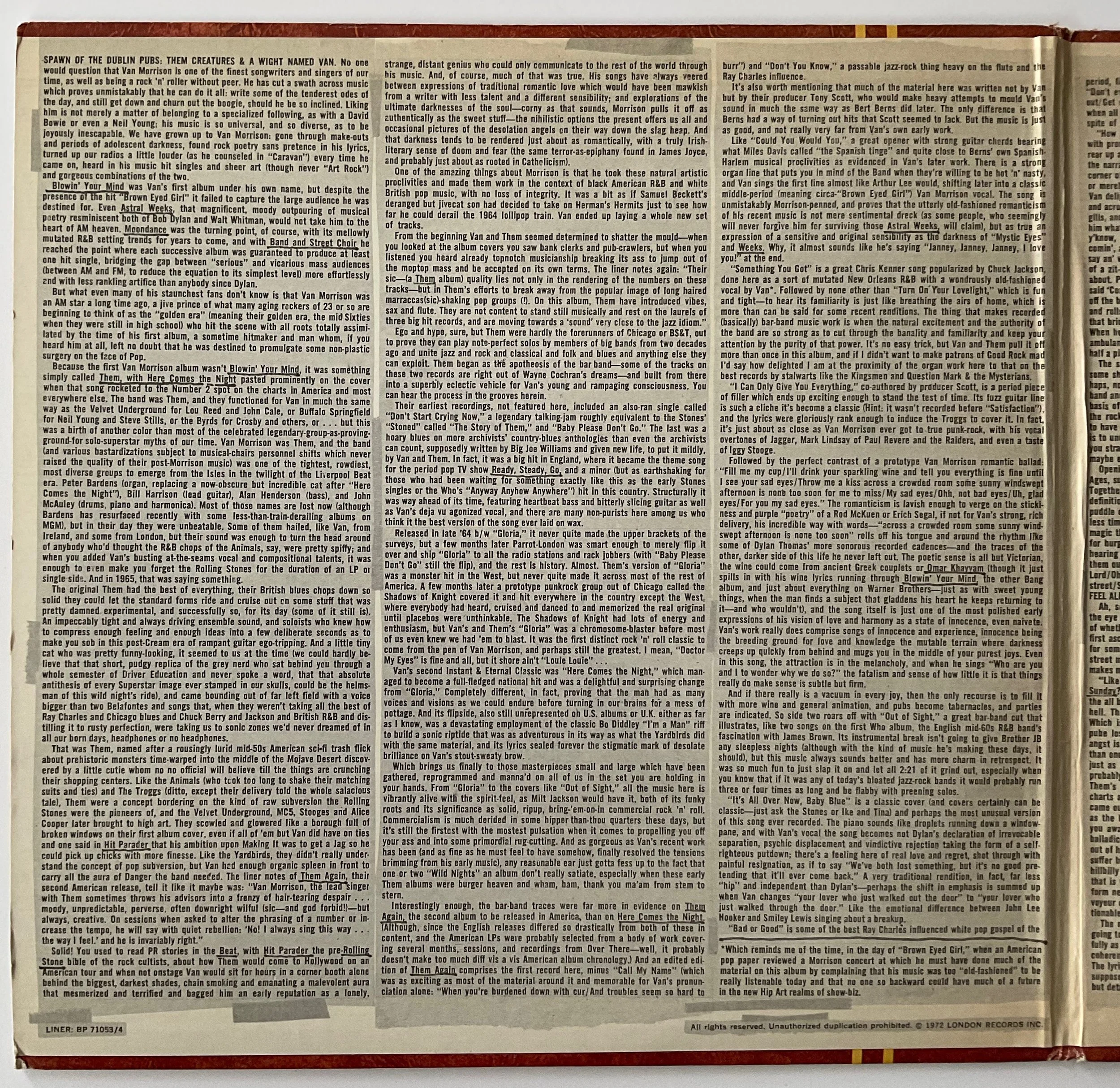

To mark my survey in Ugly Things #69 of the 1973 debates in the British press about the relative merits of THEM and Van Morrison, here’s the full text of the marvellous Lester Bangs’ sleeve notes for THEM Featuring Van Morrison (1972), all 6,500 words of ’em, which pretty much kick-started things . . . It’s Bangs, in full flow, at his very best

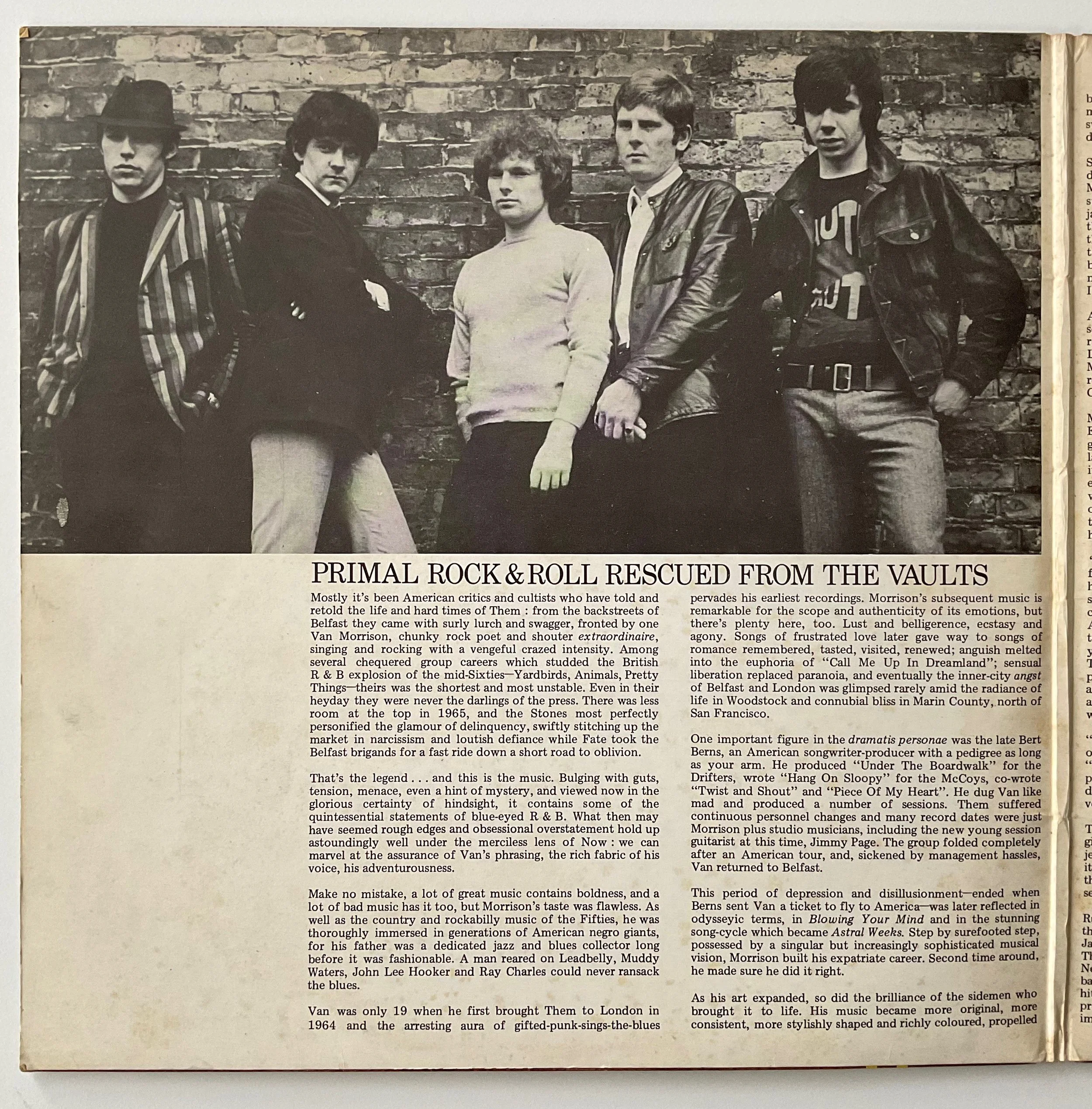

SPAWN OF THE DUBLIN PUBS: THEM CREATURES & A WIGHT NAMED VAN. No one would question that Van Morrison is one of the finest songwriters and singers of our time, as well as being a rock ’n’ roller without peer. He has cut a swath across music which proves unmistakably that he can do it all: write some of the tenderest odes of the day, and still get down and churn out the boogie, should he be so inclined. Liking him is not merely a matter of belonging to a specialized following, as with a David Bowie or even a Neil Young: his music is so universal, and so diverse, as to be joyously inescapable. We have grown up to Van Morrison: gone through make-outs and periods of adolescent darkness, found rock poetry sans pretence in his lyrics. turned up our radios a little louder (as he counseled in “Caravan” every time he came on, heard in his music hit singles and sheer art (though never “Art Rock”) and gorgeous combinations of the two.

Blowin' Your Mind was Van’s first album under his own name, but despite the presence of the hit “Bown Eyed Girl” it failed to capture the large audience he was destined for. Even Astral Weeks, that magnificent, moody outpouring of musical poetry reminiscent both of Bob Dylan and Walt Whitman, would not take him to the heart of AM heaven. Moondance was the turning point, of course, with its mellowly mutated R&B setting trends for years to come, and with Band and Street Choir he reached the point where each successive album was guaranteed to produce at least one hit single, bridging the gap between “serious” and vicarious mass audiences (between AM and FM, to reduce the equation to its simplest level) more effortlessly and with less rankling artifice than anybody since Dylan.

