First published in August 1970, The Scene is subtitled a ‘documentary novel’ that cuts between the fictitious story of starfucker Lori Thomas and interviews with anonymous real-life players. The book exploits the same prurient material on groupies as Jenny Fabian’s 1969 tale, Rolling Stone’s cover story on electric ladies from the same year and the film Groupies (1970). The title refers to the rock scene, the groupie scene, making the scene and to Steve Paul’s Scene club, New York, where Lori works the angles with touring British groups, sucking and fucking her way to oblivion. Before she makes the ultimate scene Jahn chucks in a deux ex machina and resets her sights not on bedding the next superstar but on becoming one herself.

Before her debut performance, Lori reflects back on seeing The Stooges making their scene at The Pavilion, Flushing Meadow Park a year earlier:

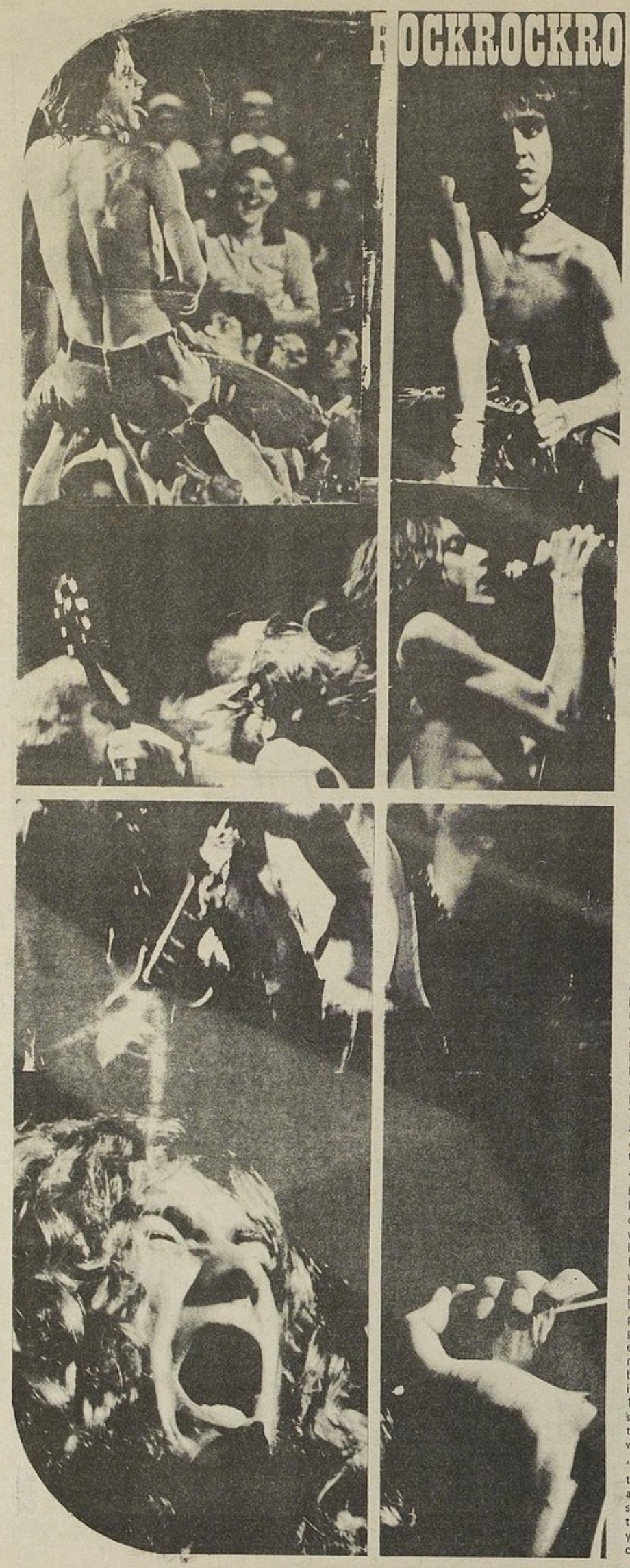

Lori lay in bed thinking. Last summer she spent one weekend out at The Pavilion, which is in the middle of the 1965 World's Fair site in New York. It was beautiful – rock and roll and beautiful – and she had never seen anything like this kid, this kid Iggy, the lead singer for The Stooges, formerly The Psychedelic Stooges. Iggy had acquired a reputation as an oddity. A beautiful, strange oddity from Ann Arbor, Michigan. She had heard of him from a lot of people and saw ads in The Village Voice that showed Iggy lying on stage with the microphone stuck in his mouth like a Tootsie Roll Pop. He was lying on his stomach eating the microphone and behind him the bassist was smiling and pushing the tip of his bass into Iggy's ass. Or at least that's the way it looked. She had flipped, she remembered, really flipped!

The show was their New York debut, one of two sets the Stooges played in support of the MC5. Jahn had covered the gig for the New York Times where he emphasised the band’s performance art credentials: ‘The Stooges probably belong Off Broadway more than to the world of rock ’n’ roll . . . They are best classified as a ‘psychedelic’ group. Their loud droning sound is spiced with the slippery notes of Ron Asheton, a guitarist, and the guttural howlings of a singer, known only as Iggy. . . He goes through simple but tortured gymnastics built around a Midas-like ability to turn everything he touches into a phallic object. He caresses himself, he rolls and squirms’.

In his novel, Jahn’s three column inches are amplified and expanded – Iggy’s embodiment of carnal expression now pushed to the fore:

There were maybe 2500 people sitting on the flat concrete in front of the stage. The floor of the pavilion— the old New York State Pavilion from the fair—is a hundred-foot map of New York State. The stage is set at about Canada. The bathrooms are just south of Long Island. The group was introduced to all these people sitting on the ground on a cool, windy night. The drummer, guitarist, and bassist took the stage and tuned and Iggy walked up a ramp and onto the stage. He was wearing tennis sneakers and dungarees cut down to make shorts. Nothing else. He is about five-foot-eight and very wiry. He walked on the stage and right as he did somebody yelled, ’Iggy sucks off Jim Morrison’. Iggy reacted like a psychedelic spring. ‘Suck my asshole’, he screamed. He walked on stage and the set began. The music was all one—all one big clap of sound that sort of rumbled and droned ominously. No part, save an occasional guitar riff of merit, was separable from any other. All attention was on Iggy, and the group provided his soundtrack.

