The Staffordshire Evening Sentinel has the scoop of the day . . . Media manipulator, pop-svengali, orchestrator of outrage, Simon Napier-Bell made his biggest splash as manager of John’s Children in a pop column syndicated in the local press. He was no doubt aiming for Atticus and the Sunday Times but ended up with Alan Jones – pop correspondent for the Potteries and all points east . . .

Staffordshire Evening Sentinel (April 8 1967)

On the verge of joining the Who on a tour of Germany, John’s Children were interviewed by Jones for Staffordshire and Lincolnshire’s regional newspapers. Napier-Bell set out the band’s manifesto:

John’s Children are outrageously arrogant because they find other people ugly, devious and boring. They are grippingly honest because they are not sophisticated enough to be devious. They look naïve because they are young, clean and sweet.

Things got easily out of hand; at one gig, the band explained, ‘“We were yelling Sieg Heil, the German marching cry, and the audience were shouting it back” . . . “They liked the sound of the cry . . . Nothing political. They just liked the sound” . . . Whatever they played they liked it loud,’ wrote Jones.

Would they revive the war cry ‘Sieg Heil’ on the German tour? ‘Definitely,’ replied John. Offensive to the German audience? He gasped: ‘Surely not. People cannot be that thick. It is a fascinating beat, that is all there is to it.’ To show his innocence, John claimed he did not know what Sieg Heil meant. But then, that is part of the pop mystic. With a knowing smile, he tried to explain a new single the group were making. ‘It’s about a man who plays funerals in his backyard.’

A slightly longer version appeared earlier in the Lincolnshire Echo

Lincolnshire Echo (April 4 1967)

Because it was a good pop story, Jones willingly played along with Napier-Bell’s game of manufactured outrage; it was good enough anyway for him to construct at least a superficial display of suspended disbelief; certainly seductive enough to have him regularly review the band’s records and to do so positively

Lincolnshire Echo (January 30 1967)

Lincolnshire Echo (May 16 1967)

Lincolnshire Echo (August 4 1967)

Lincolnshire Echo (November 6 1967)

Lincolnshire Echo (June 10 1968)

Surrey Advertiser (March 11 1967)