But what even many of his staunchest fans don’t know is that Van Morrison was an AM star a long time ago, a jive prince of what many aging rockers of 23 or so are beginning to think of as the “golden era” (meaning their golden era, the mid Sixties when they were still in high school) who hit the scene with all roots totally assimilated by the time of his first album, a sometime hitmaker and man whom, if you heard him at all, left no doubt that he was destined to promulgate some non-plastic surgery on the face of Pop.

Because the first Van Morrison album wasn’t Blowin’ Your Mind it was something simply called Them, with ‘Here Comes the Night’ pasted prominently on the cover when that song rocketed to the Number 2 spot on the charts in America and most everywhere else. The band was Them, and they functioned for Van in much the same way as the Velvet Underground for Lou Reed and John Cale, or Buffalo Springfield for Neil Young and Steve Stills, or the Byrds for Crosby and others, or . . . but this was a birth of another color than most of the celebrated legendary-group-as-proving-ground-for solo-superstar myths of our time. Van Morrison was Them, and the hand (and various bastardizations subject to musical-chairs personnel shifts which never raised the quality of their post-Morrison music) was one of the tightest, rowdiest, most diverse groups to emerge from the Isles in the twilight of the Liverpool Beat era. Peter Bardens (organ, replacing a now-obscure but incredible cat after “Here Comes the Night”), Bill Harrison lead guitar), Alan Henderson (bass), and John McAuley (drums, piano and harmonica). Most of those names are lost now (although Bardens has resurfaced recently with some less-than-train-derailing albums on MGM), but in their day they were unbeatable. Some of them hailed, like Van, from Ireland, and some from London, but their sound was enough to turn the head around of anybody who’d thought the R&B chops of the Animals, say, were pretty spiffy; and when you added Van’s busting at-the-seams vocal and compositional talents, it was enough to even make you forget the Rolling Stones for the duration of an LP or single side. And in 1965, that was saying something.

The original Them had the best of everything, their British blues chops down so solid they could let the standard forms ride and cruise out on some stuff that was pretty damned experimental, and successfully so, for its day (some of it still is). An impeccably tight and always driving ensemble sound, and soloists who knew how to compress enough feeling and enough ideas into a few deliberate seconds as to make you sob in this post-Cream era of rampant guitar ego-tripping. And a little tiny cat who was pretty funny-looking, it seemed to us at the time (we could hardly believe that that short, pudgy replica of the grey nerd who sat behind you through a whole semester of Driver Education and never spoke a word, that that absolute antithesis of every Superstar image ever stamped in our skulls, could be the helmsman of this wild night’s ride), and came bounding out of far left field with a voice bigger than two Belafontes and songs that, when they weren’t taking all the best of Ray Charles and Chicago blues and Chuck Berry and Jackson and British R&B and distilling it to rusty perfection, were taking us to sonic zones we’d never dreamed of in all our born days, headphones or no headphones.

Dave Marsh’s review of the album in Creem (December 1972): ‘Lester Bangs liner notes complement a package which is just trashy enough to be perfect. Bangs' commentary is so lucid and clear that any expansion on the songs is superfluous. With it. Them's recordings can be seen in both historical perspective and in the context of the career Van later carved for himself. It is easily the best thing I've ever read on Morrison. (If only Hot Rocks had had the same advantage .. .)’

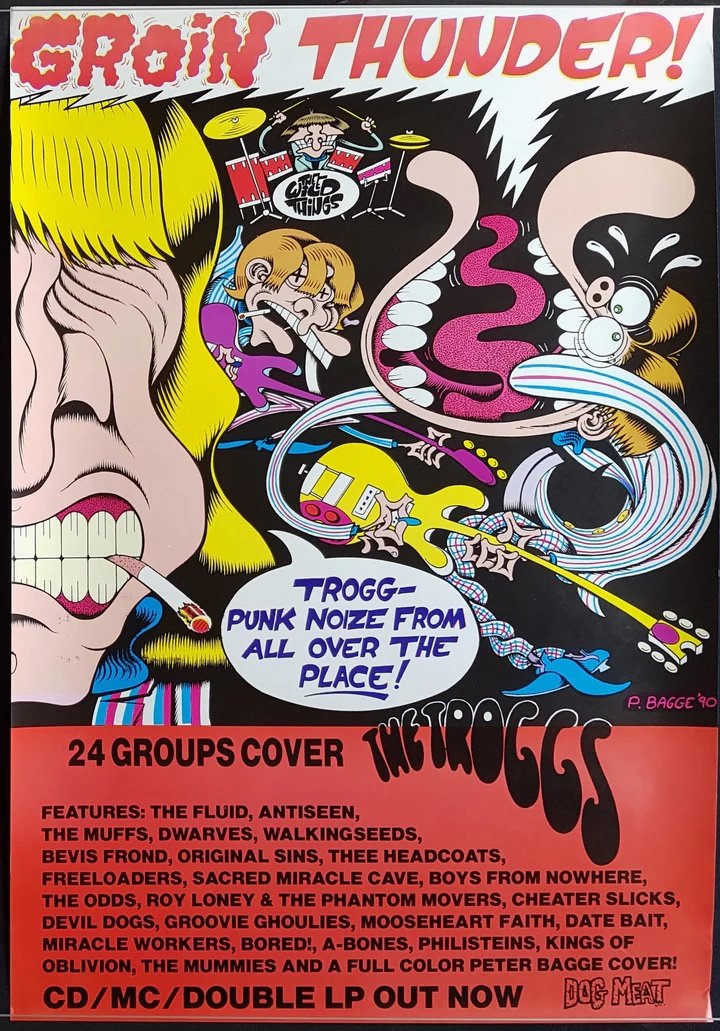

That was Them, named after a rousingly lurid mid-50s American sci-fi trash flick about prehistoric monsters time-warped into the middle of the Mojave Desert discovered by a little cutie whom no official will believe till the things are crunching their shopping centers. Like the Animals (who took too long to shake their matching suits and ties) and The Troggs (ditto, except their delivery told the whole salacious tale), Them were a concept bordering on the kind of raw subversion the Rolling Stones were the pioneers of, and the Velvet Underground, MC5, Stooges and Alice Cooper later brought to high art. They scowled and glowered like a borough full of broken windows on their first album cover, even if all of ’em but Van did have on ties and one said in Hit Parader that his ambition upon Making It was to get a Jag so he could pick up chicks with more finesse. Like the Yardbirds, they didn't really understand the concept of pop subversion, but Van had enough organic spleen in front to carry all the aura of Danger the band needed. The liner notes of Them Again, their second American release, tell it like it maybe was: “Van Morrison, the lead singer with Them sometimes throws his advisors info a frenzy of hair-tearing despair . . . moody, unpredictable, perverse, often downright wilful (and god forbid!) – but always, creative. On sessions when asked to alter the phrasing of a number or increase the tempo, he will say with quiet rebellion: ‘No! I always sing this way . . . the way I feel,’ and he is invariably right.”

Solid! You used to read PR stories in the Beat, with Hit Parader the pre-Rolling Stone bible of the rock cultists, about how Them would come to Hollywood on an American tour and when not onstage Van would sit for hours in a corner booth alone behind the biggest, darkest shades, chain smoking and emanating a malevolent aura that mesmerized and terrified and bagged him an early reputation as a lonely, strange, distant genius who could only communicate to the rest of the world through his music. And, of course, much of that was true, His songs have always veered between expressions of traditional romantic love which would have been mawkish from a writer with less talent and a different sensibility; and explorations of the ultimate darknesses of the soul – corny as that sounds, Morrison pulls it off as authentically as the sweet stuff – the nihilistic options the present offers us all and occasional pictures of the desolation angels on their way down the slag heap. And that darkness tends to be rendered just about as romantically, with a truly Irish-literary sense of doom and fear (the same terror-as-epiphany found in James Joyce, and probably just about as rooted in Catholicism).

One of the amazing things about Morrison is that he took these natural artistic proclivities and made them work In the context of black American R&B and white British pop music, with no loss of integrity. It was a bit as if Samuel Beckett’s deranged but jivecat son had decided to take on Herman’s Hermits just to see how far he could derail the 1964 lollipop train. Van ended up laying a whole new set of tracks,

From the beginning Van and Them seemed determined to shatter the mould – when you looked at the album covers you saw bank clerks and pub-crawlers, but when you listened you heard already topnotch musicianship breaking its ass to jump out of the moptop mass and be accepted on its own terms. The liner notes again: Their “quality lies not only in the rendering of the numbers on these tracks – but in Them’s efforts to break away from the popular image of long haired maracas-shaking pop groups (!). On this album, Them have introduced vibes, sax and flute. They are not content to stand still musically and rest on the laurels of three big hit records, and are moving towards a ‘sound’ very close to the jazz idiom.”

Ego and hype, sure, but Them were hardly the forerunners of Chicago or BS&T, out to prove they can play note-perfect solos by members of big bands from two decades ago and unite jazz and rock and classical and folk and blues and anything else they can exploit. Them began as the apotheosis of the bar band – some of the tracks on these two records are right out of Wayne Cochran’s dreams – and built from there into a superbly eclectic vehicle for Van’s young and rampaging consciousness. You can hear the process in the grooves herein.

