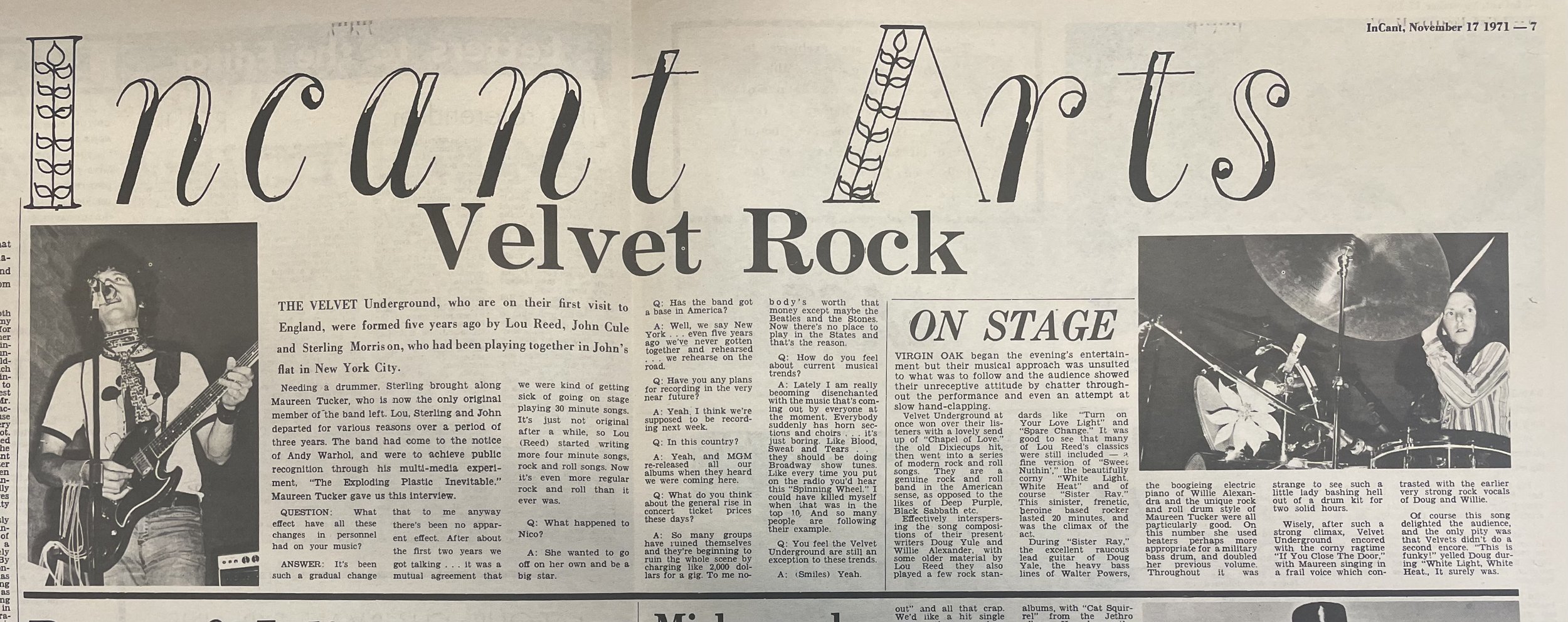

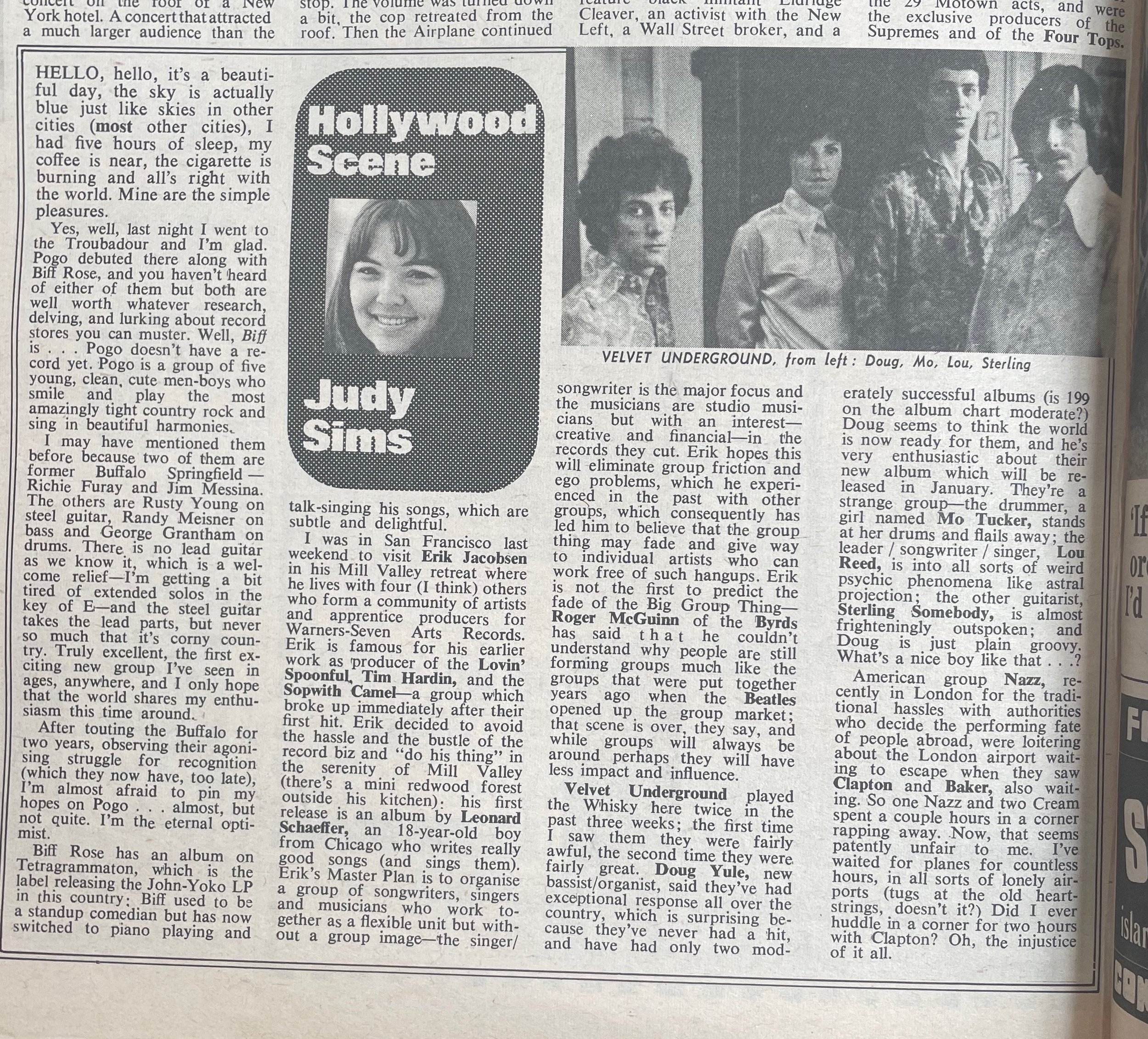

It was cheap so took a punt, flicking past the usual boring 60s into 70s acts – Joe Cocker, Jethro Tull, Grateful Dead, Blood, Sweat and Tears – I pulled up short when the VU caught my pop-eye. The unimaginative use of the 3rd album sleeve is given a bit of a boost by the editor spinning the William Faulkner quote Jean-Luc Godard had used in Breathless (À bout de souffle). He topped that with the best downer of a recommendation for the band I’ve read:

Everything in a Velvet Underground song is gray, agonized, drab and inexorable. But what they lack in hope and passion, they make up for in chilly perfection and basic rock, a good reason to accompany them down the razor-blade of life.