Per Nilsen and Carlton Sandercock, The Stooges: The Truth Is In The Sound We Make (2022)

He held the microphone and moved. He moved like no other performer she had ever seen. I mean, Lori thought, I have seen unusual performers. Peter Townshend is pretty strange in the way he moves. Jim Morrison is weird in a camp way. Frankie Gadler of NRBQ is strange. But this kid Iggy Stooge, this former high school valedictorian and most-likely-to-succeed was like nothing else. He held the mike with all this droning, cataclysmic noise behind him, and he bent at the waist. He bent over backwards and he nearly touched his head to the floor. He massaged the mike stand. A photographer standing there remarked that Iggy was incredible because everything he touched turned into a cock! He jerked off the mike stand. He was on his back writhing on the stage, he was on his feet leaning to gravitationally impossible angles, holding the mike stand and singing about not having any fun. No fun. He represents the sexual boredom of the seventeen-year-old radical, it seemed. This is his thing; the thing that made him popular with the New York rock and hip literati. He went to the drummer and took a drum stick and scratched his chest and stomach until he began to bleed! No fun! He is turned off by society and so he is totally turned inward, to himself. Autoerotic rock and roll! He can't get it outside so he gets it inside, by turning everything he touches into a cock! Fantastic, Lori thought that night. Iggy scratched his chest and belly with a drum stick and then with his fingernails, and then he was singing right by the edge of the stage. He was singing about fucking you, and doing this to you, and he was pointing at a girl sitting a few feet from the stage, sitting with her gorgeous blonde ass on top of Syracuse! Then, a kid a few feet behind her gives Iggy the finger! This kid with short hair and a college jacket gives Iggy Stooge the finger. Iggy stops singing, crouches. Gets down on all fours. Then he springs, he springs into the audience, and lands on all fours a little bit in front of the kid, who now is wondering why he is here. Iggy is on all fours, and he has this very bad expression on his face, and from the stage behind him this music is pounding and crushing across Flushing Meadow Park. Iggy is on all fours, with this very bad expression. He is staring at the kid who gave him the finger, and slowly he begins to walk, on all fours toward the kid. The kid begins to sweat and look around for friends. There is a noise. The audience stands up, and Lori cannot see. There is shouting and much pushing and all 2,500 people are standing, straining to see. Iggy is in the middle of the crowd for another minute or so. Then you see him crawl back on stage, out of the crowd. The crowd is aflame, for reasons they do not know. Iggy is challenging everything they have come to accept about concert relationships, and about male sexuality. He is so goddamn sensual. The males with the short hair and the Corvettes feel it and they don't know what to do with the feeling. Some of them are throwing containers of orange drink at him. Iggy is back on stage. Still on his hands and knees he crawls across stage and grabs the guitarist. Instantly, the Midas touch; the guitarist turns into a phallic totem. Iggy drags him down, still playing; the guitarist is still playing. Iggy hugs his legs for a time, then lets him go and crawls off.