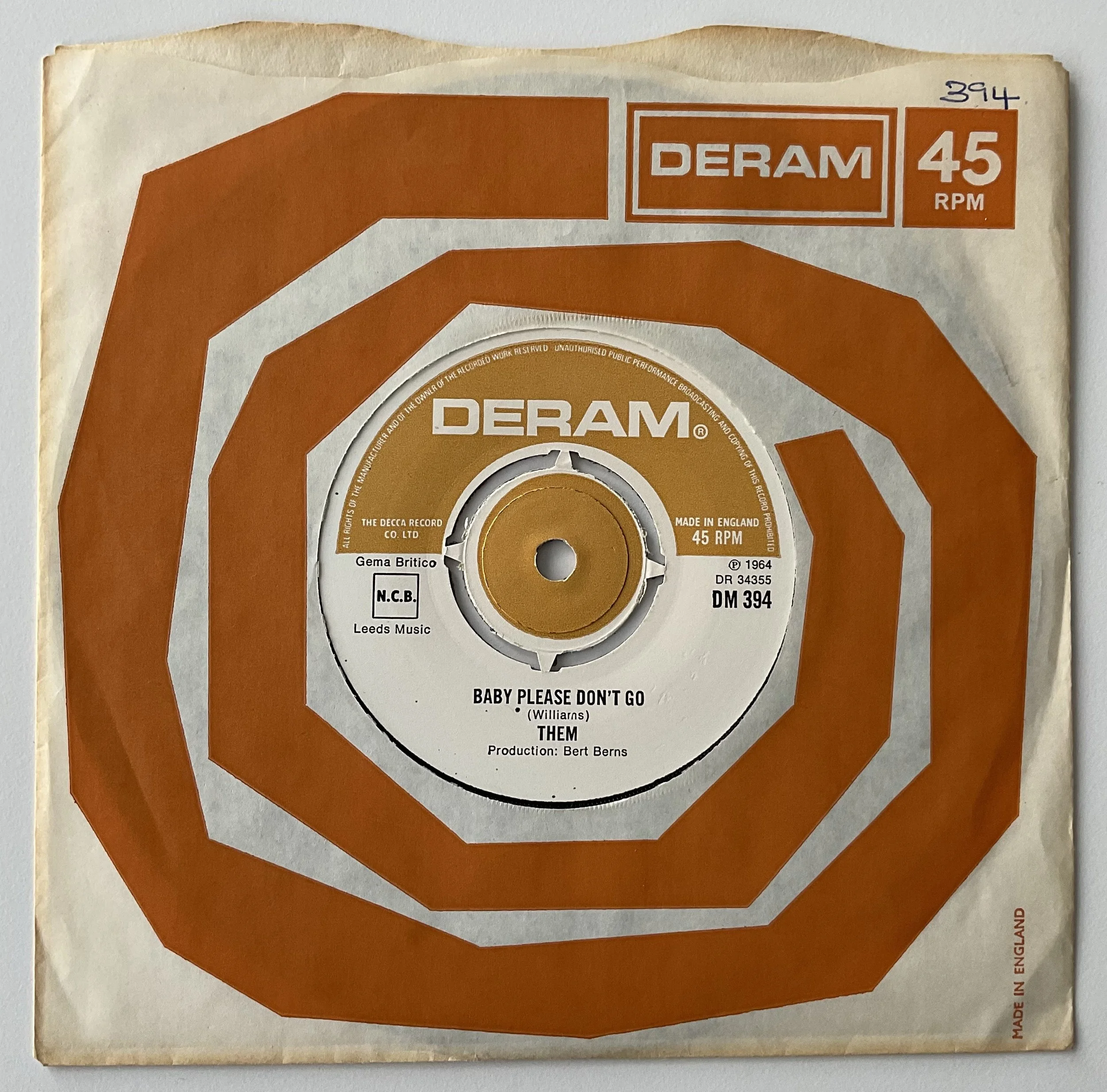

Their earliest recordings, not featured here, included an also-ran single called “Don't Start Crying Now,” a legendary talking-jam roughly equivalent to the Stones’ “Stoned” called “The Story of Them,” and “Baby Please Don’t Go.” The last was a hoary blues on more archivists’ country-blues anthologies than even the archivists can count, supposedly written by Big Joe Williams and given new life, to put it mildly, by Van and Them. In fact, it was a big hit in England, where it became the theme song for the period pop TV show Ready, Steady, Go, and a minor (but as earthshaking for those who had been waiting for something exactly like this as the early Stones singles or the Who’s “Anyway Anyhow Anywhere”) hit in this country. Structurally it was way ahead of its time, featuring heartbeat bass and bitterly slicing guitar as well as Van's deja vu agonized vocal, and there are many non-purists here among us who think it the best version of the song ever laid on wax.

Released In late ’64 b/w “Gloria,” it never quite made the upper brackets of the surveys, but a few months later Parrot-London was smart enough to merely flip it over and ship “Gloria” to all the radio stations and rack jobbers (with “Baby Please Don't Go” still the flip), and the rest is history. Almost. Them’s version of “Gloria” was a monster hit In the West, but never quite made it across most of the rest of America. A few months later a prototype punkrock group out of Chicago called the Shadows of Knight covered it and hit everywhere in the country except the West, where everybody had heard, cruised and danced to and memorized the real original until placebos were unthinkable. The Shadows of Knight had lots of energy and enthusiasm, but Van’s and Them’s “Gloria” was a chromosome-blaster before most of us even knew we had ’em to blast. It was the first distinct rock ’n’ roll classic to come from the pen of Van Morrison, and perhaps still the greatest. I mean, “Doctor My Eyes” is fine and all, but it shore ain’t “Louie Louie” . . .

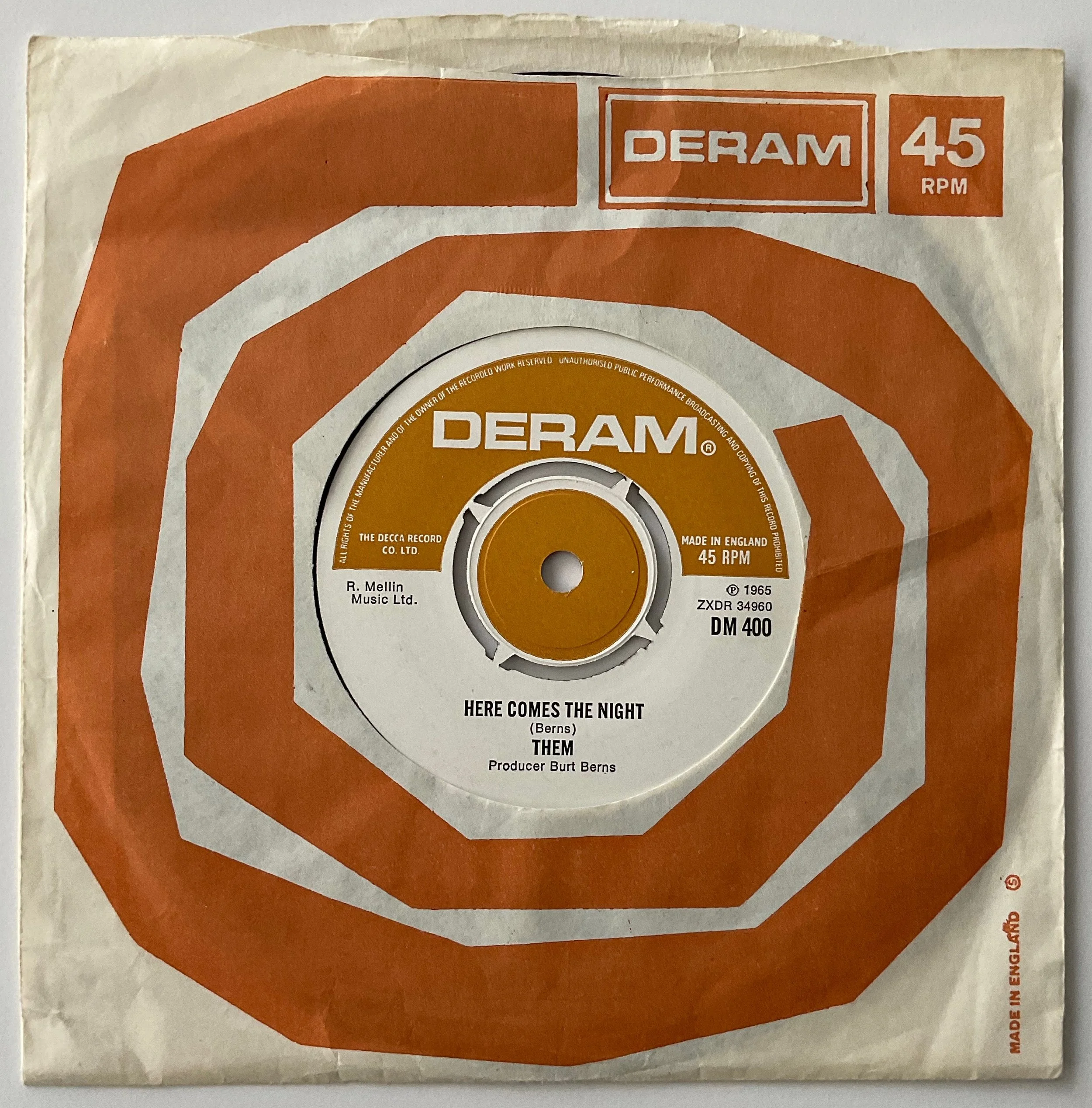

Van’s second Instant & Eternal Classic was “Here Comes the Night,” which managed to become a full-fledged national hit and was a delightful and surprising change from “Gloria.” Completely different, in fact, proving that the man had as many voices and visions as we could endure before turning in our brains for a mess of pottage. And its flipside [“All For Myself”], also still unrepresented on U.S. albums or U.K. either as far as I know, was a devastating employment of the classic Bo Diddley “I’m a Man” riff to build a sonic riptide that was as adventurous in its way as what the Yardbirds did with the same material, and its lyrics sealed forever the stigmatic mark of desolate brilliance on Van’s stout-sweaty brow,

Which brings us finally to those masterpieces small and large which have been gathered, reprogrammed and manna'd on all of us in the set you are holding in your hands. From “Gloria” to the covers like “Out of Sight,” all the music here is vibrantly alive with the spirit-feel, as Milt Jackson would have it, both of its funky roots and its significance as solid, ripup, bring-’em-on-in commercial rock ’n’ roll. Commercialism is much derided in some hipper than-thou quarters these days, but it’s still the firstest with the mostest pulsation when it comes to propelling you off your ass and into some primordial rug-cutting. And as gorgeous as Van’s recent work has been (and as fine as he must feel to have somehow, finally resolved the tensions brimming from his early music), any reasonable ear just gotta fess up to the fact that one or two “Wild Nights” an album don’t really satiate, especially when these early Them albums were burger heaven and wham, bam, thank you ma’am from stem to stern.

