A recent acquisition of the two volumes of the Best of the Troggs, released in 1967 & 1968, had me heading back to Lester Bangs’ essay from 1971, ‘James Taylor Marked for Death (What we need is a lot less Jesus and a whole lot more Troggs!)’ ,to see which of the 23 tracks on these comps he had also singled out for praise.

(There are a dozen tracks apiece on the two albums but for an unknown reason the less than essential b-side of ‘Wild Thing’, ‘From Home’, gets a place on both discs).

Turns out Bangs only put seven tracks under analysis on his groin thunder odometer: ‘Wild Thing’, most obviously, ‘I Want You’, ‘I Can’t Control Myself’, ‘Give It to Me’, ‘I Can Only Give You Everything’, ‘Gonna Make You’, ‘66–5–4–3–2–1’ and ‘I Just Sing’ (which didn’t appear on either of the Best of volumes). Honourable mentions along the way are given to ‘Anyway That You Want Me’, ‘With A Girl Like You’, ‘Girl in Black’ ‘I Want You to Come into My Life’ and ‘Night of the Long Grass’.Bangs kicked off his essay with his preferred trope of directly addressing his reader in what might turn out to be a conversation, debate, argument or rhetorical ramble. I’m not sure he knows which it will be until the piece is done. Here’s the rumpus:

PART ONE: KAVE KIDS

All right, punk, this is it. Choose ya out. We're gonna settle this right here.

You can talk about yer MC5 and yer Stooges and even yer Grand Funk and Led Zep, yep, alla them badasses’ve carved out a hunka turf in this town, but I tell you there was once a gang that was so bitchin' bad that they woulda cut them dudes down to snotnose crybabies and in less than three minutes too. I mean their shortest rumble was probably the one clocked in at 1:54 and that's pretty fuckin swift, kid. Oh, they didn't look so bad, in fact their appearance was a real stealthy move ’cuz they mostly photographed like a bunch of motherson polite mod clerks on their lunch hour, but they not only kicked ass with unparalleled style when the time came, they even had the class to pick one of the most righteous handles of all time: the Troggs.

Perfectly named, the Troggs sprung fully-loaded out of the primal ordure that all great rock n’ roll comes from. Subterranean Neanderthals who briefly stepped into the light to promote a clutch of hit singles:

’Cause this was a no-jive, take-care-of-business band (few of the spawn in its wake have been so starkly pure) churning out rock 'n' roll that thundered right back to the very first grungy chords and straight ahead to the fuzztone subways of the future. And because it was so true to its evolutionary antecedents, it was usually about sex, and not just Sally-go-to-movieshow-and-hold-my-hand stuff, although there was scads more of that in them than anyone would have suspected at first, but the most challengingly blatant flat-out proposition and prurient fantasy.