Iggy crawls off behind the bank of amplifiers that rim the back of the stage. He is behind there for a few minutes, the music crashing, and then the spotlight picks him up crawling out from behind the amps on the other side. Rock and roll! What is going on? Iggy can be seen at the far right corner of the stage. He gets into a racing start position. He stands like a sprinter ready for the race. Then he sprints wildly across stage at full speed and does a perfect racing dive into the audience, which is still standing! Head first, hands first! He makes it all the way to Albany, feet together, hands together in front of him, and crashes onto the milling heads, taking out about twenty-five people! There is more screaming and pushing. Everyone is trying to see, jumping to see. You can't see. Lori couldn't see. A minute goes by and Iggy crawls back out of the audience and onto the stage. He stands and finishes the song and the group walks off. They have been onstage only about fifteen minutes.

A month or so after the book’s publication in October 1970, using the release of the Stooges’ second album Fun House as an excuse, Jahn returned once more to the Flushing Meadow Park performance; this time in his widely syndicated column ‘Sounds of the 70s’:

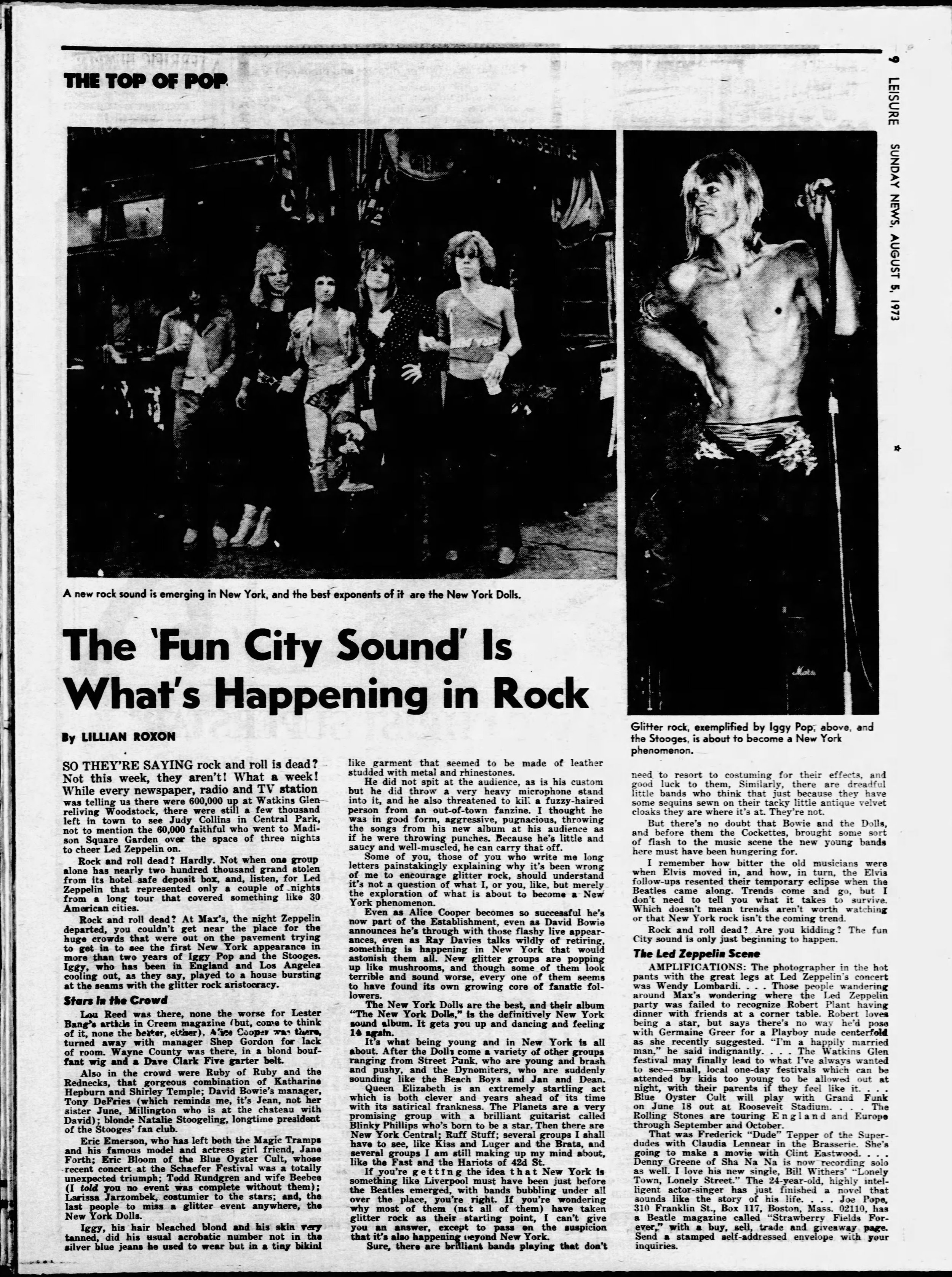

Peter Townshend of The Who used to destroy guitars at the end of a set. On those occasions, the audience would be drawn, transfixed, to the scene of the destruction like the traditional moth to a flame. With Iggy it is the same thing. He writhes. He moans. He seems totally self-involved. He rubs his body, he con-torts, bending over backwards until his head nearly touches the floor. He rolls his tongue around. He makes grotesque shapes with his lips. He is very ugly and precociously sexual. The audiences love it. They don't understand it. Neither does he, most likely. But they are drawn to watch him with mouths agape.

