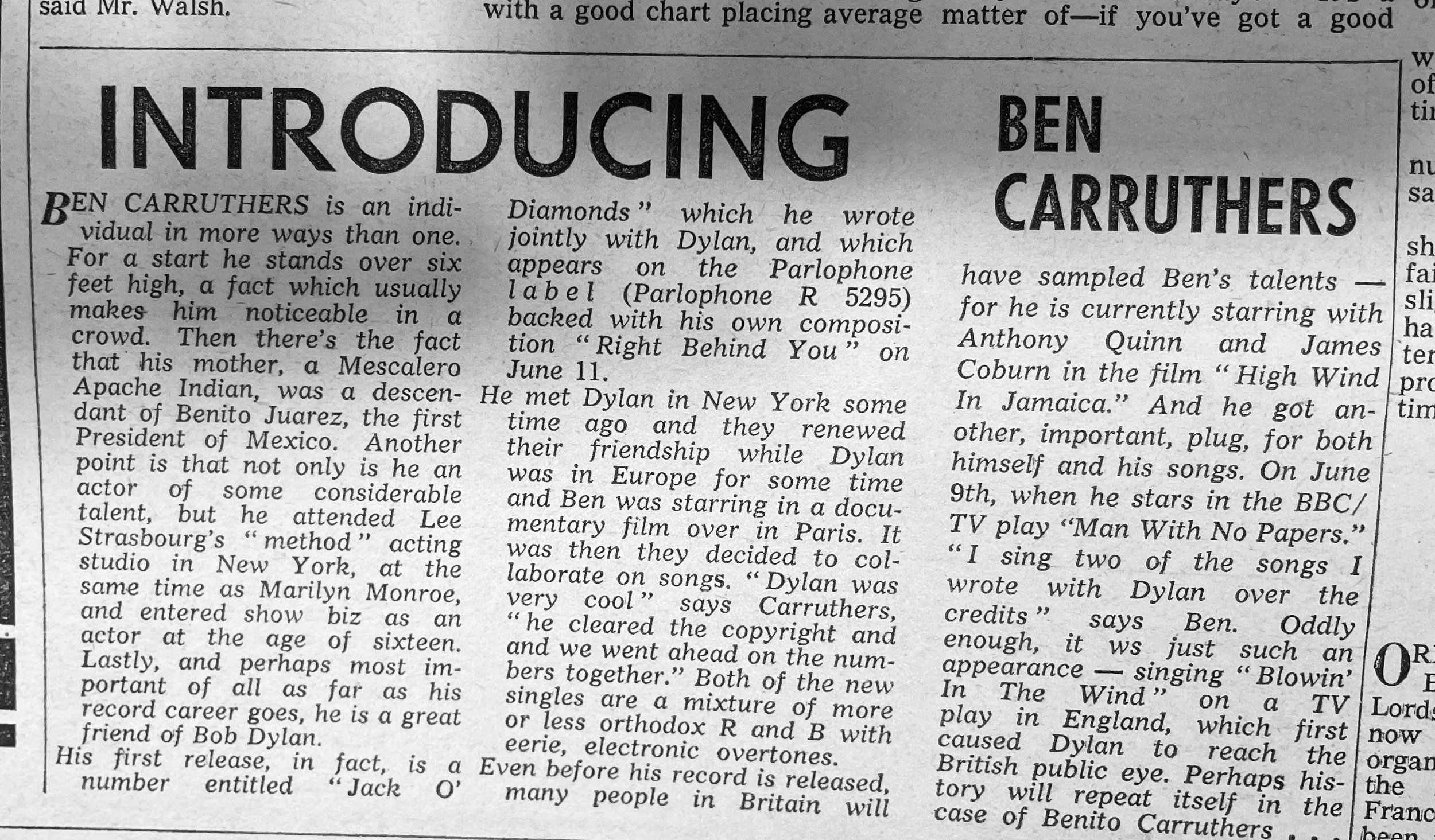

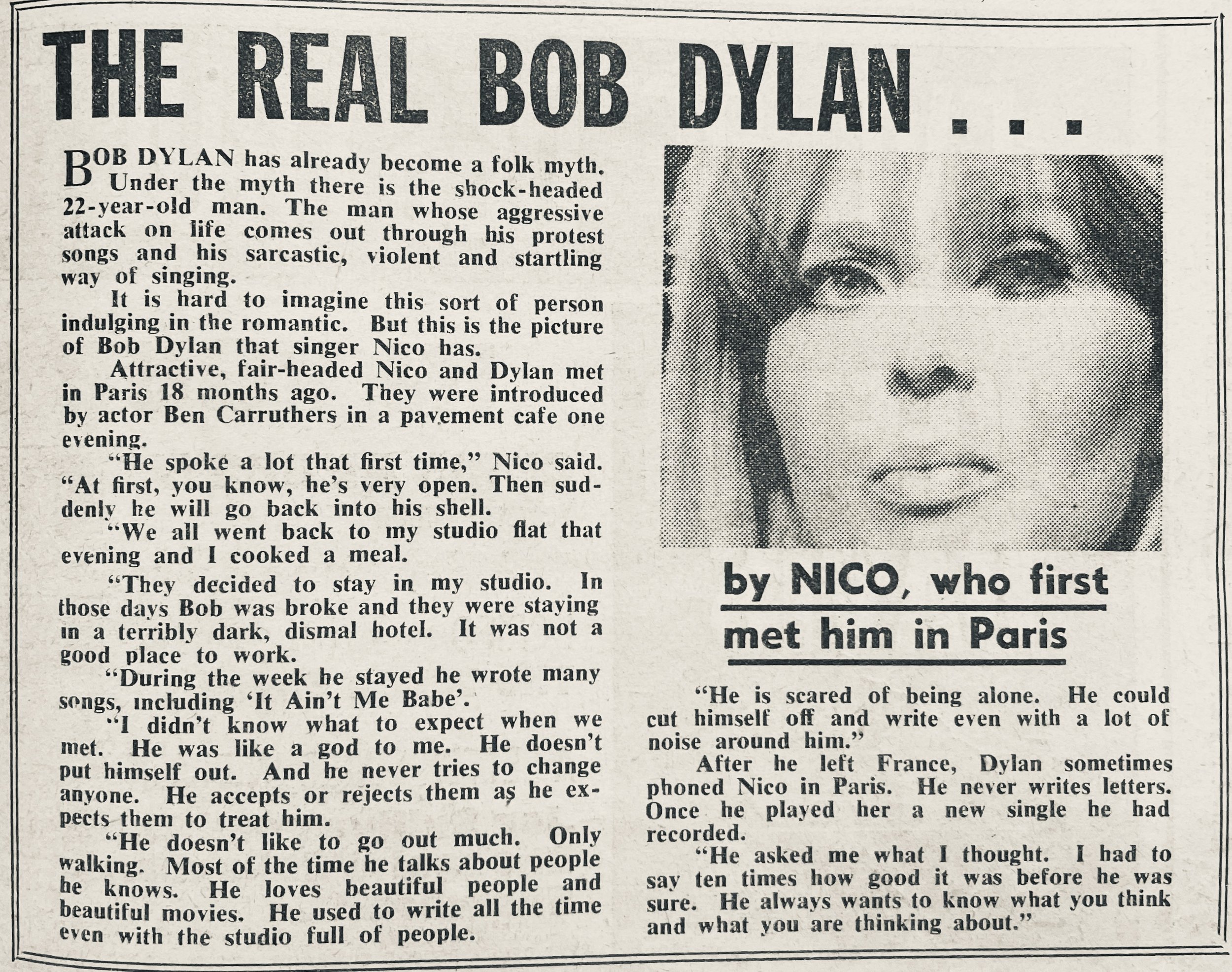

Nico in Fabulous (August 21, 1965) looking somehow out of place in a teen fashion shoot but then so does her partner in modelling . . . Ben Carruthers. He was the star of John Cassavetes’ Shadows (1959) and had just released a wonderful single, Jack O’ Diamonds produced by Shel Talmy and with Jimmy Page on guitar. Page forms one part of a triangle with Carruthers and Nico, Bob Dylna forms another (see immediately below and further down. Some great stuff on the record and Carruthers (read until the end of comments) [HERE]

Record Retailer (June 10, 1965)

Music Echo (September 4, 1965)

Daily Mirror (August 19, 1965)

Nico on Ready Steady Go! (August 13, 1965)

Evening Post (August 13, 1965)

Nico was featured three times on RSG! in 1965. Her first two appearances were June 4 and 11. For the first she gave an interview, for the second she performed Dylan’s ‘It Ain’t Me Babe’. Clinton Heylin in Double Life Of Bob Dylan (2021) suggests it was ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’ but an off-air tape of the programme lays the uncertainty to rest. Nico is accompanied by acoustic guitar and double bass in the studio and taped strings fill out the arrangement, although they sound like they are playing in another room. Her final time on the show, August 13, she sang ‘I’m Not Sayin’. None of her other appearances are thought to be extant either as audio or video. (see Andy Neill, Ready Steady Go! The Weekend Starts Here (2021)

The video of previously unedited footage is a revelation, perhaps the same could be done with Peter Whitehead’s effort