Interestingly enough, the bar-band traces were for more in evidence on Them Again,

the second album to be released in America, than on Here Comes the Night. Although, since the English releases differed so drastically From both of these in content, and the American LPs were probably selected from a body of work covering several months, sessions, and recordings from Over There – well, it probably doesn’t make too much diff vis a vis American album chronology.) And an edited edition of Them Again comprises the first record here, minus “Call My Name” (which was as exciting as most of the material around it and memorable for Van's pronunciation alone: "When you're burdened down with cur/And troubles seem so hard to burr”) and “Don’t You Know,” a passable jazz-rock thing heavy on the flute and Ray Charles influence.

It’s also worth mentioning that much of the material here was written not by Van but by their producer Tony Scott, who would make heavy attempts to mould Van’s sound in much the same way as Bert Berns did later. The only difference is that Berns had a way of turning out hits that Scott seemed to lack. But the music is just as good, and not really very far from Van’s own early work.

Like “Could You Would You,” a great opener with strong guitar chords bearing what Miles Davis called “the Spanish tinge” and quite close to Berns’ own Spanish Harlem musical proclivities as evidenced in Van’s later work. There is a strong organ line that puts you in mind of the Band when they’re willing to be hot ’n’ nasty, and Van sings the first line almost like Arthur Lee would, shifting later into a classic middle-period (meaning circa–“Brown Eyed Girl”) Van Morrison vocal. The song is unmistakably Morrison-penned, and proves that the utterly old-fashioned romanticism of his recent music is not mere sentimental dreck (as some people, who seemingly will never forgive him for surviving those Astral Weeks will claim), but as true an expression of a sensitive and original sensibility as the darkness of “Mystic Eyes” and Weeks. Why, it almost sounds like he’s saying “Janney, Janney, Janney, I love you!” at the end.

“Something You Got” is a great Chris Kenner song popularized by Chuck Jackson, done here as a sort of mutated New Orleans R&B with a wondrously old-fashioned vocal by Van.[i] Followed by none other than “Turn On' Your Lovelight,” which is fun and tight – to hear its familiarity is just like breathing the airs of home, which is more than can be said for some recent renditions. The thing that makes recorded (basically) bar-band music work is when the natural excitement and the authority of the band are so strong as to cut through the banality and familiarity and keep your attention by the purity of that power. It’s no easy trick, but Van and Them pull it off more than once in this album, and if I didn’t want to make patrons of Good Rock mad I’d say how delighted I am at the proximity of the organ work here to that on the best records by stalwarts like the Kingsmen and Question Mark & the Mysterians.

“I Can Only Give You Everything,” co-authored by producer Scott, is a period piece of filler which ends up exciting enough to stand the test of time. Its fuzz guitar line is such a cliche it’s become a classic (Hint: it wasn’t recorded before “Satisfaction” and the lyrics were gloriously rank enough to induce the Troggs to cover it. In fact, it’s just about as close as Van Morrison ever got to true punk-rock, with his vocal overtones of Jagger, Mark Lindsay of Paul Revere and the Raiders, and even a taste of Iggy Stooge.

Followed by the perfect contrast of a prototype Van Morrison romantic ballad: “Fill me my cup/I’ll drink your sparkling wine and tell you everything is fine until I see your sad eyes/Throw me a kiss across a crowded room some sunny windswept afternoon is none too soon for me to miss/My sad eyes/Ohh, not bad eyes/Uh, glad eyes/For you my sad eyes.” The romanticism is lavish enough to verge on the stickiness and purple “poetry” of a Rod McKuen or Erich Segal, if not for Van’s strong, rich delivery, his incredible way with words – “across a crowded room some sunny windswept afternoon is none too soon” rolls off his tongue and around the rhythm like some of Dylan Thomas’ more sonorous recorded cadences – and the traces of the other, darker side of this life he never left out. The poetic sense is all but Victorian, the wine could come from ancient Greek couplets or Omar Khayyam (though it just spills in with his wine lyrics running through Blowin’ Your Mind, the other Bang album, and just about everything on Warner Brothers – just as with sweet young things, when the man finds a subject that gladdens his heart he keeps returning to it – and who wouldn’t), and the song itself is just one of the most polished early expressions of his vision of love and harmony as a state of innocence, even naivete. Van’s work really does comprise songs of innocence and experience, innocence being the breeding ground for love and knowledge the mutable terrain where darkness creeps up quickly from behind and mugs you in the middle of your purest joys. Even in this song, the attraction is in the melancholy, and when he sings “Who are you and I to wonder why we do so?” the fatalism and sense of how little it is that things really do make sense is subtle but firm.

[i] Which reminds me of the time, in the day of “Brown Eyed Girl” when an American pop paper reviewed a Morrison concert at which he must have done much of the material on this album by complaining that his music was too “old-fashioned” to be really listenable today and that no one so backward could have much of a future In the new Hip Art realms of show-biz.

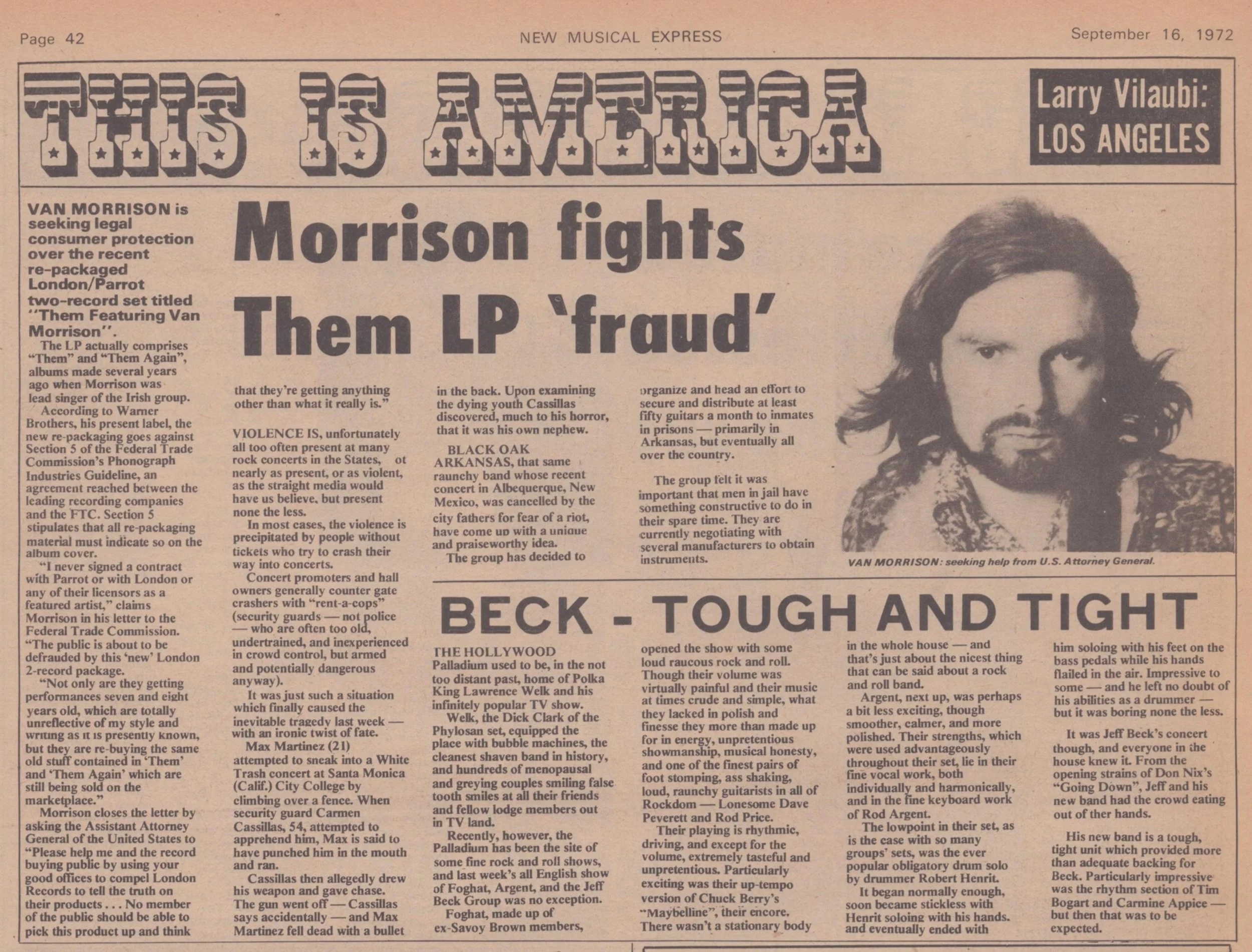

Van was not best pleased with the album . . . of course he wasn’t . . .New Musical Express (September 16 1972)