Watch the freak! It’s great fun.

Consider this episode from the Stooges' concert of last year at the Pavilion in New York. The Pavilion is the former New York State Pavilion at the 1964-65 World's Fair. The ground is a giant map of New York State. For this occasion, the stage was set up along the Canadian border. The other end, the men's rooms, were just south of Long Island. The audience was seated on the floor, on top of New York State.

Iggy did his normal writhing, then spotted a blonde sitting on Syracuse. He stared at her a long moment until a kid behind her made an obscene gesture in his direction. Iggy sprang into the audience. He landed on all fours and began crawling toward the kid, slowly. Just as he reached him, the audience stood up. Much pushing and screaming for a few min-utes, then Iggy crawled back out of the audience. He crawled to the guitarist, pulled him down on the floor, mauled him for a few minutes, then let him go. Then Iggy disappeared behind a bank of amplifiers, emerging on the other side a few minutes later. He got to a racing start position, sprinted across stage, and made a perfect head-first racing dive into the audience, knocking down about 25 people in the vicinity of Albany.

Earlier in the show, he took a drumstick and raked it across his chest until he started to bleed. After another concert he was heard to lament the fact that he hadn't bled enough. While the previous routine was going on, the band never let up for a second on its wall-of-music. A full-color, four-part-harmony version of this episode is included in my just -published novel, The Scene.

Everybody has something to sell.

