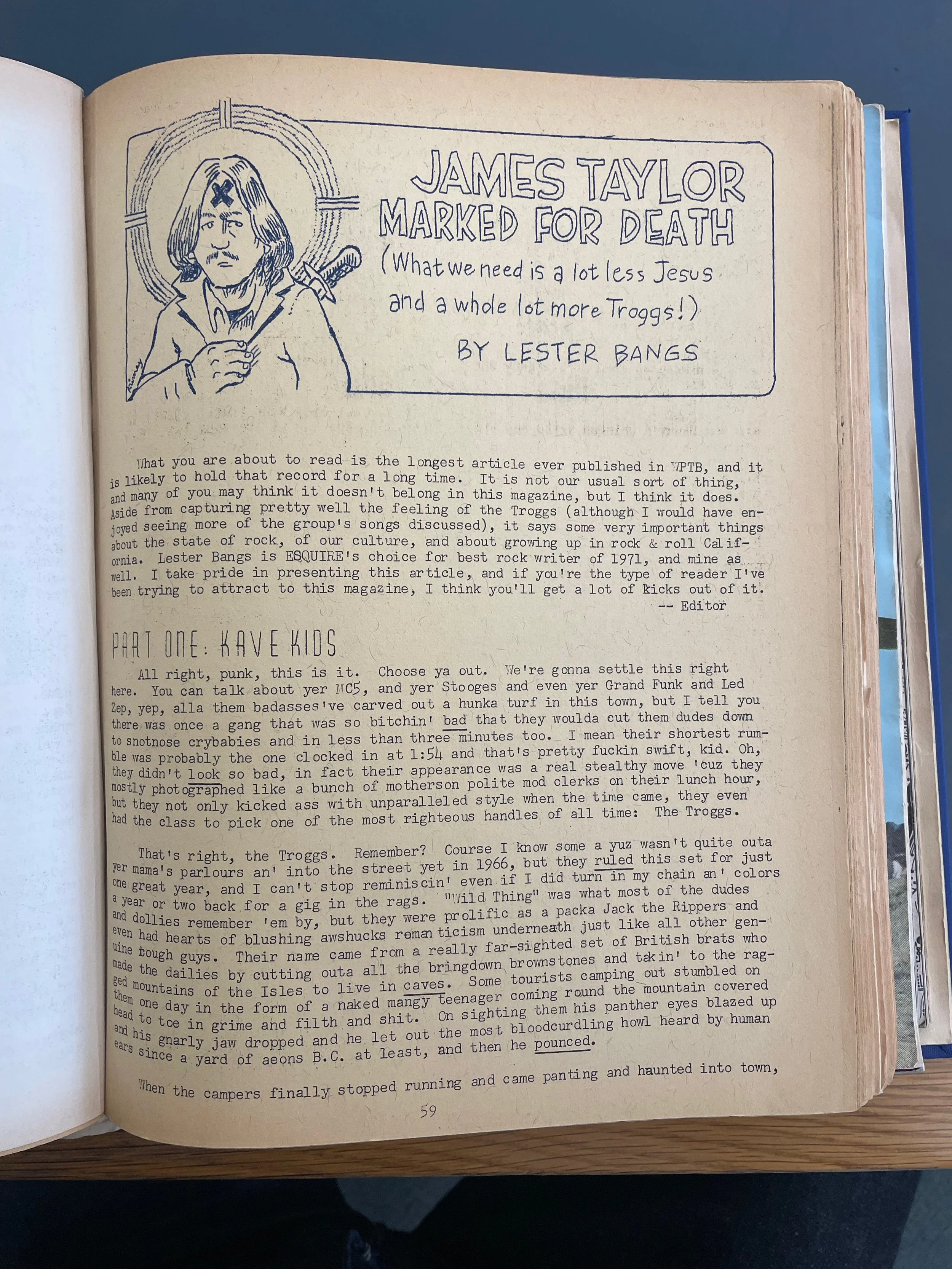

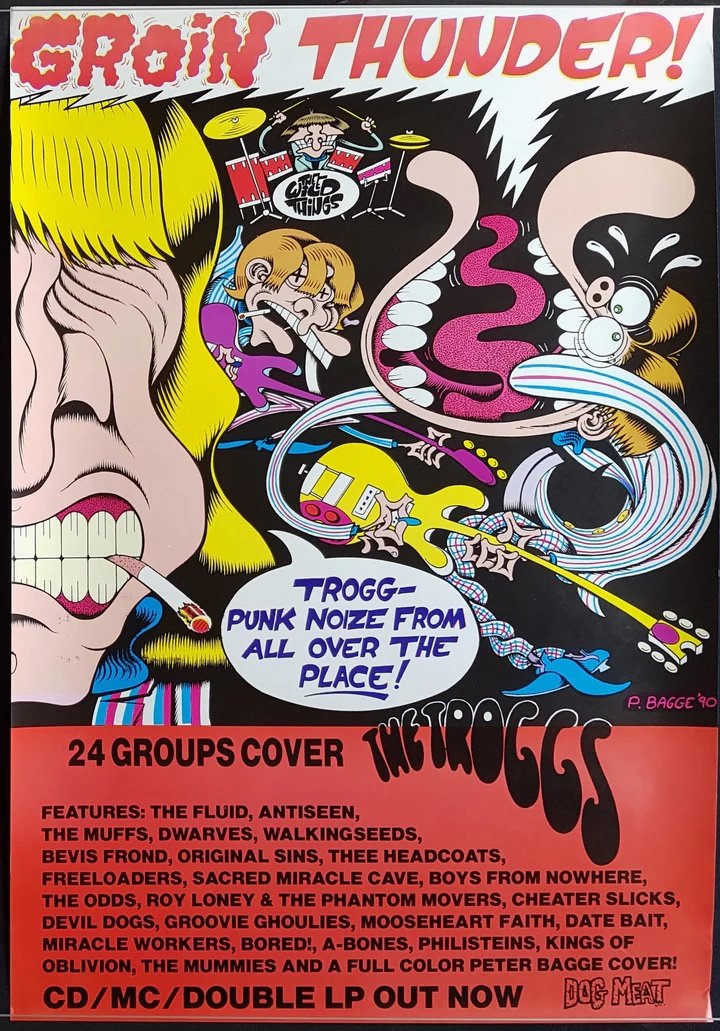

I’m not a hardcore Troggs fan, other than the two Best of LPs, I’ve a handful of singles and the 3xCD set Archeology from 1992 that Bill Inglot, Bill Levenson, Andrew Sandoval and Ken Barnes put together, the first disc is mostly essential 1966–67 cuts, disc two is filled with not so essential selections from 1967–76. Disc three is the infamous Trogg Tapes . . . Part of the brilliance of Bangs’ take on their catalogue is to ignore the copious amount of filler they recorded, which were anything but explosions of groin thunder. Bangs name checks only twelve cuts (his editor Greg Shaw questioned this self-imposed limit – see above), each Best of has a dozen, and I think that is the perfect number for any Troggs set, so here’s my 2 x 6:

‘Gonna Make You’/’ ‘66–5–4–3–2–1’/‘I Want You’/‘I Can’t Control Myself’/‘Anyway That You Want Me’/‘Girl in Black’//‘Night of the Long Grass’/‘Mona’/‘I Can Only Give You Everything’/‘Anyway That You Want Me’/ ‘I Want You to Come into My Life’/‘Give It to Me’/‘Louie Louie’.

I’ve dropped ‘Wild Thing’ because I don’t need to hear it again and I anyway prefer those rewrites like ‘I Want You’, not because they refine ‘Wild Thing’ but because they amplify what’s great about it. Bangs’ choice of ‘With A Girl Like You’ and ‘I Just Sing’ fall short of my other selections because there’s too much Donovan and not enough Bo Diddley in them for my primitive taste buds even if, on the latter, the band put in a little bit of Yardbird-style faux-sitar licks.

