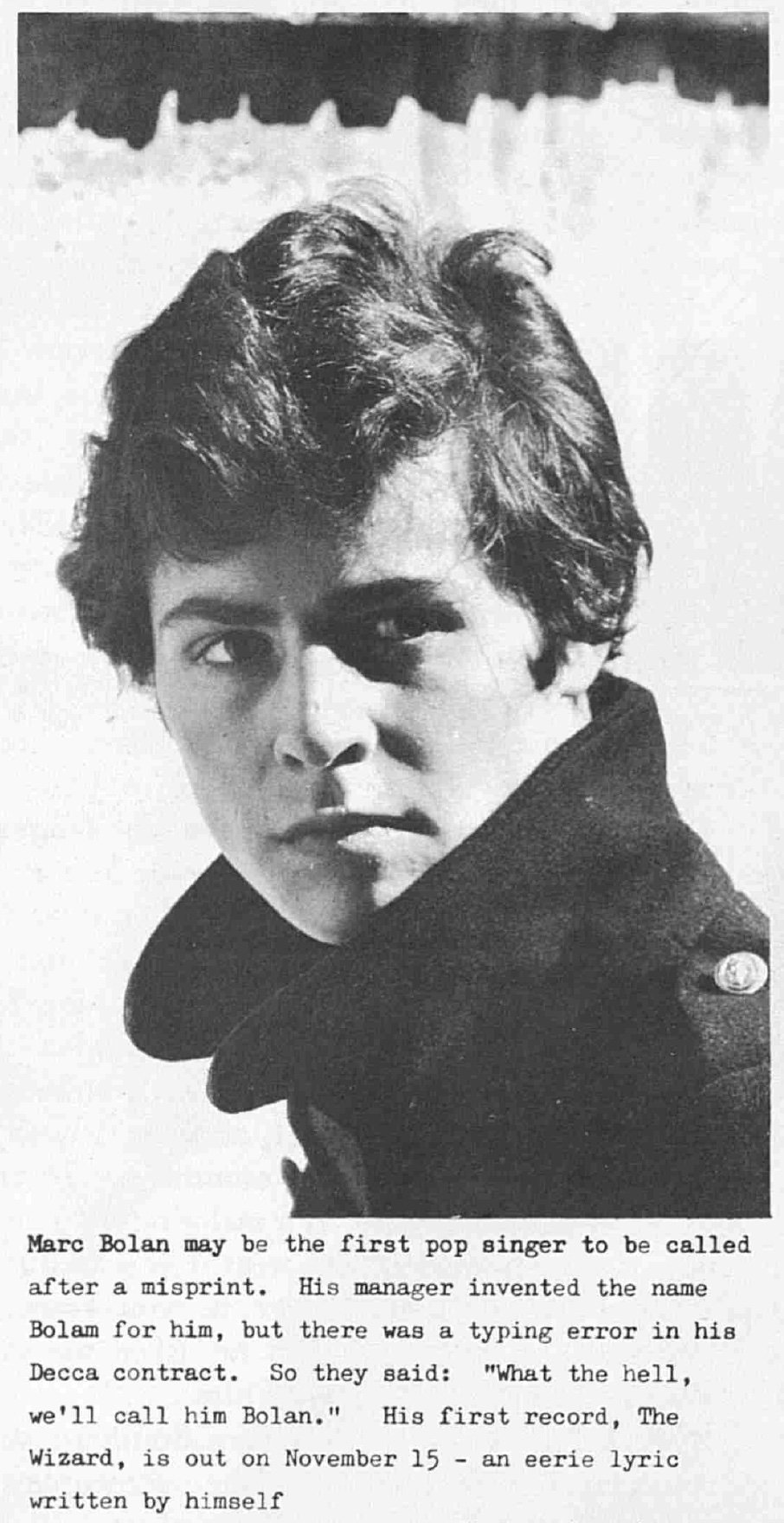

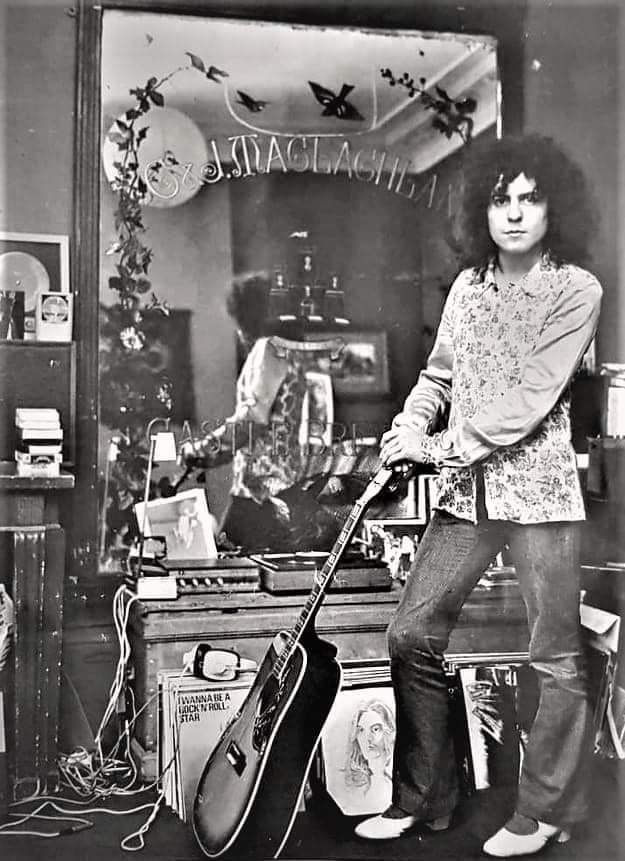

‘The gods have been very kind. Everything has fallen into place beautifully’