Six months later Jahn once more brought up the subject of Iggy this time because artist Richard Bernstein also had something to sell: nude portraits of the Beatles, Jim Morrison, Candy Darling and Iggy; the latter one of ‘the new toys of New York pop society’. Jahn thought the Iggy picture was a ‘masterpiece. It’s an actual photo, of the real Iggy, shot by fashion photographer Bill King and turned into prints by Bernstein. “I’ve been selling it from my studio to a lot of people in the music scene”, he says. “Everybody has one”. This edition is only 100 copies. The print shows Iggy leaning slightly to one side, absent-mindedly scratching one arm’.

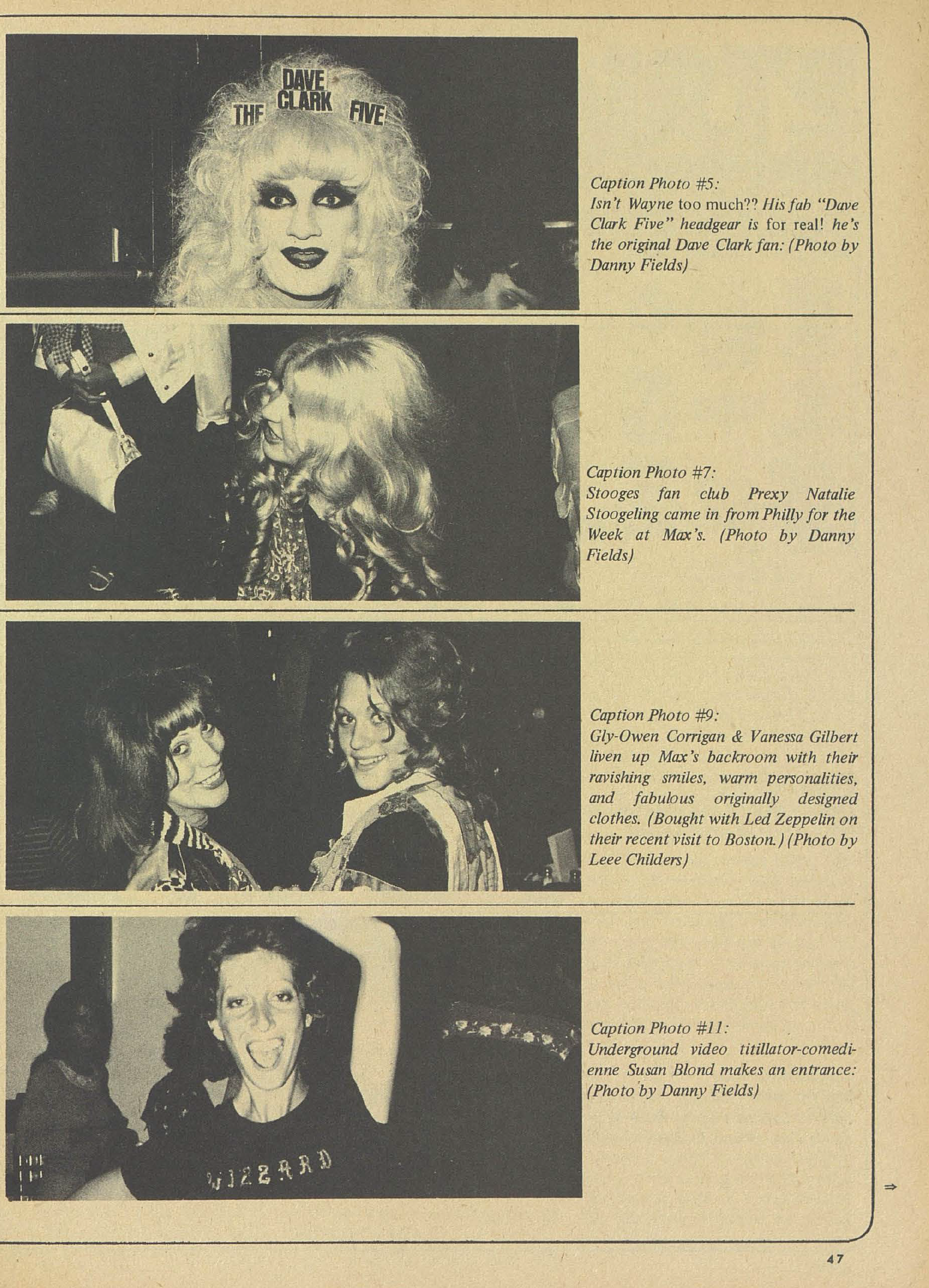

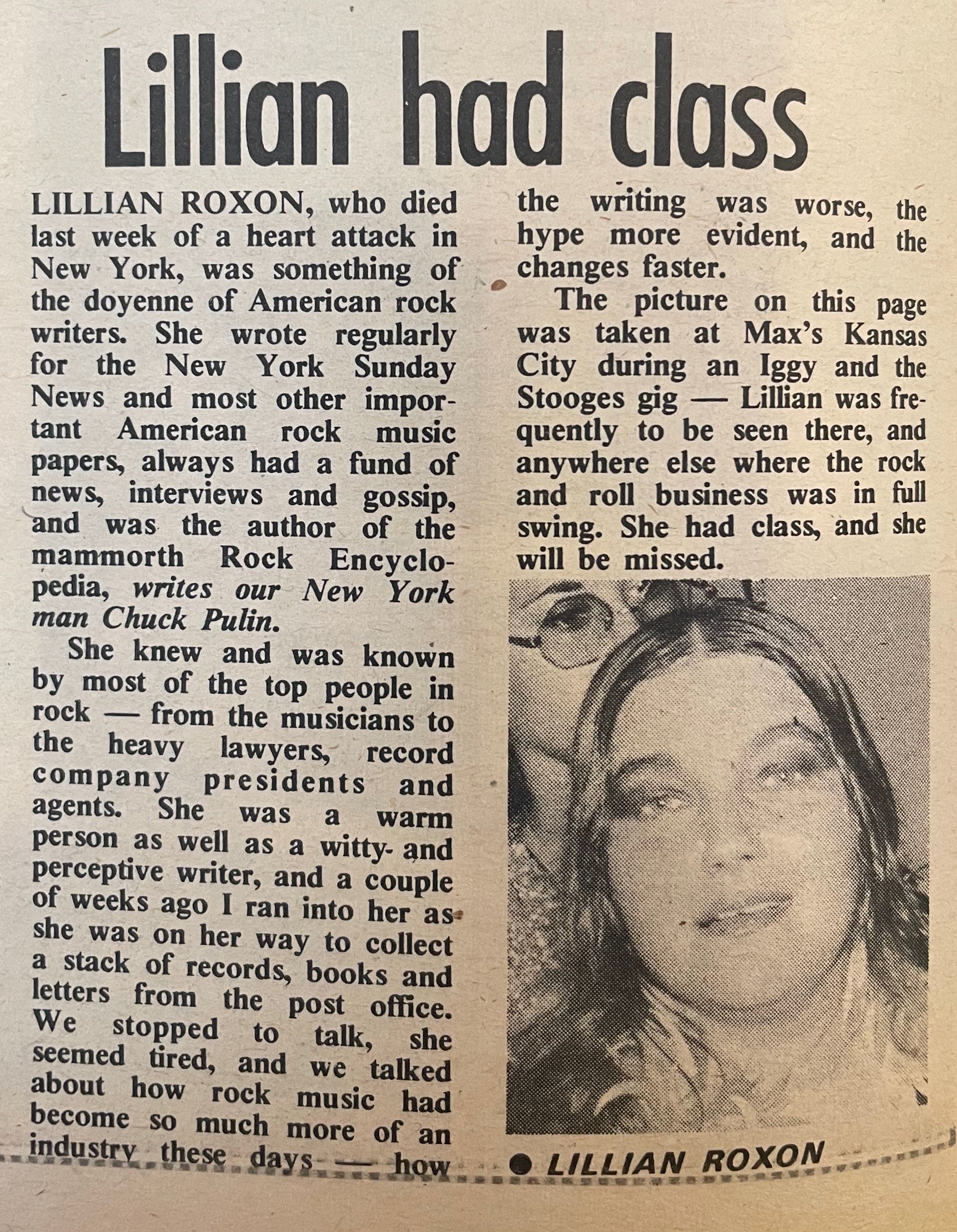

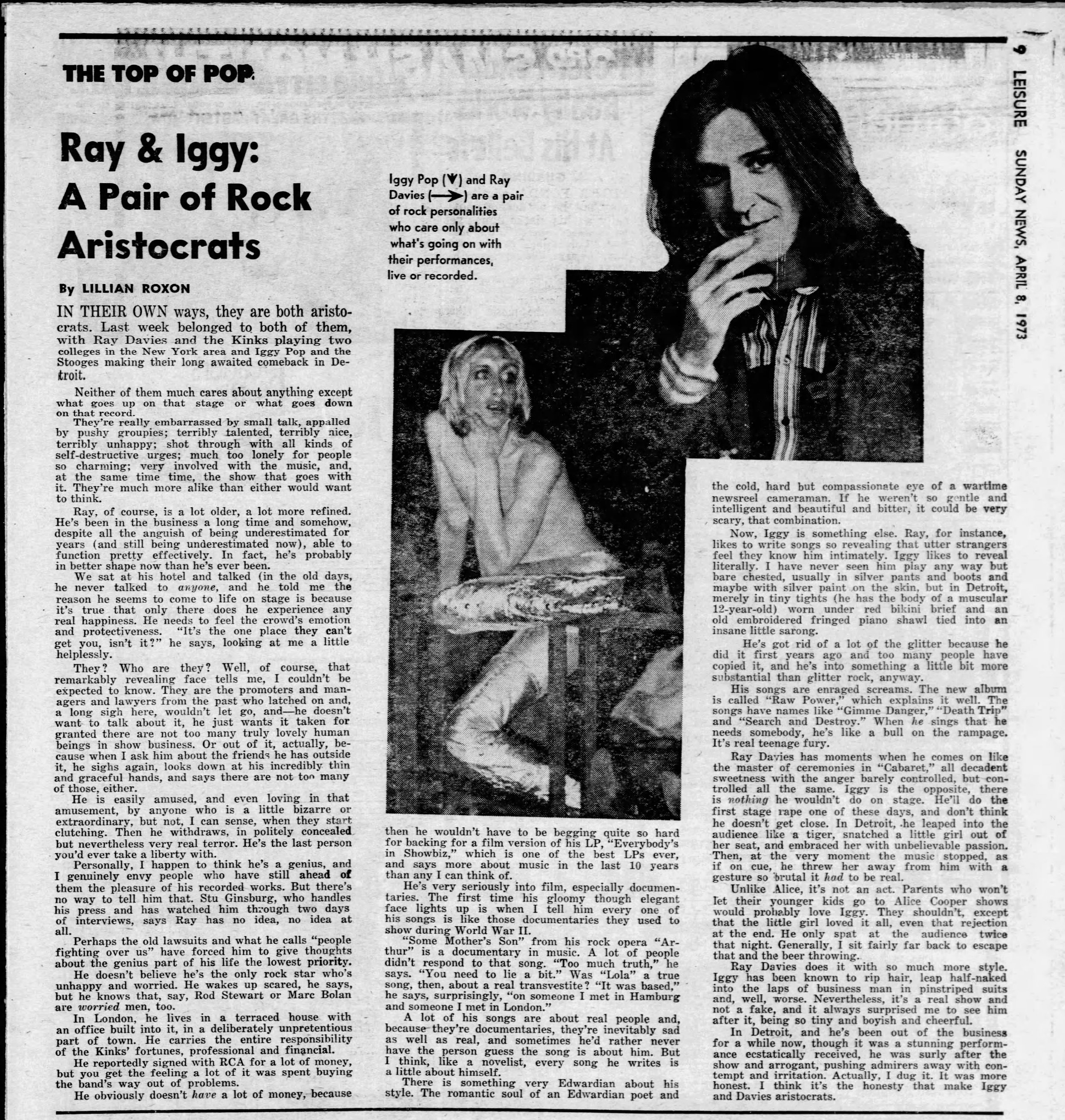

One proud owner of a print, Lillian Roxon, had it prominently displayed in her apartment [HERE] – giving her no small pleasure