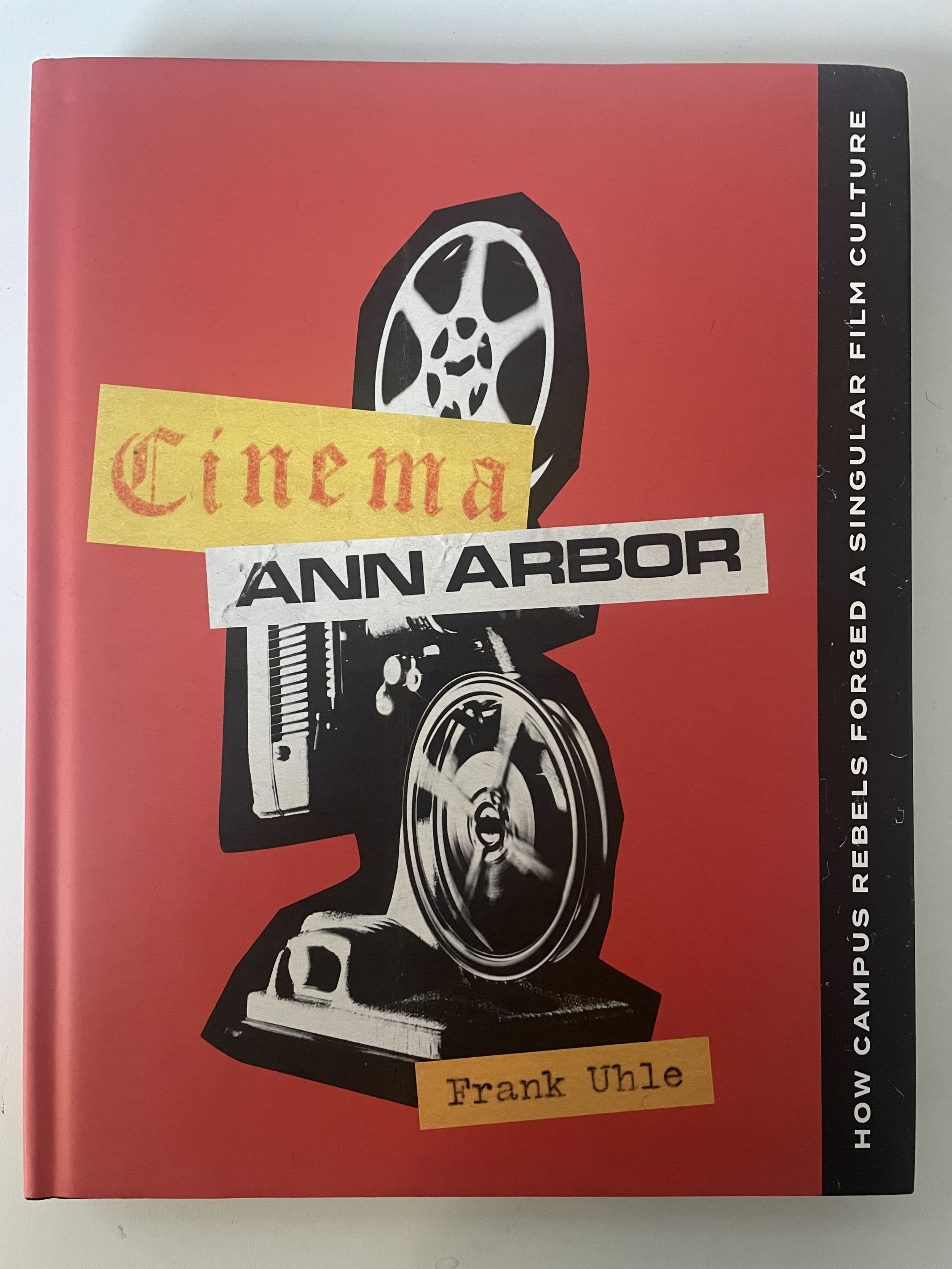

The book is organised into ten thematically arranged sections, the Velvets located in ‘Songs of Innocence and Experience’. Further on toward the end is the Marshall McLuhan influenced ‘The Medium Is The Message’ chapter which is where, good lord, the Stooges are found; all three pages of ‘em and all new to me . . . Photographed by James Roark at the Fun House sessions by the look of things – sax man Steve McKay is front and centre. The image of Dave Alexander might just be my favourite pic of him; the one of Iggy Stooge is none too shoddy either. Scott Asheton is MIA.

Rock is sex and violence. . . Rock is revolution. Rock is ceremony. It is the Stooges. . . It is Iggy Stooge, the latest high-energy uni-sex symbol, a second generation Jagger and Morrison.

The Stooges are what rock is about – stuck-up, overbearing, formless, insane, driving, intense

The Stooges: they’re wiggy.

The book ends with a dedication to John Cage and to noise and silence while Little Richard looks on – Nik Cohn would approve . . . Awopbobaloobopalopbamboom!