– Marc Bolan

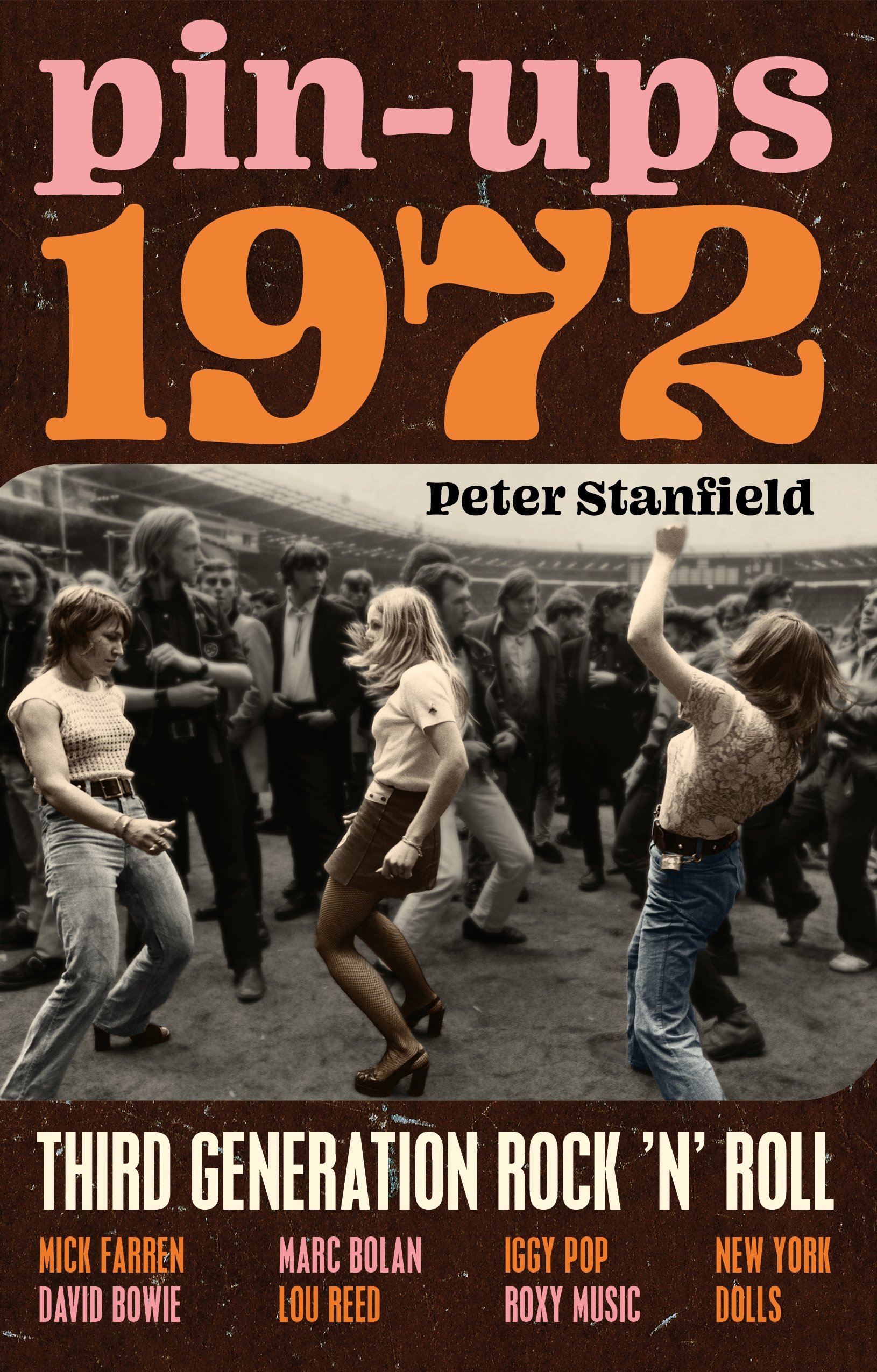

Music Now was a weekly paper that ran for 50 issues between March 21 1970 and February 21 1971. It was edited by Jim Watson, formerly of Record Mirror and used a small staff of correspondents – Derek Boltwood, Tony Norman, Karen de Groot and Dai Davies formed the core of operations. Columnists included Simon Stable, their man about town in Manchester and Ladbroke Grove, Max ‘Waxie Maxie’ Needham’s fusillades on rock n’ roll, Sapphire’s superior Reggae Page and Pete Senoff’s America Now.

With its emphasis on progressive rock, Music Now’s most obvious competitor was the recently launched Sounds (October 1970), which it differentiated itself from with its use of colour photographs on the cover and in some of its editorial content.

Rarely referenced, Music Now is something of a small, untouched, treasure trove. Here are the key pieces that covered T. Rex’s move from the underground into the light in those heady, mercurial days.

T. Rex made their first appearance in the September 26 issue with a front page announcement that the maximum ticket price for dates on their upcoming tour would be 10/-. Marc said:

Tour prices in general are inflated. We can afford to do it for less. We don’t have truck-loads of equipment. It’s more help to the kids that we do it as cheaply as possible.

The ploy of making themselves affordable and therefore accessible to a younger audience, something that was carried over with their record releases, was both admirable and a canny bit of marketing that would pay out unbelievable dividends in the new year.

There’s also a fascinating bit of ephemera too with the postscript on Marc’s relationship with Mark Volman and Howard Kaylan and the apocryphal news, I presume, that they had produced a cover of his ‘Mustang Ford’ with Freddie ‘Talahassie Lassie’ Cannon . . . Now, that I would have loved to have heard . . .