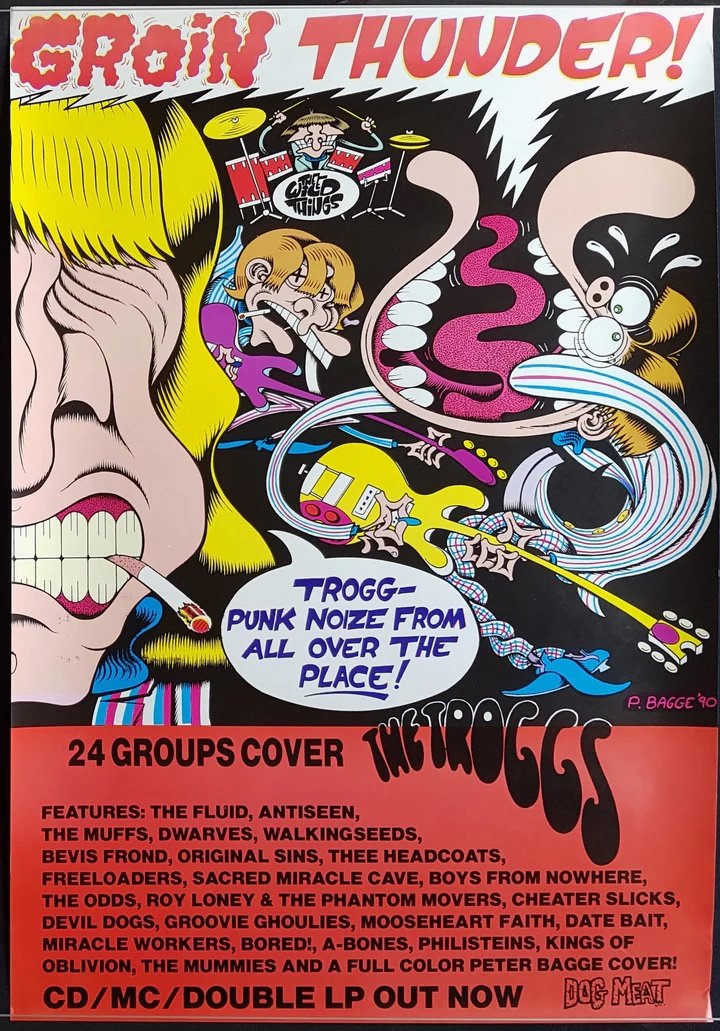

That’s the cue for Bangs to range far and wide over his adolescent wet dreamscapes. His term for the Troggs’ libidinous thrusts was ‘groin thunder’ which was an image as impeccably realised as the band’s name. Its most basic expression, he wrote, is obtained in ‘I Want You’:

This is the Troggs at their most bone-minimal (which is also where they are usually most effective). Like the early Kinks, they had strong roots in ‘Louie, Louie’, which is where both song and guitar solo issue from here. The lyrics are almost worthy of the cave: ‘I want you / I need you / And I hope that you need me too . . .’ The vocal has a musk of yellow-eyed depravity about it, and the singer sounds absolutely certain of conquest-steady, methodical, deliberate. This is the classic mold for a Troggs stalking song.

Bangs developed his line:

‘Gonna Make You’ is more of the same, Diddley rumbleseat throbbing with sexual aggression and tough-guy disdain for too many words, while the flip side of that single, ‘I Can't Control Myself’, begins to elaborate a bit. It opens with a great Iggyish ‘Ohh, NO!’, employs a buckling foundation of boulderlike drums as usual, and takes the Trogg-punk's intents and declarations onto a more revealing level. ‘Yer socks are low and yer hips are showin’,’ smacks Presley in a line that belongs in the Great Poetry of Rock 'n' Roll Hall of Fame.

I hear ‘slacks’ not ‘socks’ though maybe the latter fits better with whatever fetish or ‘pube punk fantasy’ Bangs had a predilection for. ‘A two-sided single whose titles were “Give It to Me” and “I Can't Control Myself” was on a collision course with some ultimate puissant bluenose from the start, and sure enough it was banned in America’.

About midway through his essay Bangs hits the caps lock on his typewriter and finally lets loose about why all of this fuss n’ bother over Reg and the Boys is worth his reader’s attention:

THE LESSON OF ‘WILD THING’ WAS LOST ON ALL YOU STUPID FUCKERS sometime between the rise of Cream and the fall of the Stooges, and rock 'n' roll may turn into a chamber art yet or at the very least a system of Environments.

Bangs was not wrong, the Velvets, MC5 and the Stooges, he wrote, all gainfully pushed back against the tide of musical civility but they could not be the primal thing itself, they were all too knowing, too self-reflective, too intellectual. As for the Troggs:

Quite possibly they understood or ruminated about what they were doing on very limited levels. Because that was all that was necessary. Had they been a clot of intellectual sharpies hanging out in the London avant-garde scene, they would most likely have been a preening mess unless they happened to be the Velvet Underground who were a special case anyway. I really believe maybe you've gotta be out of it to create truly great rock 'n' roll, either that or have such supranormal, laser-nerved control over what you are consciously manipulating that it doesn't matter (the Rolling Stones) or be a disciplined artist with an abiding joy in teenage ruck jump music and an exceptionally balanced outlook (Lou Reed, Velvets), or chances right now are that you are almost certain to come out something far less or perhaps artistically more (but still less) than rock 'n' roll, or go under.