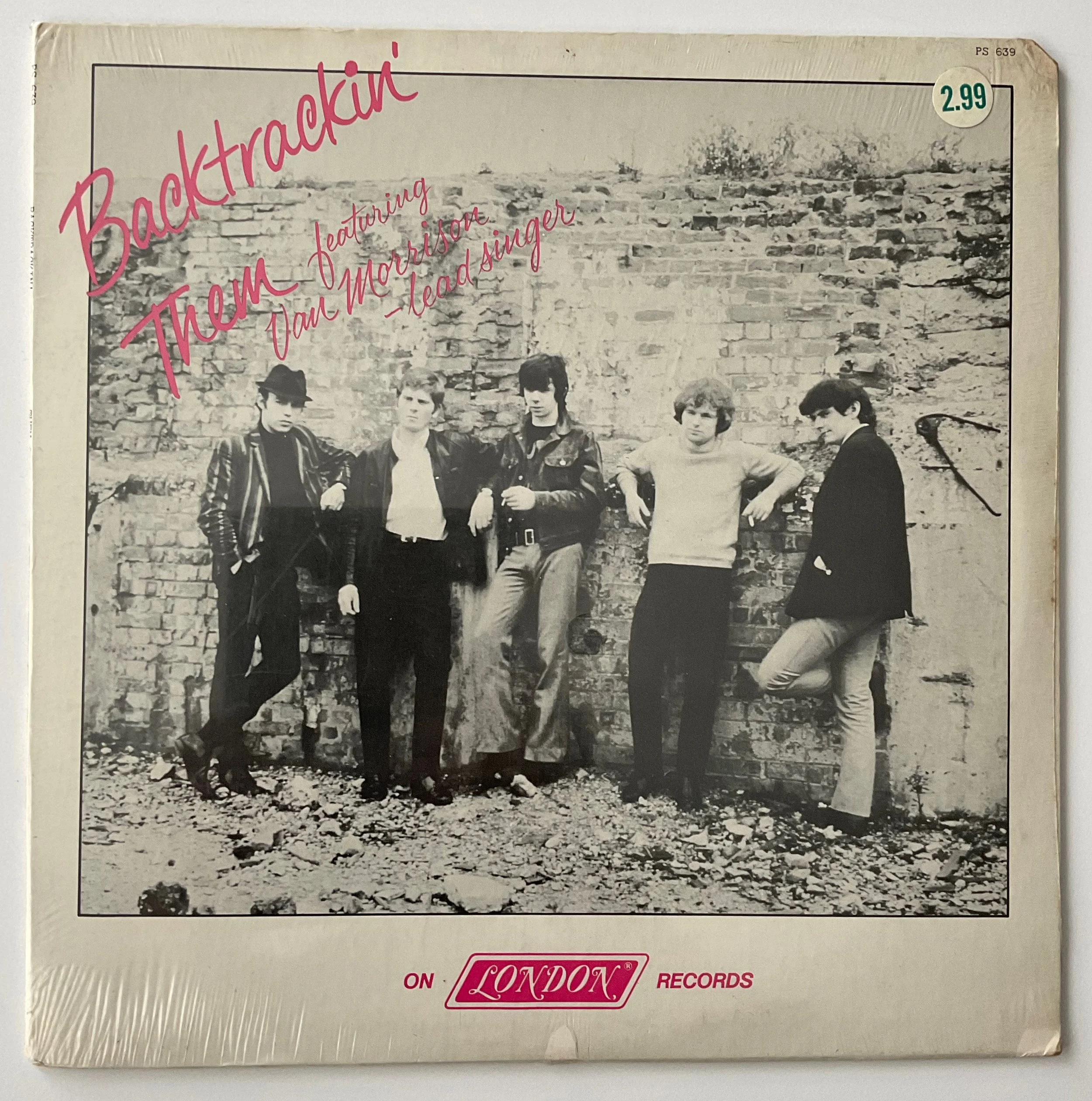

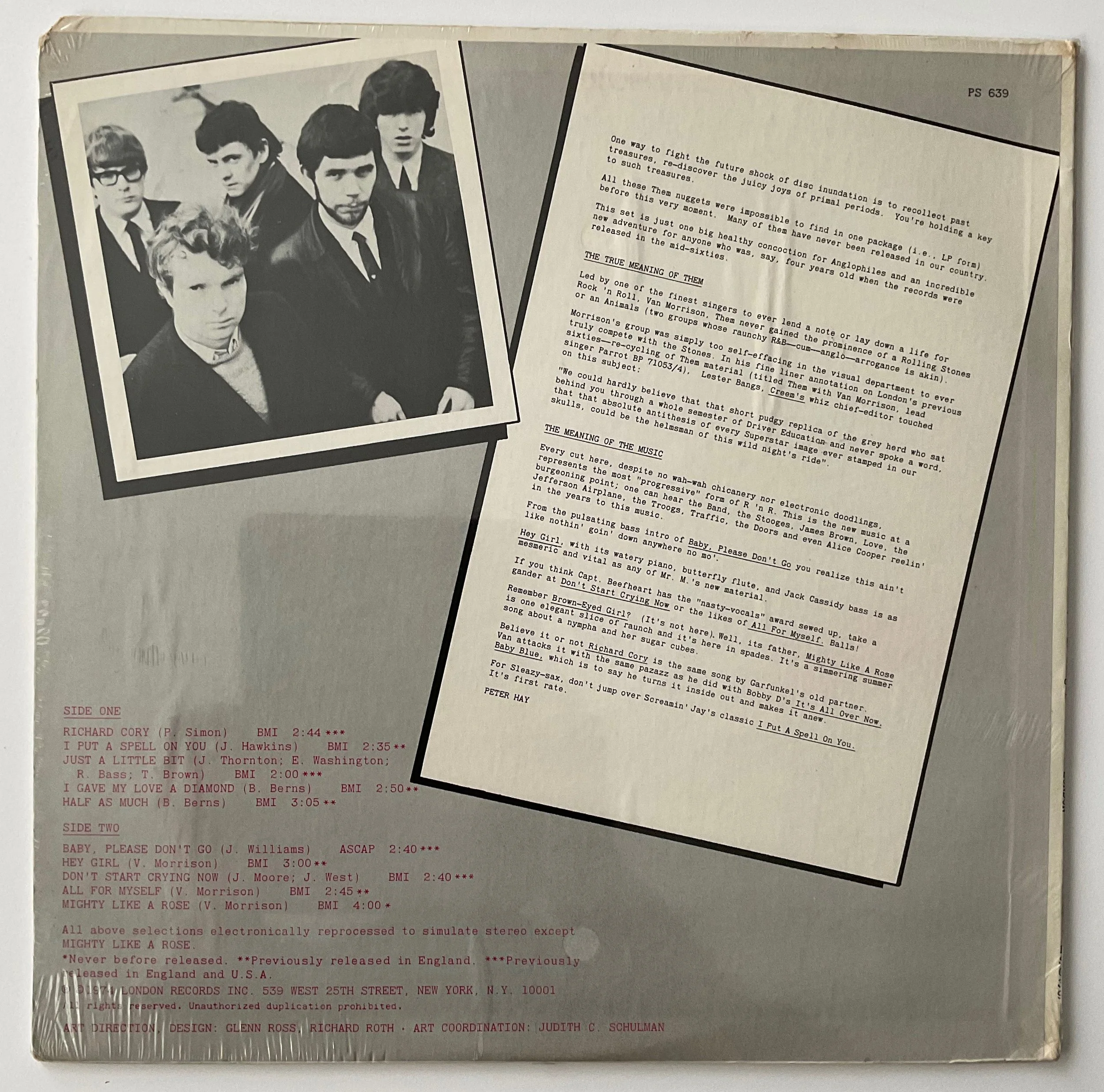

A 1974 collection that pulled together many of the more significant omissions from the double-album and the first release of ‘Mighty Like A Rose’

And if there really is a vacuum in every joy, then the only recourse is to fill it with more wine and general animation, and pubs become tabernacles, and parties are indicated. So side two roars off with “Out of Sight,” a great bar-band cut that illustrates, like two songs on the first Who album, the English mid-60s R&B band's fascination with James Brown. Its instrumental break isn’t going to give Brother JB any sleepless nights (although with the kind of music he's making these days, it should), but this music always sounds better and has more charm in retrospect. It was so much fun to just slap it on and let all 2:21 of it grind out, especially when you know that if it was any of today’s bloated jazz-rock bands it would probably run three or four times as long and be flabby with preening solos.

“It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” is a classic cover (and covers certainly can be classic – just ask the Stones or Ike and Tina) and perhaps the most unusual version of this song ever recorded. The piano sounds like droplets running down a windowpane, and with Van’s vocal the song becomes not Dylan’s declaration of irrevocable separation, psychic displacement and vindictive rejection taking the form of a self-righteous putdown; there’s a feeling here of real love and regret, shot through with painful resignation, as if to say “We’ve both lost something, but it’s no good pretending that it’ll ever come back.” A very traditional rendition, in fact, far less “hip” and independent than Dylan’s – perhaps the shift in emphasis is summed up when Van changes “your lover who just walked out the door” to “your lover who just walked through the door.” Like the emotional difference between John Lee Hooker and Smiley Lewis singing about a breakup.