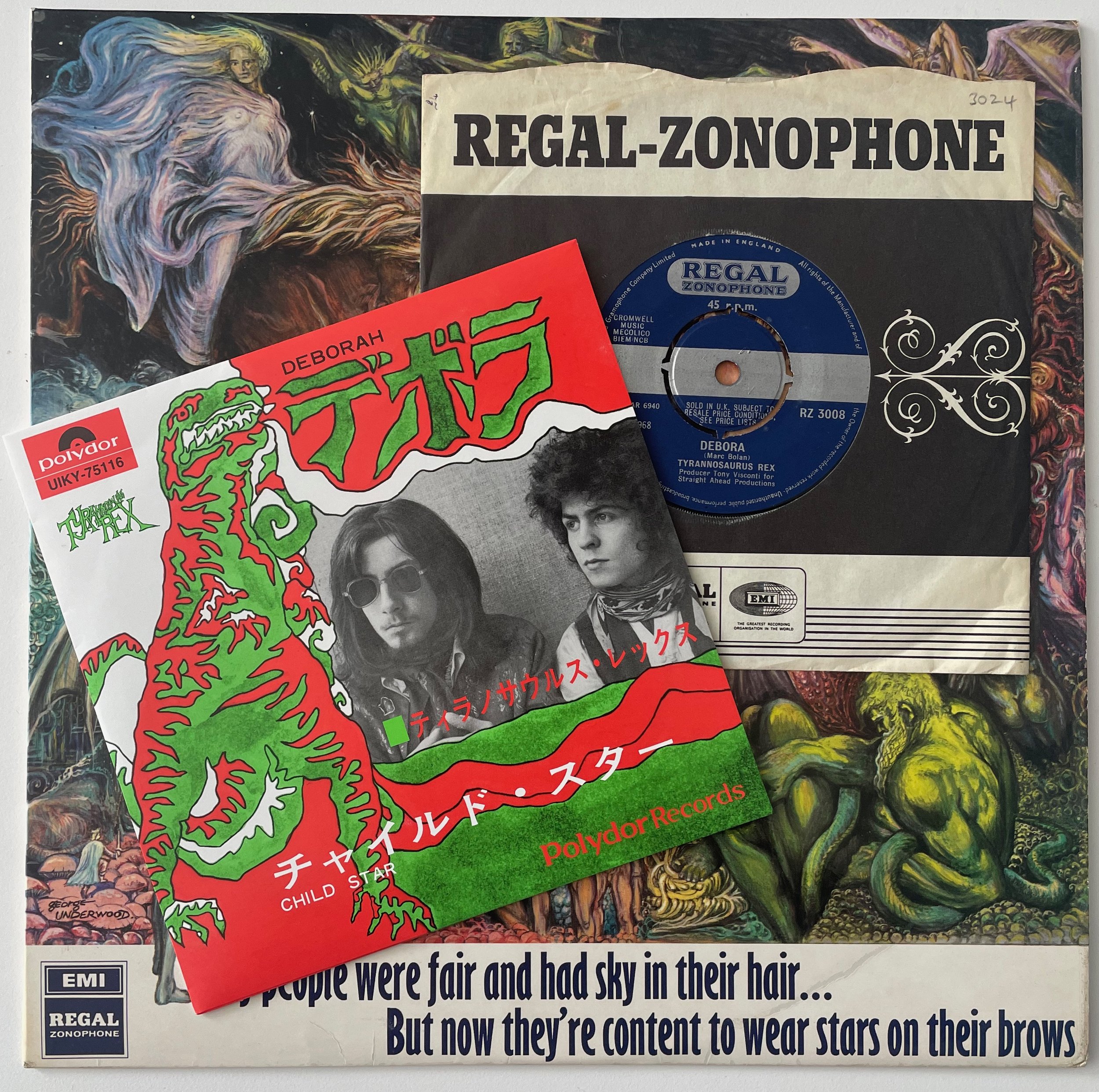

Tony Norman interviewed Marc for the October 24 issue with the emphasis on the moves he was making from the margins to the centre, from acoustic to electric, from the underground to the charts, with credibility still, as yet intact. The transition marked by his new, younger, audience of ‘Teenybop Heads’ – third-generation rock n’ rollers.

And for those who still had a bit of spare pocket money, Marc said his new label, Fly, are planning to issue not one but two best-of collections selling at the low price of 15/-