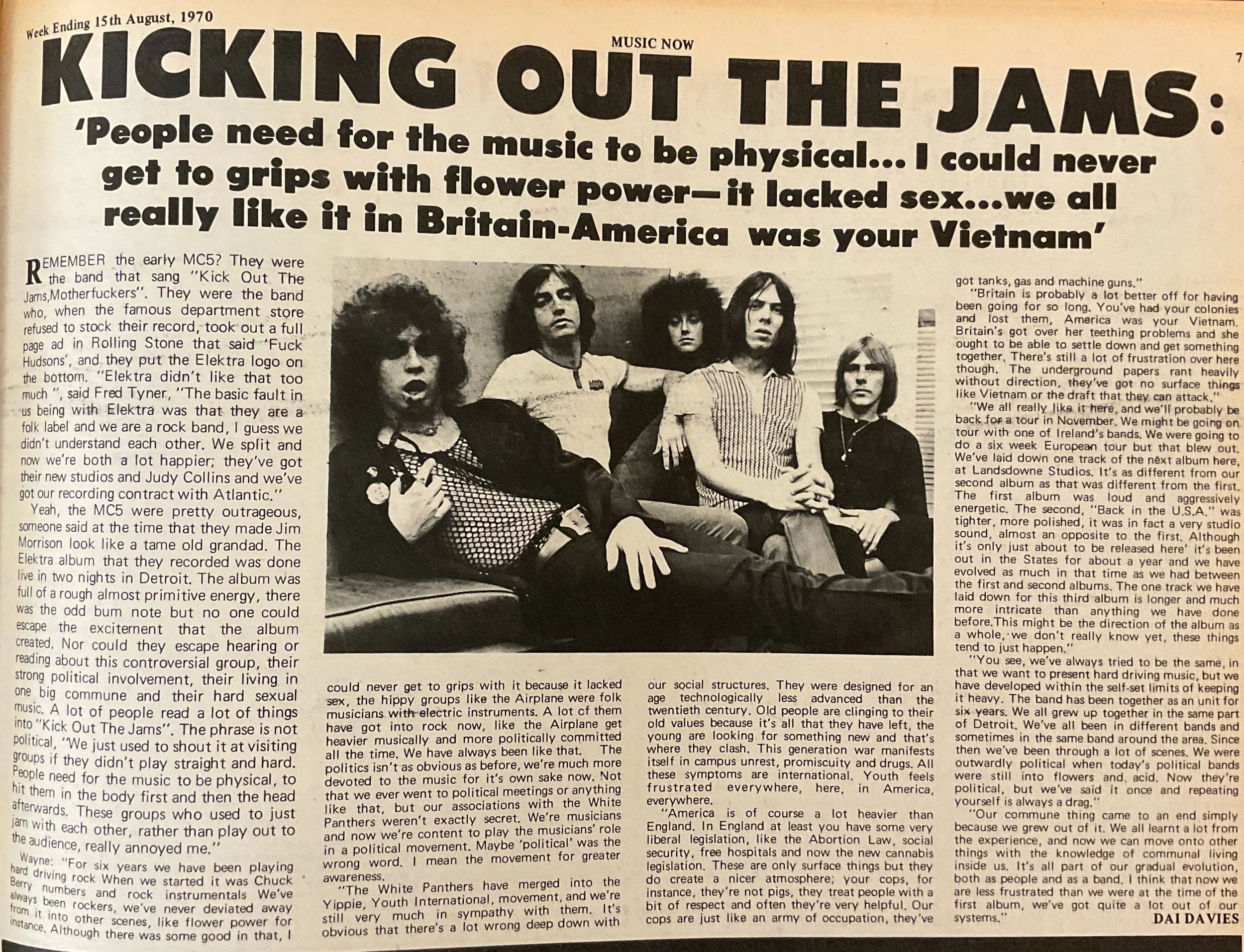

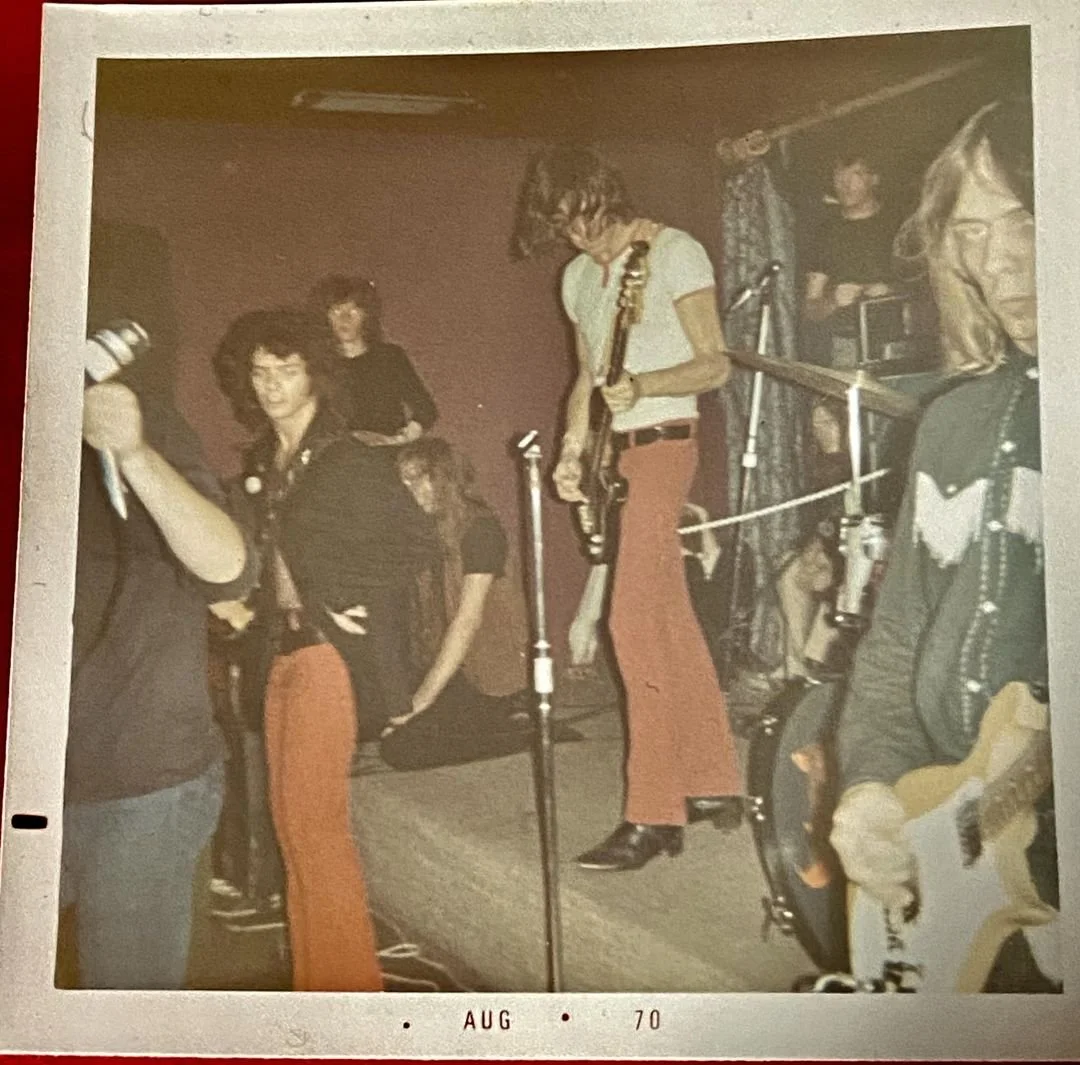

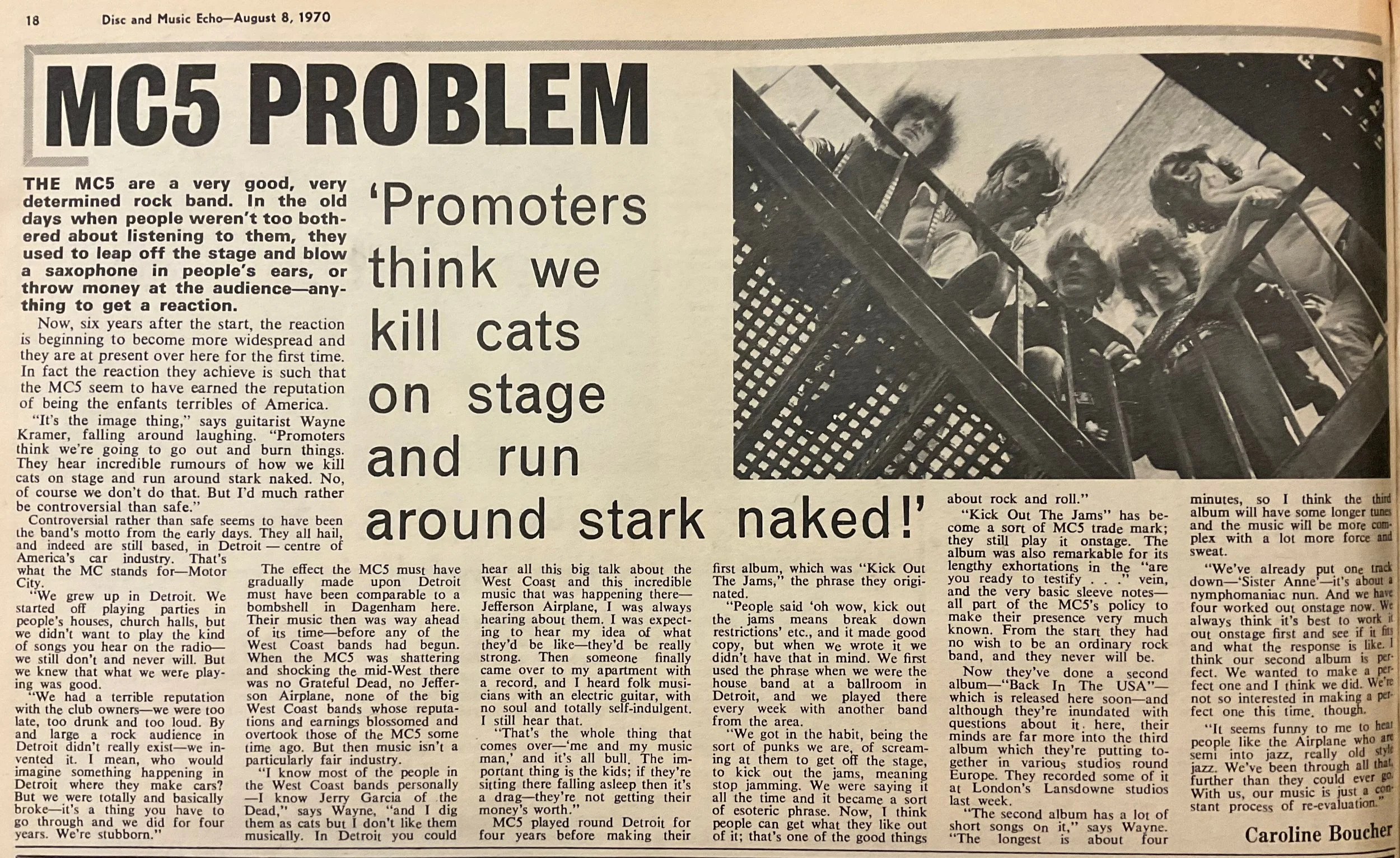

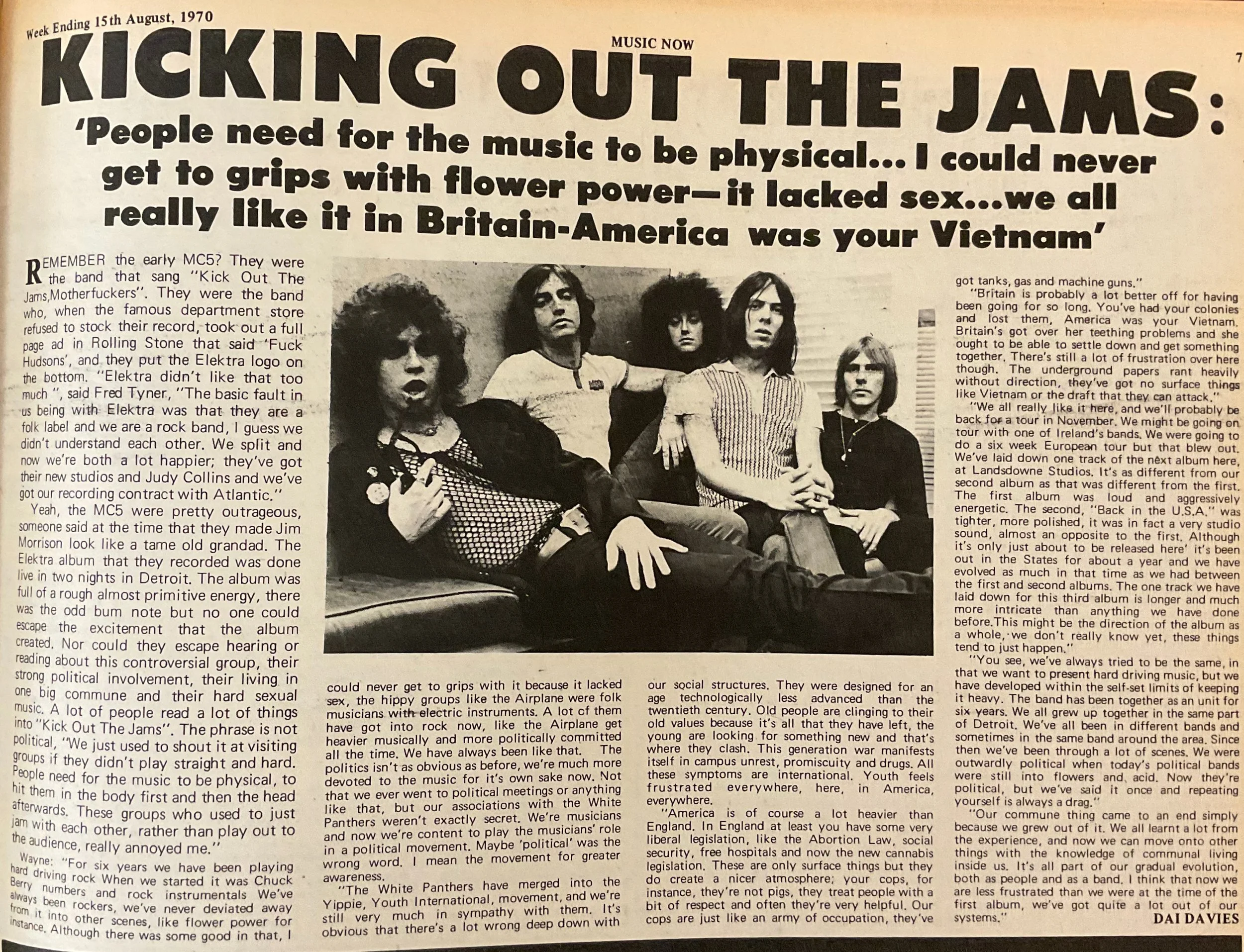

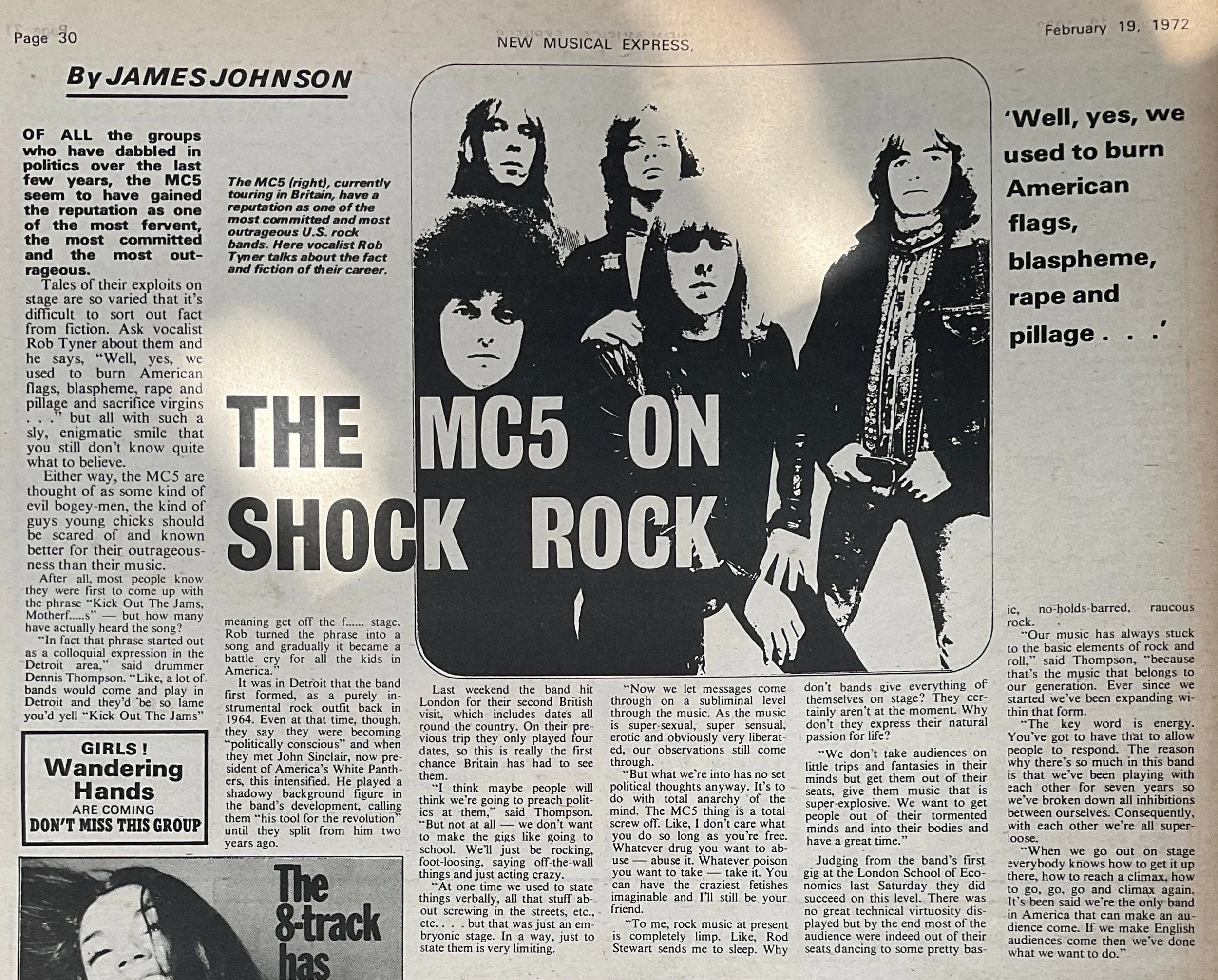

Side one starts off in a hurry with the first three tracks but cools it down toward the end with ‘Anyway That You Want Me’ and ‘Girl in Black’. The last of those two songs comes in at just under 2 minutes and is a solid rip-off of The Who (and all the better for that), while the cello and violin accompaniment on the former, at least in my imagination, following Bangs’ lead, leaks into John Cale’s contributions to the more melodic songs of the Velvet Underground and in Nico’s solo work. Side two stays in mood with ‘Night of the Long Grass’ followed by two non-single tracks, both something of beat standards. Bo’s ‘Mona’ is perhaps the longest cut from 66/7 that they recorded, it has an extended, by their standards, instrumental section but, unlike the Yardbirds say, they are not minded to do much with it; very Stooge-like in its focus, I think. Rob Tyner has said the MC5 recorded a cover of ‘I Can Only Give You Everything’ when the Shadows of Knight got the jump on them and released ‘Gloria’ so they turned to the next best thing in Them’s songbook. I don’t doubt the truth of that but Fred ‘Sonic’ Smith’s slashing guitar riff on the Five’s single is a straight lift from the Troggs’ version.