“Bad or Good” is some of the best Ray Charles influenced white pop gospel of the period, finding a soulful strength in absolute fatalism just as Gospel always has: “Don’t even have to say one word/lt ain’t nothin’ that we’ve seen or heard/Get out/Get out/Jump and shout/Then you know what it’s all about . . . Gotta hold on when all is good/Make out like all is fine/ Gotta let it happen/Bad or good.” And, in spite of all obvious influences, unmistakably a Morrison original—lyrics don’t lie.

“How Long Baby" takes similar musical strains deeper into a soul blues ballad with prominent Pop Staples type Delta echo guitar, leaving Van no recourse but to rear up and ride the side out shouting “Bring ’Em On In.” Raveup time, enhanced by the narrative style which appears in many of his songs. When not exploring a bleak corner of some urban scene with a novelist’s attention to detail : “Madame George”), or merely reflecting the joys his wife and child have brought him, (Tupelo Honey), Van delights in moving on, down the sidewalk, across the steet, from here to there and across the water. I saw him once on American Bandstand in 1966, stewed to the gills, and when Dick Clark: tried to conduct his usual Barbie Doll interview and asked him what he’d been doing lately. Van drooled a few seconds of garble and "WuhhhIll, y'know, man, l just like, I just walk on down the street, right along, and keep on comin’, and come by some cafes, and see somebody or whoever, and they say and I say an’ we sit and drink an’ then walk on . . .” Clark hustled him off camera in favor of a zit-creme commercial pronto, but that reply, essentially, is what this song is about. Places: “I was walkin’ down by Queensway/When I met a friend of mine/He said ‘Come on back, back to my pad/We can have a good time’” and “When I stepped off the boat and I walked upon the dry land/Slowly!/To the carpark/And I jumped in” and rolls off down the road once more, reeling in and out of a great scat section that bridges into a blustery 50s sax solo. Off the wall and up the avenue of dreams. When he sez “out of my mind!” it ain’t like Neil Young fainting in the back of an ambulance, it’s jumping loose enough to smash your head against the wall and pour half a pint of Bordeaux on the wound! Shout don’t stop!

The second record, which corresponds except for two dropped songs again and some shifts in sequence to the Here Comes the Night album, is less raucous, perhaps, not so pub-loose, but better produced and a far more potent statement by a band and an artist beginning to feel the heady extent of their powers. Heavier on the basis of being almost all Morrison originals alone, it is really a landmark album in the rock ’n’ roll of the Sixties that nobody who cares about the music (or wants to have their skull pulverized now and then) should be without. To say it’s essential is to understate its importance – it’s more than history, it’s timeless jive that drives you straight out of your mind and into your body, as John Sinclair would have it, and maybe even clear up the wall if visceral music ain’t yer cup of meat.

Opening with the showstopper of them all, “Gloria.” This, folks, is the Rock of Ages, sure as “Long Tall Sally” or “Sweet Little Sixteen” or “Let's Spend the Night together” or maybe even “Are You Ready.” It’s a demonstrative self-contained definition of rock ’n’ roll that will have you moving or shrivel you into a Librium puddle of MOR drool. It’ll be heard as long as rock ’n’ roll endures, and never sound less timely than it did the day they cut it. A paraplegic could dance to it – it has the magic that’ll set you free like few songs by the Spoonful or anybody else. Cruising for burgers to it in 1965 was more cosmic than any acid trip, and after even one hearing no one could ever forget those creaming lyrics and how seethingly Van spat them out: “She comes around here/Just about midnight/ She makes me feel so good, Lord/Ohh, I wanna say she make me feel all right/Cause she walkin’ down my street/She knock upon my door/And then she comes to my room/Man, she make me FEEL ALRIGHT!!!!!”

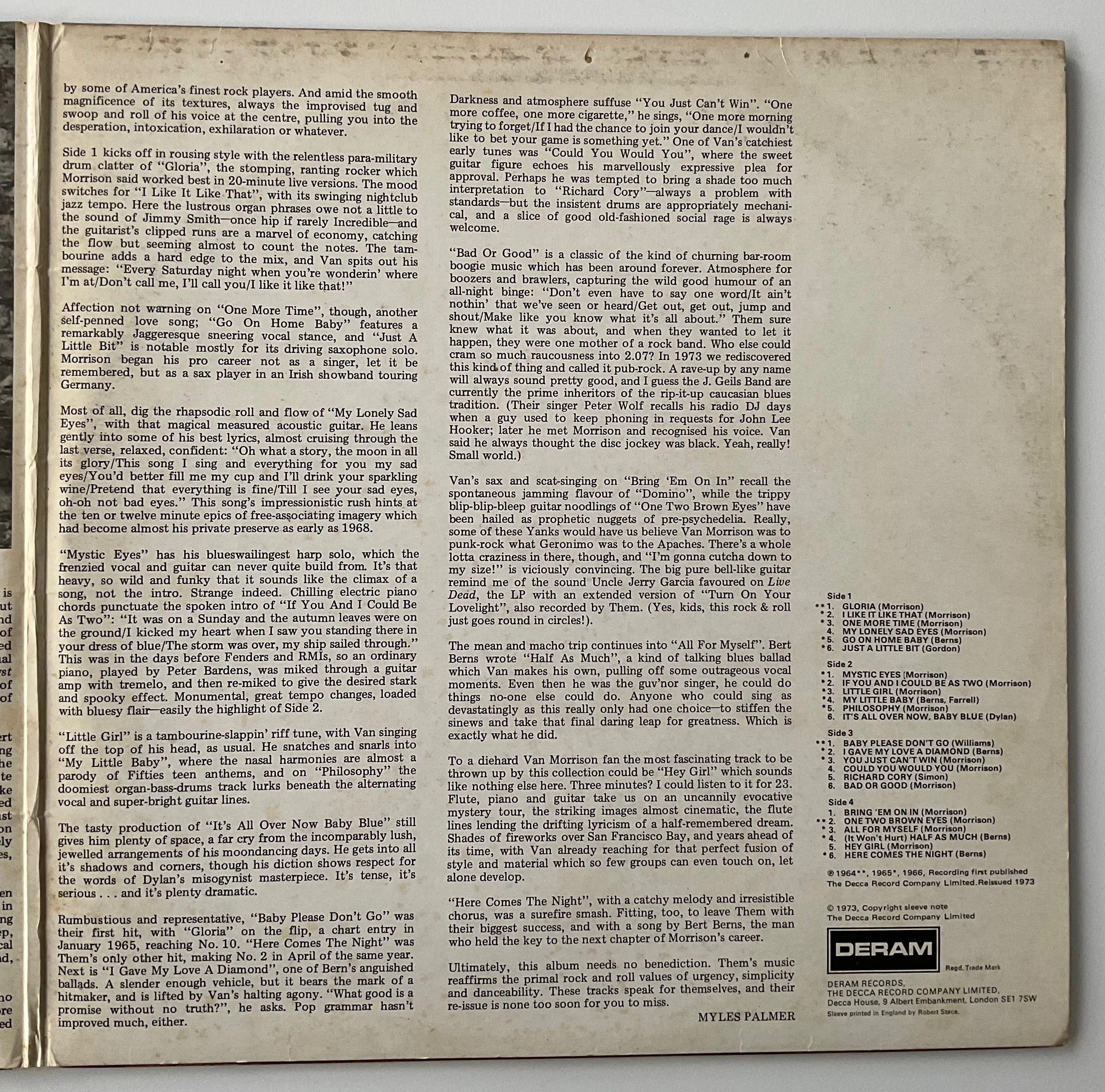

Myles Palmer’s notes for the British version of ‘Featuring Van Morrison’: ‘Ultimately this album needs no bendiction. Them’s music reaffirms the primal rock and roll values of urgency, simplicity and danceability’

Ah, sexism! The joys of that utterly apolitical horniness has brought a tear to the eye of many a reminiscing campus revolutionary as he wrestles with the problem of whether he’s got a right to ask his girl to shave her legs! In the days of “Gloria’s” first ascendance, people sweated other neuroses. Just dig “Here Comes the Night” for some real sick sentiments: “I can see right out my window walkin’ down the street my girl with another guy/His arm around her like it used to be with me. oh it makes me wanta cry!”

“Like it used to be with me” (“his arm around her”)? What is this, Sunday Bloodly Sunday? Nahh, it’s just the remarkable rhyme scheme of this song which pulls off the all but unparalleled achievement of being simultaneously perfect and awkward as hell. The words seem to tumble backwards over each other in true spazz spew. Which is absolutely appropriate, since the song was about being a poor awkward pube losing his long dream and short steady to some strutting BMOC [Big Man On Campus]. Adolescent angst is technicolor and Todd-A0, and if we all came clean who has not mused more than once ’twixt twelve and twenty or even after “Wonder what is wrong with me?”, just as Van does here. If you went to high school with this song, like I did, you probably lived it too. If not, you may even be living it now. In any case, it was Them’s first solid national hit on this side of the pond, shooting straight up the charts and nudging into the number two spot only because the new Beatles single came out at the same time. And despite being a superhit, it’s a totally bizarre song, as the lyrics attest. The way Van barks “Wow, here it comes!” is enough to keep you awake nights, and the structure is unusual, changing from a vaguely Latinish balladic lament (the Bert Berns touch, again; the man never quite got the hot sauce out of his ears after his “Twist & Shout” conquered the world, and though Van didn’t suffer by it, it did make some of his music fairly predictable) into a sort of wierdo hillbilly roundelay, which is where the gawky lyrics quoted came in. There’s no doubt that is was as much a rock ’n’ roll classic in its way as “Gloria,” if destined by Its form never to become such a standard, and even ends with the protagonist playing voyeur outside the window where the objects of his jealousy carry on in every unmentionable way his fertile pube brain can dream up.