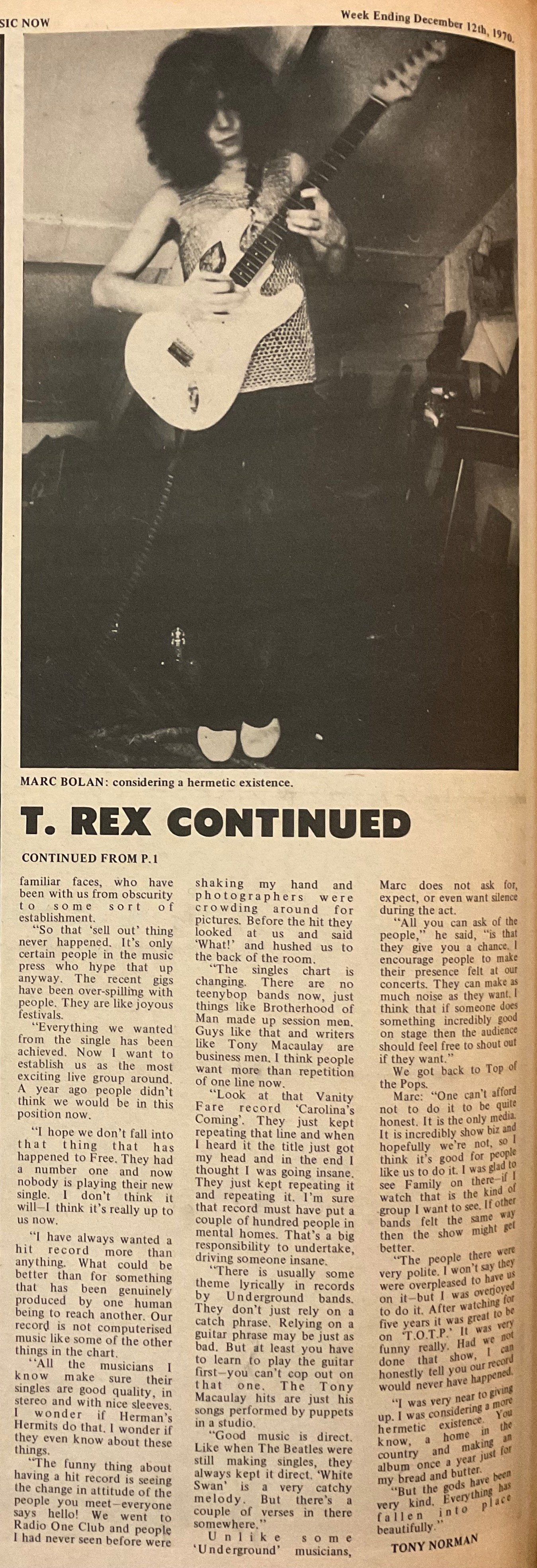

When things started to fall into place with the release of ‘Ride a White Swan’, TOTP exposure and the forthcoming album, Music Now put T. Rex on the cover (December 12) – the transition from the underground now all but complete (and in colour).

I have always wanted a hit record more than anything. What could be better than for something that has been genuinely produced by one human being to reach another. Our record is not computerised music like some of the other things in the chart. All the musicians know make sure their singles are good quality, in stereo and with nice sleeves. wonder if Herman's Hermits do that? I wonder if they even know about these things?

Marc then took aim at Tin Pan Alley songwriters, like Tony Macaulay, dismissing them as ‘business men’.

Look at that Vanity Fare record 'Carolina's Coming’. They just kept repeating that line and when I heard it the title just got in my head and in the end I thought l was going insane. They just kept repeating it and repeating it. I'm sure that record must have put a couple of hundred people in mental homes. That's a big responsibility to undertake, driving someone insane.

Marc’s sense of humour as sharp and as funny as ever, though Tony Macaulay didn’t appreciate it. He had his say in the following week’s issue:

T. Rex feel they can spout off about all this through having one hit to their credit. I'm only the songwriter, but I can go on ten times longer than any group because I can encompass every style or change as it comes. I have to think to myself, do I want instant recognition, which will probably last for a matter of weeks only, or alternatively, do I prefer to be always vaguely known to the public, but for ten times longer. . . I've never had to stoop to copying Mungo Jerry for ideas, and never resorted to two chords and thin microscopic voices. I don't need to put things in slots like T. Rex. All they produce is synthetic pop that's trying to be encompassed under an Underground roof. . . Anyway, T. Rex really were a little silly saying that . . . we manage them, or at least my company does!

