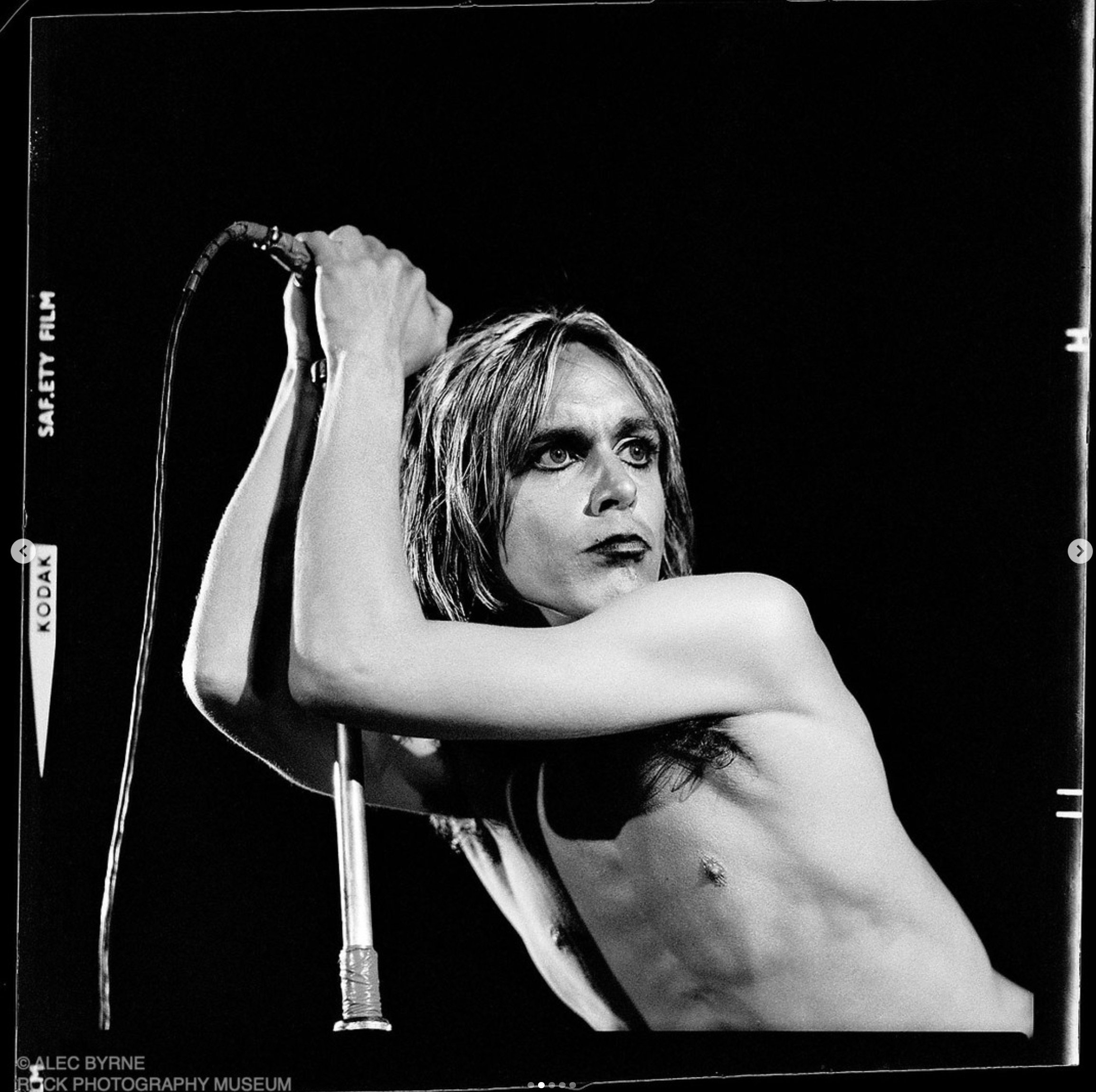

In May 2020 a test pressing of Raw Power went up for auction on eBay, the price eventually going beyond the few shillings I had saved, but I kept the images that were posted

Dated December 8, 1972, three months before its US release in March, 1973. it should be in a museum or even better in my collection, it’s a one-off (or one of a very few). It would be the jewel in any collector’s crown. – a fetish item for the ages. But, you know, it is just a white label pressing of a stock copy, I’ve got a couple of those and, having not won the auction, I’ve still got the coin in my pocket.

But take a closer look. The timings suggest side one and two were flipped, which adds to the uniqueness. Then look again, side 1 has five tracks, not the four on the release version, and side 2 has only three.

So what was the running order? Dave Marsh’s hyper-enthusiastic review in Creem’s March 1973 edition gives a couple of clues.

He lists the title track as the second band on the top side, so my guess is it still kicks off with ‘Search & Destroy’, but which mix I wonder? Iggy’s? Or Bowie’s as found uniquely on the original UK release? Whatever, ‘Gimme Danger’ is the third track. After that no more clues from DM.

Working with the timings given on the white labels, and some some addition and subtraction on my part, Side 2 must be:

Your Pretty Face Is Going to Hell

I Need Somebody

Death Trip

Side 1 then would look something like this:

Search and Destroy

Raw Power

Gimme Danger

Shake Appeal

Penetration

How’s that play in your head? While you’re pondering over this sequence and whether it rolls better this way than it does following Tony Defries’ edict that the songs needed to go fast one, slow one, fast one , as was eventually released, Dave Marsh wrote that their are ‘nine songs’ on the album, not the eight we have and love, perhaps he was shit at counting or adding up . . . or he had a different review copy. Think on that dear collector.

For those Raw Power devotees out there, here’s Mick Rock’s little known review of the album in the UK skin mag Club International (July 1973). More of this kinda thing is buried deep in Pin-Ups 1972: Third Generation Rock ‘n’ Roll. Available to preorder or in the shops early next month . . . Get Some!