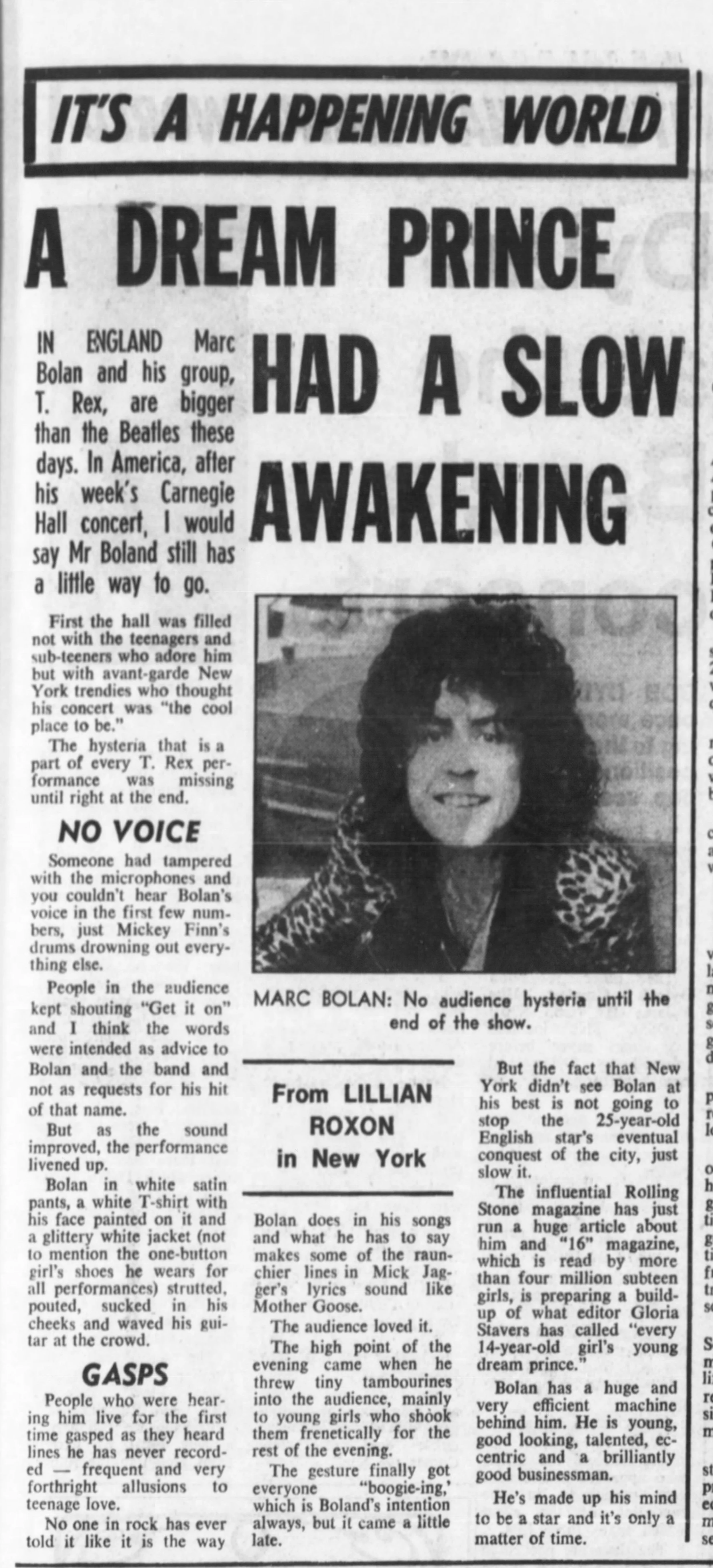

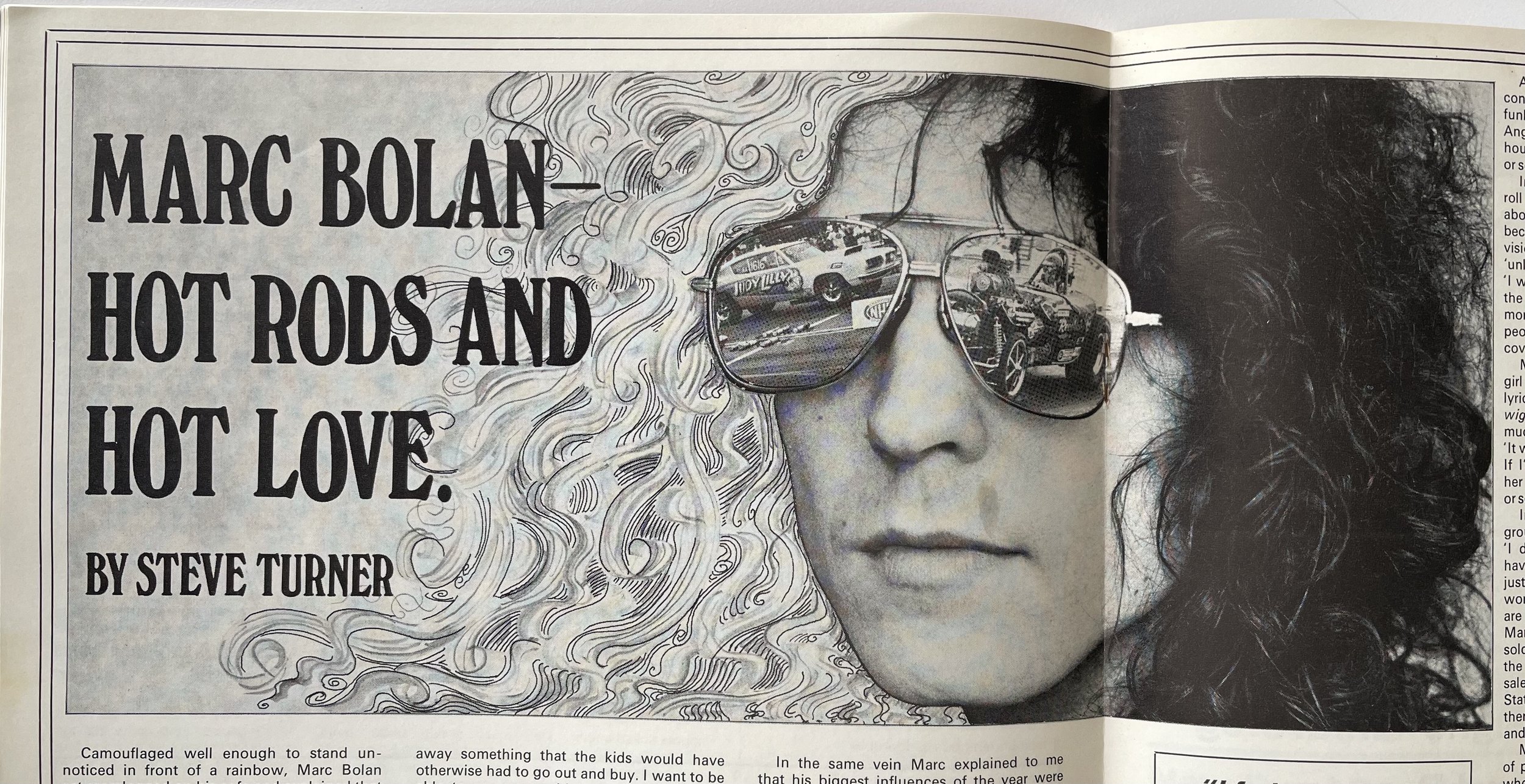

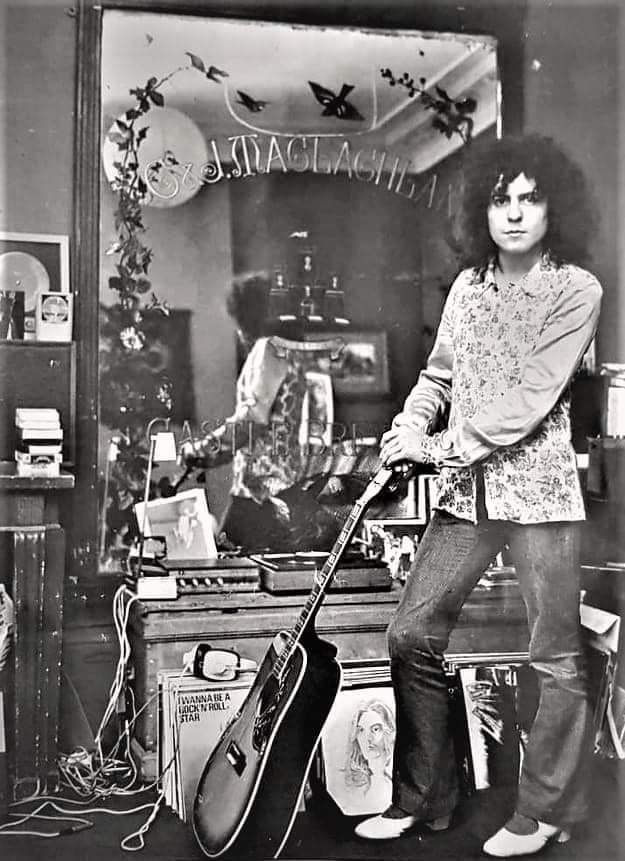

Jones would continue to review the new pop releases into the next decade and was always happy to boost Marc Bolan from the early days Tyrannosaurus Rex and into the era of Trextasy:

The glamour is what other people see in it. But there’s not much glamour sitting in a studio being photographed. What is exciting is having the vision to see the end product.

Staffordshire Evening Sentinel (October 2 1971)

Leicester Mercury (March 29 1967)

‘Owing to illness Wayne Fontana . . . will be unable to appear

Somerset Guardian (June 23 1967)

‘The first genuine flower power group to visit Nottingham . . ‘

Nottingham Evening Post (July 26 1967)

County Post (September 8 1967)