The next song is, simply, one of the most powerful pieces of music you are ever going to have the opportunity to hear. "Mystic Eyes" was an all-time brain blitz that’s fully as devastating today as it ever was; vicious, utterly nihilistic barrages of sound, coherently performed and pristinely recorded, making the rage that much more vivid. The lyrics are cornball but terrifying (an early liner says that the song was originally supposed to be instrumental and they were adlibbed in the studio, which is believable but detracts not a whit from their impact), and the guitar lines are as razor edged as anything Mike Bloomfield did on Highway 61 Revisited or the first Paul Butterfield album (both of which came out after this, by the way . “Mystic Eyes” is an exercise in pure adrenalin frenzy, Van Morrison’s darker side at its most ferociously anguished. And if all that wasn’t enough, it also contains one of the best harp solos (almost certainly by Van) ever recorded. When he finally returns to his harp after the vocal it is with a savage snarling chomp!, as of a barracuda biting down.

All of which makes “Don’t Look Back,” a bar-band ballad harkening back to the other album, a welcome relief. Originally a John Lee Hooker song, it’s not as sentimentally innocuous as it might at first appear. After all, Dylan named a movie after it. And even if that’s not really true, it’s a beautiful composition and performance with an unforced message that becomes neither preachy nor sappy. When he says, “Those days are gone,” he means no Gee-whiz but exactly, strongly what he says: “Stop dreaming and live on in the future/Darlin’, don't look back.” Which seems doubly applicable today, even if the appearance of an album like this one is evidence of the uses and vitality of the past.

“Little Girl”. Ah, nymphomania! Well, not necessarily, but there comes a point where the honest chronicler must deal with certain recurrent themes, as I said before, in Van’s oeuvre, and this is the cookingest mutation of “Good Morning Little School Girl” this side of Vladimir Nabokov. It has a great chugging construction, and voyeurism of so poetic a turn as to make a grown lecher cry: “Saw you from my window” – “Cypress Avenue,” here we come – and a dreamscape middle section: “In miles and miles of golden sand/Walkin’, talkin’, hand in hand”. Leading to a final lust-crazed raveup. Another classic – “Sweet Little 16” was a stunner, but you shoulda seen her little sister. Van did.

“One More Time” links generically to “Don’t Look Back” and “How long Baby” as blues ballad and functions as throwforward to his current stuff: “It won’t be long till I’m comin’ on home/Gonna get you in my arms and make love to you, darlin’, just one more time.” Straight, to your heart like a cannonball. The spoken section even reaffirms that “There’s a girl for every boy,” which was nice to know in the 11th Grade and nice to know now if you’re in between embraces. Their lives were saved by rock ’n’ roll.

And rescued not even once this side but twice at least: “If You and I Could Be As Two” comes complete with spoken intro: “I kicked my heart when I saw you standin’ there in your dress of blue/The storm was over, my ship sailed through!” How could it not’ve? Perfect penetration, perfect joy. It’s the eternal teenage dream, rendered in a classic ballad form: “What is this feelin’?/What can I do? lf you and I could be relieved/To walk and talk and be deceived/I’d give my all, and more I would do,” even to the point of “Sew this wicked world up at the seams.” Love will win, and despite the Utopian cast which links it to such prime slices of puppylove megalomania as the Troggs’ “Our love Will Still Be There”, Van is realist enough to declare his willingness to be deceived, knowing full well he’s gonna be anyway whether he apprehends any sweetness or not. The most pragmatically horny anthem you could name.

“I Like It Like That” ain’t Chris Kenner’s 1961 hit; today they’d probably call it a boogie, though it’s closer to a shuffle, a traditional medium-tempo R&B form common to many British getdown bands of the period. You can dance to it and you don’t need a Funk & Wagnall’s to apprehend the kozmik import of the words. Same thing applies to the closing raveup, Bobby Troup’s “Route 66”, which was one of the few songs that Chuck Berry ever wrote or popularized that the Rolling Stones managed to cut old Chuckle on, and even though this version don’t cut the Stones’ (that’d be a mighty tall order), its latter-day-barrelhouse piano and cheerfully (beerfully) bashing drums make for more great party music, taking the album out on a joyous note.

In between those two mainstream whoopups, however, lies one of the greatest pieces of pure psychedelic music ever recorded: “One Two Brown Eyes.” Sure, it preceded the fad, doesn’t sound anything like Chocolate Watch Band ersatz fuzz-feedback anyway. What makes it really chilling is that it’s so lucid, deliberate and ungimmicky. Strange as anything Astral Weeks, perhaps stranger, more vein-chilling than “T.B. Sheets,” it’s put together like no other song here or elsewhere, with elements that shouldn’t mix in a month of stolstices but somehow, eerily, do. Like the weird irony of the tinkling percussive background (glockenspiel?), not to mention the infernally, surrealistically vindictive lyrics. Or the brilliant use of the pocketknife alternative to bottleneck guitar, which slithers and slides and makes all appropriate incisions, almost as if peeling skin away from a still-warm body. A further perverse twist is provided by the underpinning of a bossa nova beat. Astrud Gilberto will never sing this, though, that’s for sure. “I’m gonna cut you down to my size,” hisses Van, and you look at the diminutive unsmiling presence on the old album cover and think simultaneously of A Clockwork Orange: real horror show. Well, he does say “Don't read about it in good books,” and it ain’t nothing like Lou Reed singing “Like a dirty French novel” or Joni Mitchell watching “all the pretty people reading Rolling Stone.” Beyond Sade. Bizarro, years ahead of its time in both that and its structure, and totally coherent to boot. The Chill as Van hasn’t rendered it since save perhaps in some of the remoter labyrinths of Astral Weeks. And nobody can put The Chill on like he can, and he don’t even have to indulge in no juju hocus-pocus; plain old fashioned cold blooded virulence does just fine.

This is not the latest or the last Van Morrison album you’re ever going to get, but before scrawling my John Hancock at the end of these perhaps overly effusive notes I must say that when it comes to this man’s music you're never going to hear anything better than the best moments of these two albums. Which is not at all to denigrate his current work, but to note that genius never stands still and when he laid down these sides with Them he was moving at a pace perhaps more furious than he has ever matched since, simply because it was all new and there were so many things to say at once that the man literally exploded. I don’t know much about his personal life, which is probably just as well for our purposes here, since I suspect that the creative eruption comprising these records, Blowin’ Your Mind and Astral Weeks laid the same heavy tax on his soul and body as that which Dylan endured in the process of living and recording the cycle that ended with Blonde On Blonde. Like Dylan, Van seems to have found a modicum of the harmony he was always lunging after in his post-apocalypse, connubial country life. But that does not make the artistic product of the apocalypse any less crucial and exciting – more so, if anything. Even wanting to believe that we don’t really want our heroes to immolate themselves to sate our vicarious craving for the truth and profundity and danger they have lived, we’ll always have the disturbingly beautiful music of the outer edge to move and keep us aware of what lies there. I think Astral Weeks was Morrison’s haunted cathedral erected on that precipice, and much of the music here belongs to an earlier, perhaps easier and certainly more prosaic period. But it’s inescapable that some of the music here, and it is usually the very best of it, comes from that singed outpost on that harrowing highway where artists push against either the looming crunch of the juggernaut or outward into sheer nothingness. And that extremism is this music’s strength. “Mystic Eyes” is strong and vital because for all its agony and desperation its totally unafraid.

And it’s strong because, like everything around it on these two pieces of wax, it’s real rock ’n’ roll of the sort that comes rarely and scores your life without your even trying, by its truth. Music like this can’t stay out of sight long, and if all goes well and there are no contractual snags this company may even get around to putting out a second collection of early Van Morrison-Them material in a few months, with all the goodies and masterpieces that a mere two albums couldn't hold: “Baby Please Don't Go,” “All For Myself,” “Richard Cory,” songs from English albums like “Just a Little Bit,” “I Gave My Love a Diamond,” “You Just Can’t Win,” “Bright Lights Big City,” “The Story of Them,” “My Little Baby,” “Don't Start Crying Now” and all the others.

In the meantime, should you be standing even now in the records section of the local department store with the plastic slit by thumbnail and this package open, reading these words and trying to decide... don’t hesitate.

Get it while you can.