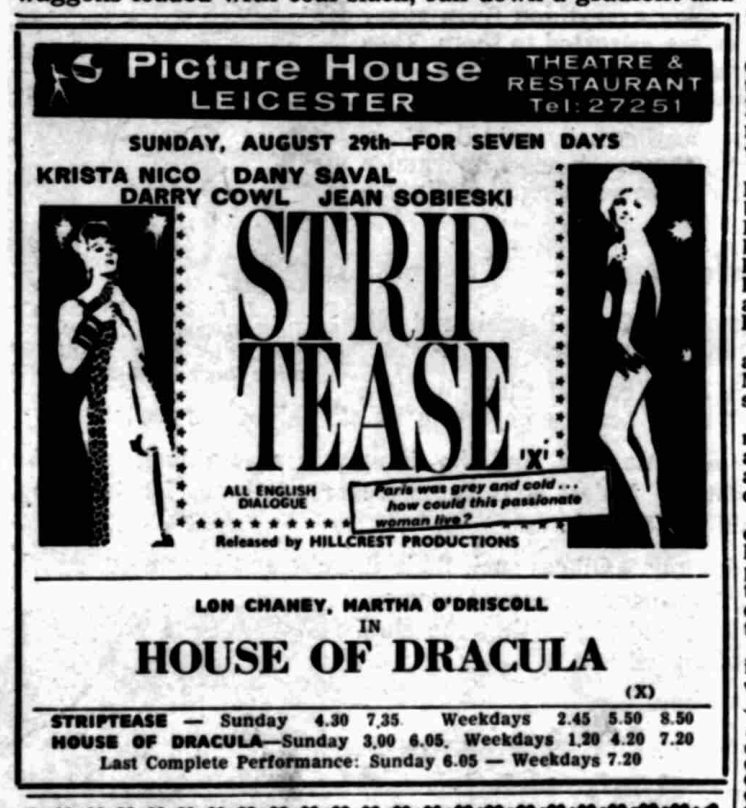

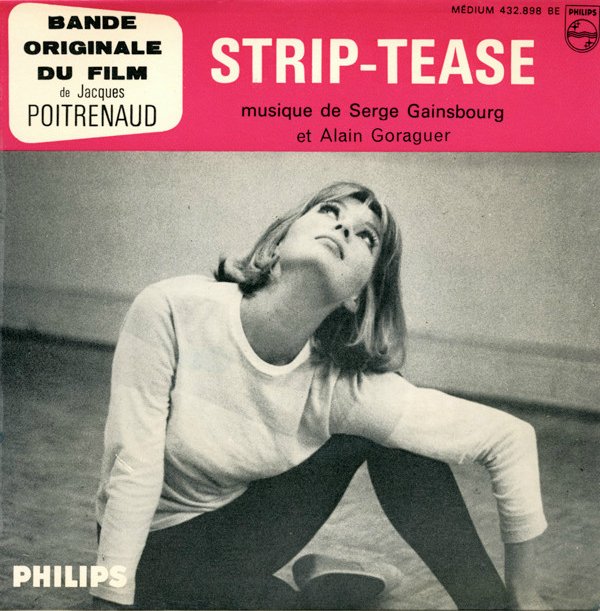

Coincidentally, while Nico was in London, her 1963 film performance, in which she was billed as Krista Nico, Striptease (X) was enjoying a London run – ‘Paris was grey and cold . . . how could this passionate woman live?’Directed by Jacques Poitrenaud, it was unimaginatively programmed with the archaic Lon Chaney Jr.’s House of Dracula (1945)

Juliette Greco sang the Gainsburg’s song on the soundtrack album but a 1962 demo with Nico has since been released [HERE]

Nico as cover star. . . from sublime to kitch

The Bill Evans Trio’s Moon Beams (1962)

Casey Anderson, Blues Is A Woman Gone (1965)

The Tattoos, Torrid Trumpets aka Trumpets Go Pops (c.1967)

The Tattoos, Swingin’ With The Million Sellers (1972)

Music Echo (August 28, 1965)

Nico caught the eye and ear of Jonathan King, pop impressario, hit maker and music press columnist. He clearly didn’t like her but she made an impact on this most square of contrarians. . . The Christmas single idea should have been realised, however . . .

Jonathan King, Disc Weekly (August 21, 1965)

Melody Maker (August 28, 1965)

Music Echo (November 20, 1965)

New Musical Express (August 27, 1965)

Andrew Loog Oldham’s advertising copy was at its most obscure in 1965, all very lysergic

Disc Weekly (September 18, 1965)

Melody Maker (August 28, 1965)

Nico appears in an outtake sequence from Don’t Look Back (1965) in conversation with Dylan’s manager Albert Grossman (Ben Carruthers also appears in the outtakes working on the lyrics with Dylan for ‘Jack O’Diamonds’)