Unintentional, no doubt, but finding the Stooges in this context, among all the dross acts, is, I think, akin to unsuspecting record buyers discovering the band in the cut-out racks just a few years later; a chance encounter that turned the mundane into the marvellous.

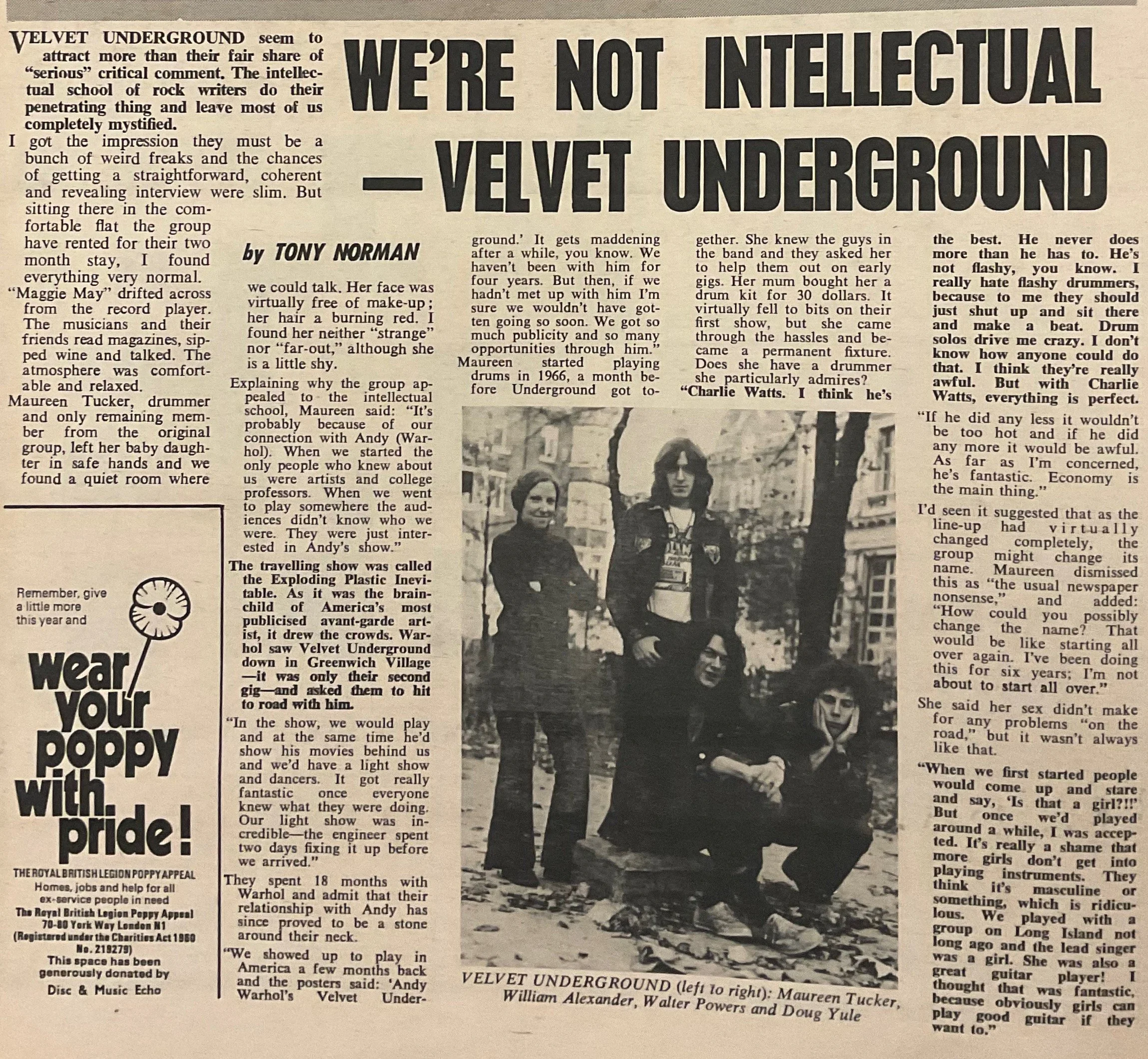

Written by Michael Ross and with original photography by James Roark – the book was published by the Los Angeles based Petersen Publishing Company in 1970, which would make the Stooges pix of the moment. If I’ve got the right man, Roark was best known for his sports photography. Ross I know nothing about.