Lester Bangs

CREEM Magazine

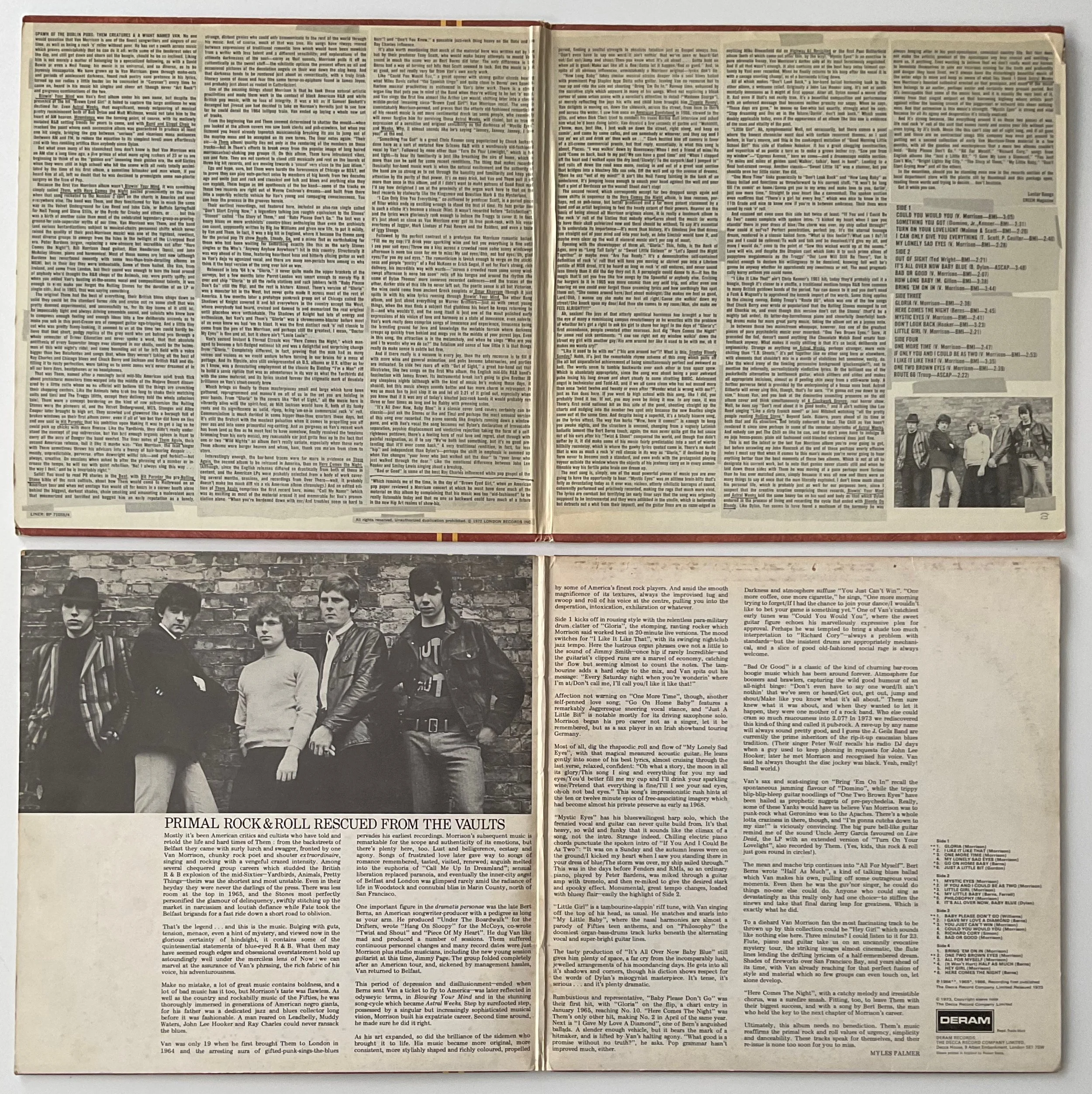

Bangs’ sleeve notes – a design nightmare – overly crammed, squeezing out the very cool photo. The UK edition has a better set of tracks . . . MORE! . . . and a readable layout

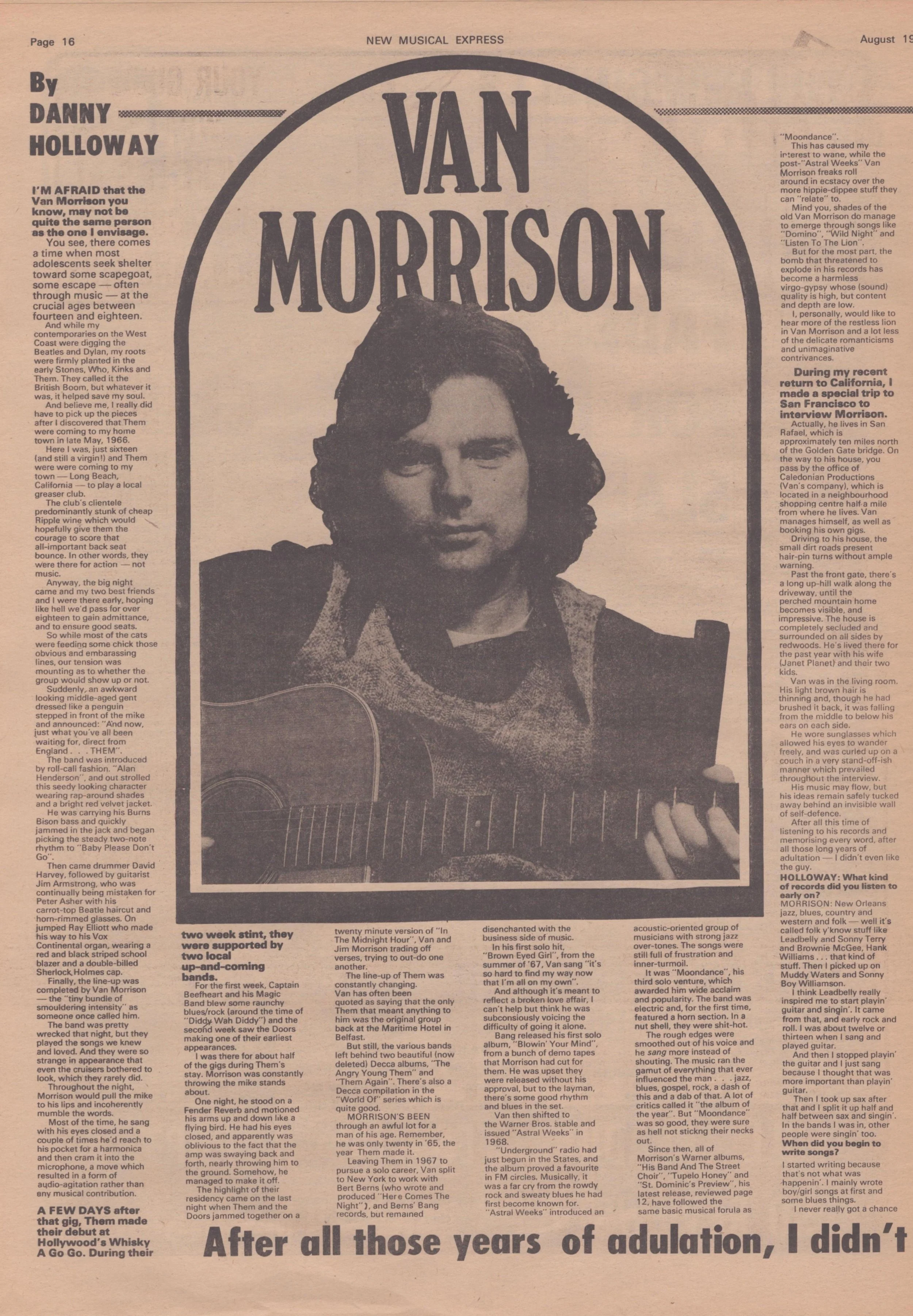

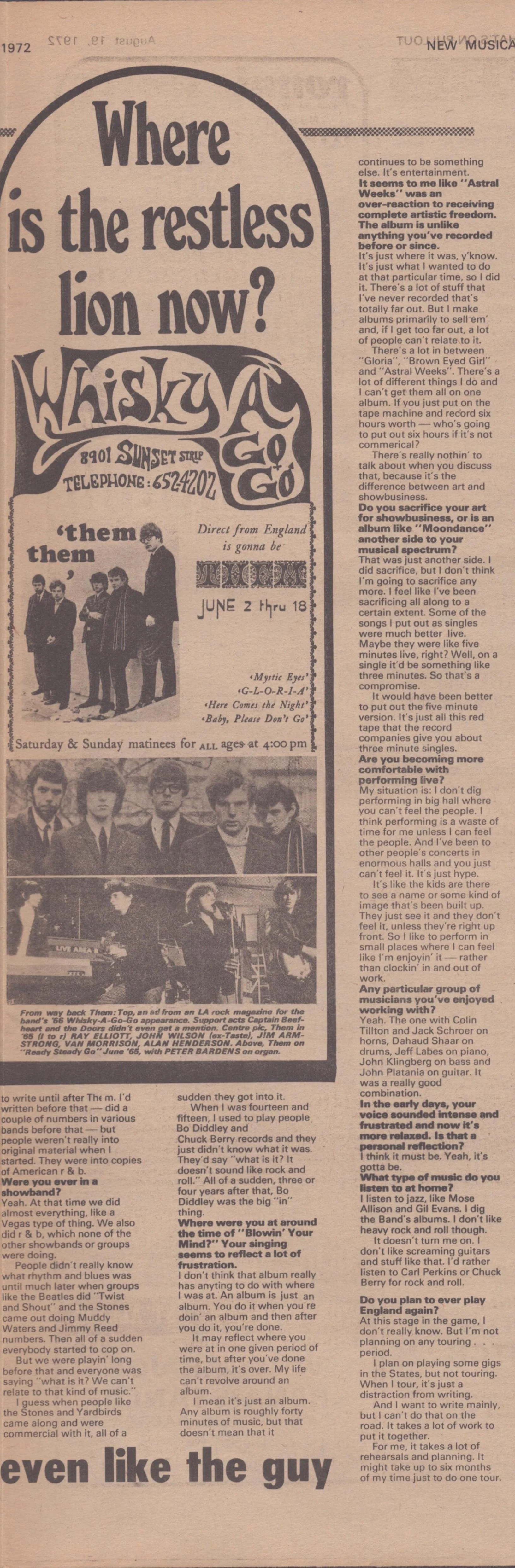

Danny Holloway recalls going to see THEM play at the Whisky A Go Go and elsewhere . . . I wish I’d been with him . . .