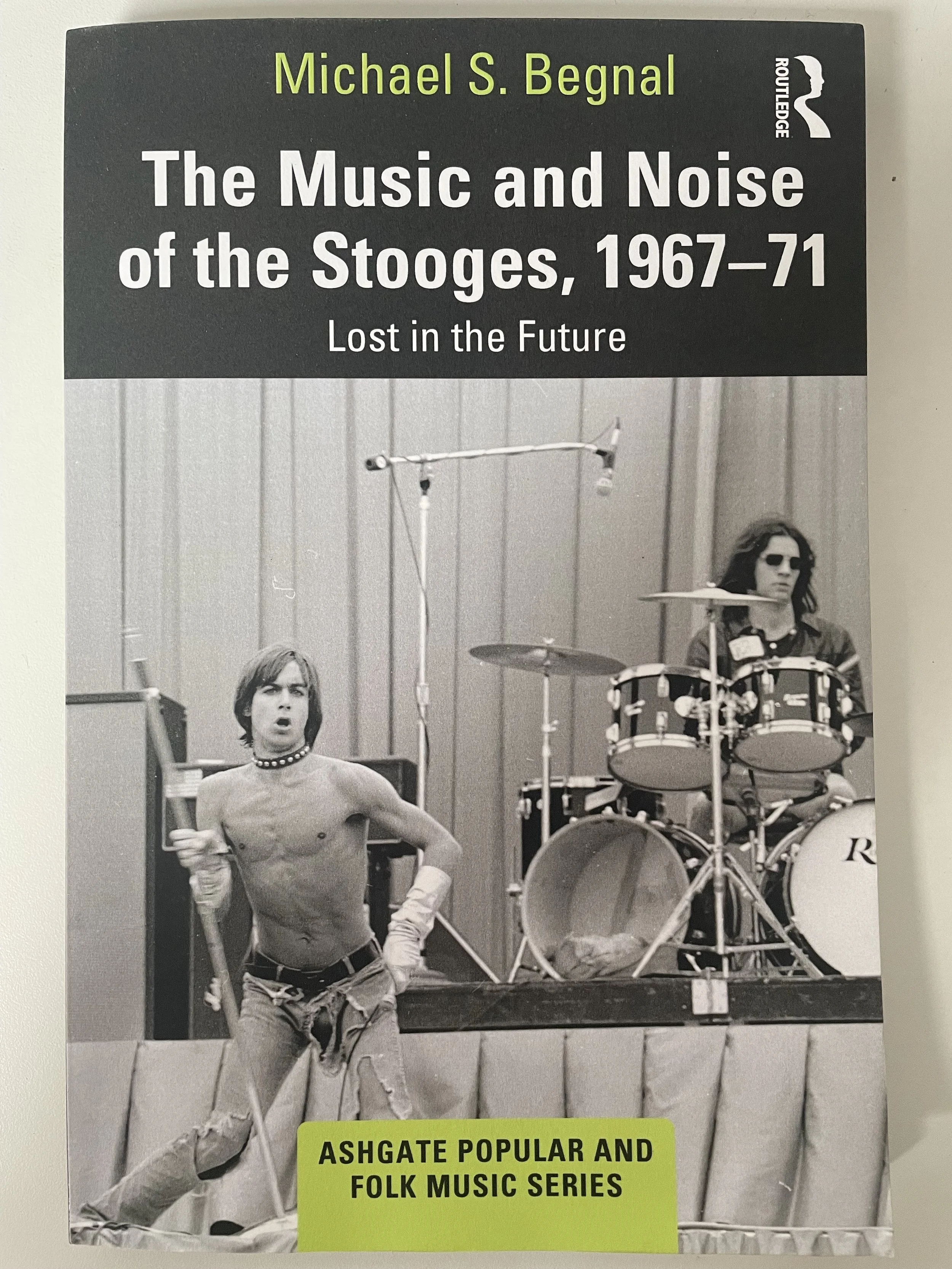

For more on the Stooges’ Flushing Meadow Park sets see Michael S. Begnal, The Music and Noise of the Stooges, 1967–71: Lost in the Future (2022)