From here on in James Taylor and his self-obsessed singer/songwriter peers become the target of Bangs’ ire. But Bangs is soon back on the trail of Reg Presley and co., chasing down the real meaning of ‘66–5–4–3–2–1’ – the countdown to penetration; the S&M overtones of ‘Girl in Black’ and the anal sex pleasures espoused in ‘I Want You to Come into My Life’ and, of course, the drug scene of ‘Night of the Long Grass’. He spends a good deal of time on ‘I Just Sing’ – ‘an anthem of loneliness and defiant individuality’ that he likens to the Stooges ‘No Fun’ but by this point in his essay the band’s catalogue is looking empty and Bangs is running on fumes.

I’m not a hardcore Troggs fan, other than the two Best of LPs, I’ve a handful of singles and the 3xCD set Archeology from 1992 that Bill Inglot, Bill Levenson, Andrew Sandoval and Ken Barnes put together, the first disc is mostly essential 1966–67 cuts, disc two is filled with not so essential selections from 1967–76. Disc three is the infamous Trogg Tapes . . . Part of the brilliance of Bangs’ take on their catalogue is to ignore the copious amount of filler they recorded, which were anything but explosions of groin thunder. Bangs name checks only twelve cuts (his editor Greg Shaw questioned this self-imposed limit – see above), each Best of has a dozen, and I think that is the perfect number for any Troggs set, so here’s my 2 x 6:

‘Gonna Make You’/’ ‘66–5–4–3–2–1’/‘I Want You’/‘I Can’t Control Myself’/‘Anyway That You Want Me’/‘Girl in Black’//‘Night of the Long Grass’/‘Mona’/‘I Can Only Give You Everything’/‘Anyway That You Want Me’/ ‘I Want You to Come into My Life’/‘Give It to Me’/‘Louie Louie’.

I’ve dropped ‘Wild Thing’ because I don’t need to hear it again and I anyway prefer those rewrites like ‘I Want You’, not because they refine ‘Wild Thing’ but because they amplify what’s great about it. Bangs’ choice of ‘With A Girl Like You’ and ‘I Just Sing’ fall short of my other selections because there’s too much Donovan and not enough Bo Diddley in them for my primitive taste buds even if, on the latter, the band put in a little bit of Yardbird-style faux-sitar licks.

Side one starts off in a hurry with the first three tracks but cools it down toward the end with ‘Anyway That You Want Me’ and ‘Girl in Black’. The last of those two songs comes in at just under 2 minutes and is a solid rip-off of The Who (and all the better for that), while the cello and violin accompaniment on the former, at least in my imagination, following Bangs’ lead, leaks into John Cale’s contributions to the more melodic songs of the Velvet Underground and in Nico’s solo work. Side two stays in mood with ‘Night of the Long Grass’ followed by two non-single tracks, both something of beat standards. Bo’s ‘Mona’ is perhaps the longest cut from 66/7 that they recorded, it has an extended, by their standards, instrumental section but, unlike the Yardbirds say, they are not minded to do much with it; very Stooge-like in its focus, I think. Rob Tyner has said the MC5 recorded a cover of ‘I Can Only Give You Everything’ when the Shadows of Knight got the jump on them and released ‘Gloria’ so they turned to the next best thing in Them’s songbook. I don’t doubt the truth of that but Fred ‘Sonic’ Smith’s slashing guitar riff on the Five’s single is a straight lift from the Troggs’ version.

The last track on my imaginary compilation, which I’ll call I Want –You Want as it seems to adequately distil down the subject and theme of Reg’s songwriting (or maybe I should name it more simply Come), is ‘Louie Louie’ which is at the very heart of the matter. This album cut is by far the best of the period’s covers by a British band and leaves the Kinks’ tepid version far behind even if it doesn’t quite make the grade of the Sonics, whatever it’s a good place to end things.

In his inestimable study of ‘Louie Louie’, Dave Marsh ignores the Troggs version but he homes in on its most potent progeny, ‘Wild Thing’. Marsh writes,

Art it may not possess, but in its own way ‘Wild Thing’ is a rock ’n’ roll classic. The way it descends to lower depths with each bar is so astonishing, its unending thud so remorseless (the Troggs aren't playing this way because it's effective, even though it is – they're doing it because they can't think of anything else), that it just about takes your breath away, clouds your vision, brings unbidden moistness to the corners of your eyes. Of course, these symptoms might be nothing more than a neurological reaction to the axe murder of Western musical civilization, but let's cut the clowns some kind of break.