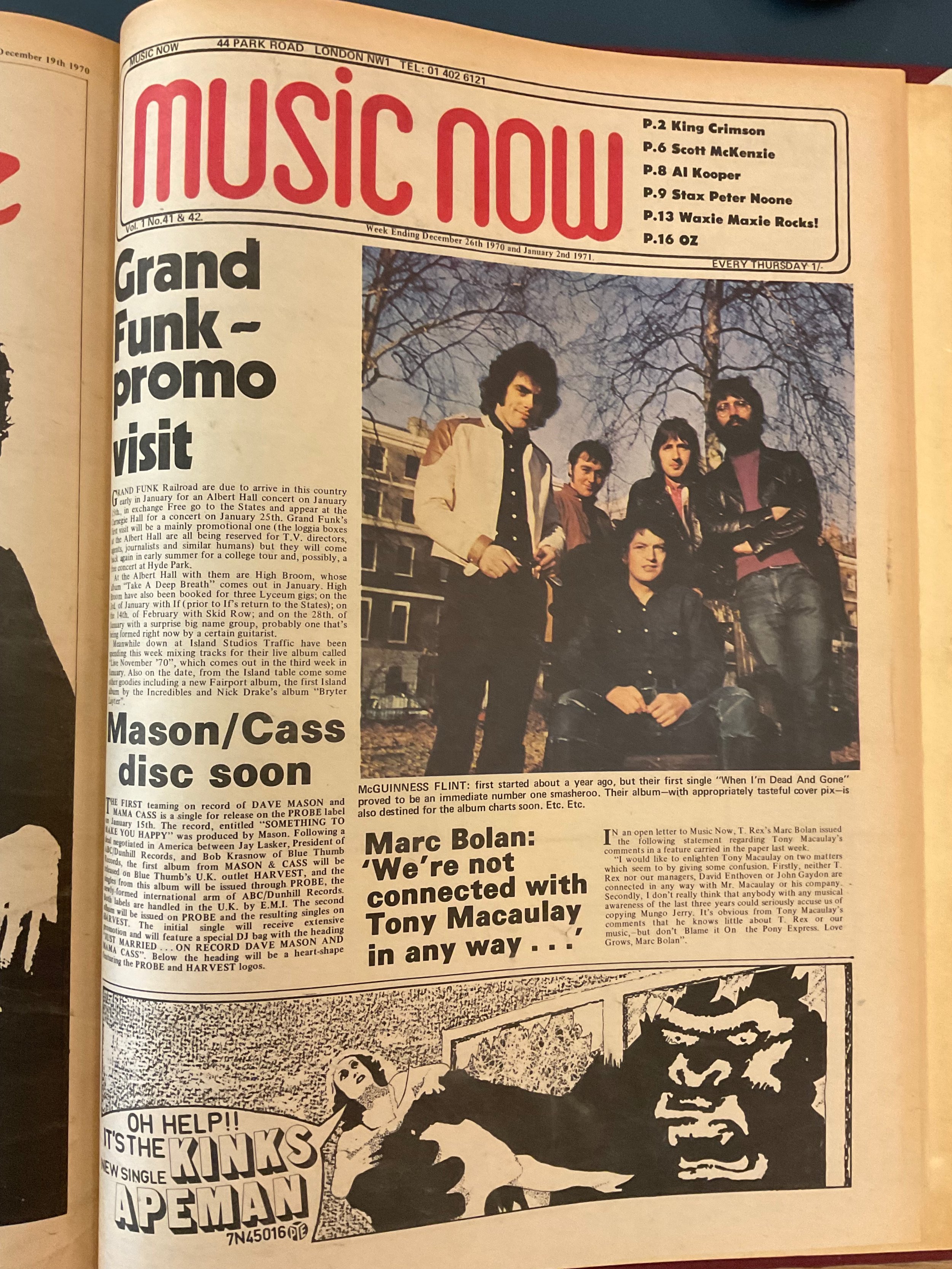

Marc continued the ‘dialogue’ on following week’s front page of Music Now:

I would like to enlighten Tony Macaulay on two matters which seem to by giving some confusion. Firstly, neither T. Rex nor our managers, David Enthoven or John Gaydon are connected in any way with Mr. Macaulay or his company. Secondly, I don't really think that anybody with any musical awareness of the last three years could seriously accuse us of copying Mungo Jerry. It's obvious from Tony Macaulay's comments that he knows little about T. Rex or our music, but don't Blame it On the Pony Express. Love Grows, Marc Bolan

See what I mean about his sense of humour . . . Love Grows

Summertime Blues in December

There was some confusion by Simon Stable over just which number on T. Rex’s bargain 3 track single was the lead number, ‘White Swan’, ‘Is It Love’ or ‘Summertime Blues’. Karen de Groot’s review of the single downplays, in fact doesn’t even mention, ‘White Swan’. A month earlier she had reviewed Dib Cochran and the Earwigs, though she didn’t much like it and had figured the band’s name was an alias – Beatles in drag – it did, however, all fit in with the current fascination with Eddie Cochran and the booming rock n’ roll revival. You can ask Pete Townshend if you don’t believe me . . . or Waxie Maxie even

Simon Stable, October 17 1970

September 26 1970

Waxie Maxie gets lyrical . . .

‘cos there ain’t no cure . . . .

. . . hard to beat.