Nico in Times Square 1966 photograph by Steve Shapiro

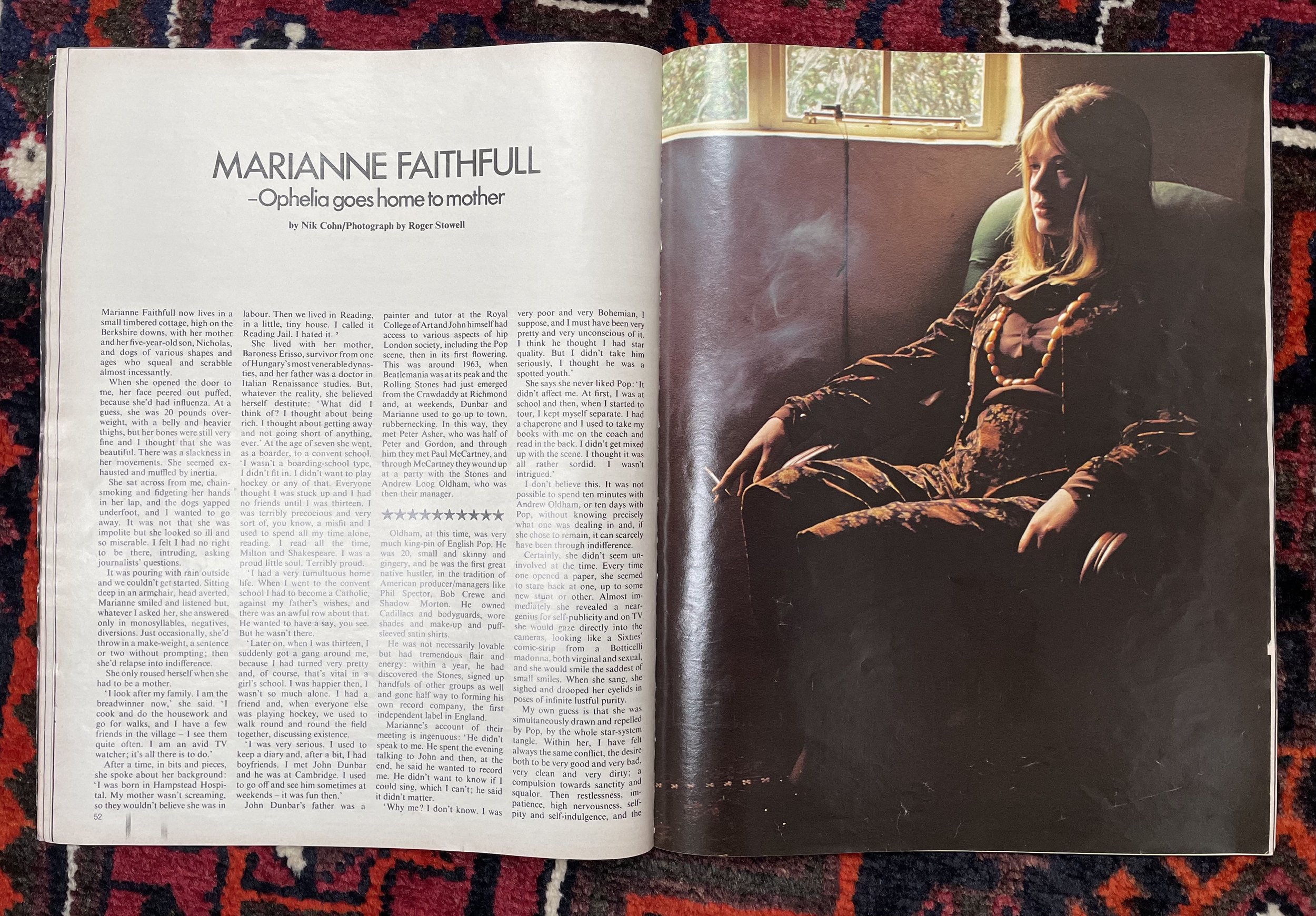

So what do you bet . . . Nico shopped at Biba’s in 1965 taking fashion tips from Marianne Faithful?

Music Echo (May 15, 1965)

During part of a wide-ranging interview with Andrew Loog Oldham, held late July/early August 1966, the NME’s Keith Altham asked him about his relationship with Marianne Faithful. He said,

‘I have decided not to take over her management because I need full control and there are too many people still with vested interest and her talents are not diversified enough anyway. I think I put that very nicely’.

Asked whatever happened to Nico? he replied:

‘Ah yes, I was glad I was right about Nico… She’s working for a group called the Underground Movement for about $11,000 for eight days in clubs like Hollywood’s The Trip’

No mention of Warhol and the Velvets misnamed, but the venue where the Exploding Plastic Inevitable played, May 3–18, The Trip – ‘the new shrine of pop culture’ — he got right, I bet he remembered her payout correctly too . . .

Disc and Music Echo (November 18, 1967): I may have missed it, but I believe this is the only contemporary review of The Velvet Underground and Nico in the British music press and it is spot on: ‘Their music is hard rock ‘n’ roll brought up to date with electricity . . .’ Read on . . . The image of Nico is from her Ready Steady Go! appearance, which I’ve not seen printed elsewhere.