Bangs would have agreed that the Troggs held no pretension to creating art but they were not clowns, idiot savants perhaps? I like to think of them as carnivalesque jesters capable of upending the courts of Procol Harum, Jethro Tull and the like – a band whose role was to cock-a-snook at those who thought themselves to be the band’s betters.

In January 1965 reader Alex Donald wrote a letter to Record Mirror about Richard Berry’s ur-text, or what he called a ‘pop yardstick’, ‘Louie Louie’:

British pop must be in a desperate state when the whole scene has revolved round one song – The Kingsmen’s ‘Louie Louie – for months. Besides completely copying the Kingsmen’s vocal and instrumental style, The Kinks rose to fame with two watery twists of this classic, then provided us all with endless amusement by recording it openly [released November 1964 on Kinksize Session EP]. Heinz had his second biggest hit ever with another disguised version of this R&B opus [‘Questions I Can’t Answer’] and recently it has been put out as a single on Philips by someone sounding like an in competent one-man band [Liverpool’s Rhythm And Blues Inc]. The parasites should at least leave off the newer American greats.

The Troggs version was yet to come, but I doubt Alex would have felt more kindly disposed toward it than he did to any other of the British covers. One of the issues conveniently ignored in Bangs’ piece was that, at least to the more hip British ears, the Troggs were always sort of behind the times, their parsing of ‘Louie Louie’ or Bo Diddley’s big beat had long been abandoned by the Kinks and Pretty Things. The Troggs in their company feel like an anachronism, or an echo.

Chris Britton’s slash and chime guitar patterns were very obviously modelled on Pete Townshend (checkout the perfected Who-like guitar chord that introduces the bridge in ‘I Can’t Control Myself’) giving a modern steel-sprung edge to the antediluvian thump of Ronnie Bond and Pete Staples’ rhythm section. Just as complementary to Britton’s guitar shards was Reg’s lewd thug sneer, which was often backed by a simple, most un-Who like, vocal refrain ‘da dah, da dah’ that would be varied, when the need for novelty called, from song to song by using ‘pah’, ‘bah’ or ‘lah’. The Troggs didn’t deal in subtlety, that was their appeal. They weren’t complex like the Who, full of contradictions, rather their method was, as Richard Meltzer called it, ‘blatant overstatement’ that Bangs more pertinently named ‘groin thunder’.

Postscript

In June 1973, Melody Maker’s Roy Hollingworth interviewed Reg Presley in Hyde Park. At age 31, the singer was a veteran of the music scene, chubby and ruddy cheeked, he spends much of his time with Hollingworth making lewd comments about women who pass by. Once he was a pop star now he is simply ‘legendary’: the Troggs, were a ‘very heavy little band to be sure. “Punk music”, says Reg. “I like that word punk”’.

The band are capitalising on their fabled status and taking their act onto the university circuit:

‘Was at Hull the other week’, said Reg . . . ‘and after a couple of numbers we thought we’d turned up at the wrong gig. I mean people were screamin’ out and clappin’ and goin’ wild . . . I thought Reg old boy, what’s goin’ on here?’

In the State’s the Troggs’ reputation had been enhanced by the use of ‘Wild Thing’ on a Miller’s beer commercial and then the single is ‘installed on the infamous Nobody’s jukebox, Bleeker Street’ and then word of mouth has done its turn and, ‘so’, writes Hollingworth, here [in New York] starts the Troggs Preservation Society’. Lester Bangs’ piece is not mentioned but Reg’s repeated and enthusiastic use of ‘punk’ to describe his band could hardly have come from a more local source; ‘Wild Thing’ and I Can’t Control Myself’ are ‘very punky records. Hollingworth explains:

. . . everything works in cycles. There’s a progression from a basic quality, through success to an art form – but then it must go back. It doesn’t of course go back to the exact basis it started from. It goes back having collected valid points during its progress. But if it didn’t go back ‘then rock will become as boring as jazz’, as Reg would have it.

‘If you could do anything this year’, Hollingworth summarises, ‘it would be to see The Troggs punking it out for the whole world and making it. It's people like Reg Presley that keep this business sane to a degree . . . ‘We're whap, whap, whap’, said Reg, ‘And I think that’s what it’s about’.

A few months before Hollingworth, NME were rolling with the Troggs as the Punk ur-text . . . December 16 1972