Decal stolen from the Coop’s amazing Ed ‘Big Daddy’ Roth collection [HERE]

Asked to curate the thirteenth issue of the New York magazine Art-Rite, Alan Vega pulled together thirteen found images. A jockey sat astride his mount on the cover; a newspaper clipping of a photograph of a hostage-taker moments before he blows his brains out; a photograph of Elvis on stage circa 1956; a pornographic image of a man and a woman, head in his lap, her legs open stretched across the backseat of a car; a horse race photo-finish; Iggy Stooge, on all fours, naked torso, raggedy-arse jeans and wearing a dog collar (he looks like some surf bum the morning after a debauched beach party), probably taken at Unganos; a seemingly random page from a horse racing magazine; a cheesecake shot of body builder and blonde woman in bikini; another shot of a horse race; the Marvel comic book figure Ghost Rider; Willie Deville and his paramour Suzie; the bloody torso of a male corpse in a mortuary; and a detail from a painting by Joseph Catuccio. Beneath the final image the editors placed the following:

We dedicate this issue to the average American searching for excitement. These images, punked out from the ambient culture, are the touchstones of a new sensibility, icons of the dissipations and strengths of the modern spirit. Let the way of life idealized in these pages bring into your home the romance of the underculture – horse racing, white trash smut, greasy rock ’n’ roll, muscles, motorcycles and the end of civilisation.

The magazine was distributed free on the streets of New York sometime in 1977, its mix of imagery akin to Andy Warhol’s monochrome death and disaster silkscreens of the early 1960s. If Vega’s collection did pull from a pop art legacy its mixing of an iconography of the ‘underculture’ nevertheless suggested the new shape of things formed in Warhol’s wake – a ‘punked-out’ street culture, where suburban runaway juvenile delinquents looking for a kiss or a fix have landed face down – the sweet ride to the Lower East Side. . . the end of civilisation.

On stage Elvis and Iggy suggest a continuity between fifties rock ’n’ roll and the seventies version but also the downturn the form had taken, its dissolution. One of the most memorable graphic images used to promote rebel surfer sui generis, Mickey Dora, was ‘da Cat’s Theory of Evolution’ showing the eight stages of man’s development from the ape ‘Retardess Kookus’ to the pinnacle of perfection ‘Homosapens Mickey Dora’ riding the surf. Vega’s collection has the process going in reverse from Presley leaning over the lip of stage with fans hands outstretched toward him to Iggy Stooge crawling on his hands and knees.

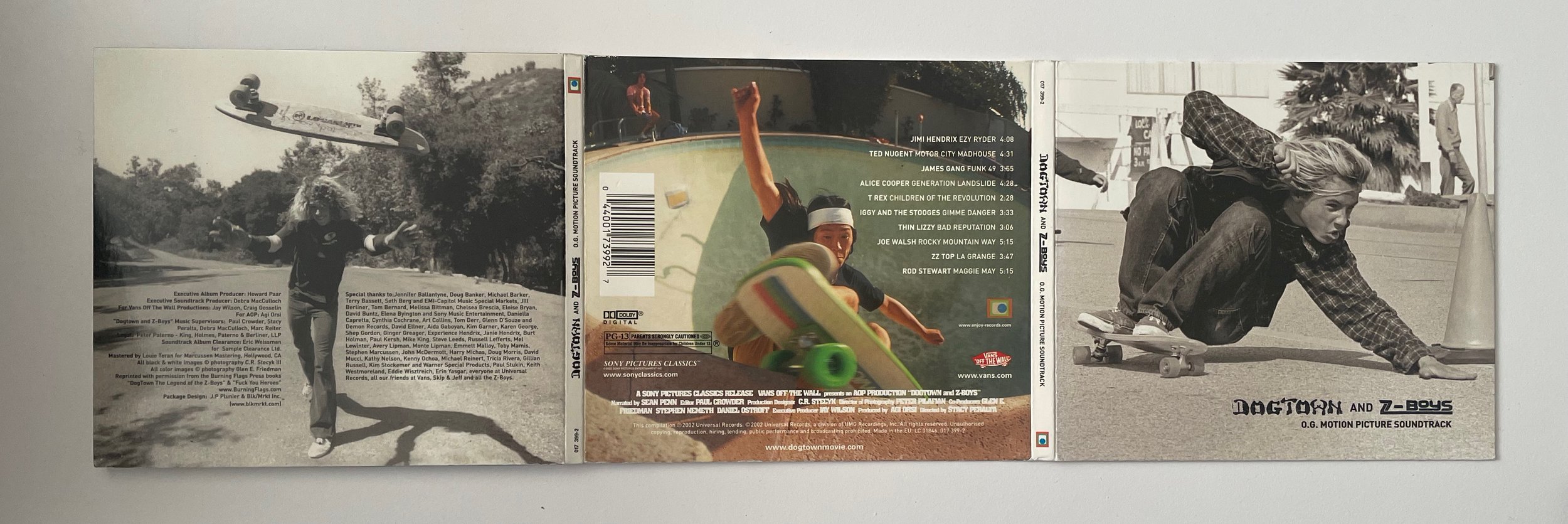

That image of the Stooges as an avatar of rock ’n’ roll’s entropy has become the fixed idea about the band that has travelled down to us through the years, restated in the use of the band’s recordings in films, among them the documentary Dogtown and Z-Boys (2002) later turned into a fiction film, Lords of Dogtown (2005), and The Bikeriders (2023) a drama based on Danny Lyons’ photobook from 1968 with the same title.

Dogtown and Z-Boys is as much about creating a legacy for its protagonists as it is a document on the development of skateboarding as a subculture. The filmmakers themselves were the principle participants, their younger selves the skaters who revolutionised the activity. Director Stacy Peralta, a key member of Zephyr competition skateboarding team, the Z-Boys of the title, and co-writer Craig Stecyk, who was responsible for providing contemporary magazines with the reportage that helped propel a bunch of street kids with attitude into the key figures accountable for modernising skateboarding, are both in front and behind the documentary’s camera – they are their own subject.

During the mid-to-late 1970s the Z-Boys reinvigorated a moribund competition scene, reimagined underused urban spaces as skate parks and remade empty suburban swimming pools into an environment that transformed an activity of mostly linear horizontal movements into a set of abstract vertical actions. They took a leisure hobby and made it into a lifestyle, a worldwide subculture.

Illustrated with a parade of period photographs and 8 and 16 mm footage, the now mature skaters look back and explain what had taken place some 25-odd-years ago – a true insider account, authenticity guaranteed, the story of the team who made skateboarding history. More than that it is a wild ride, brilliantly edited by Paul Crowder. Dogtown’s story is told in a breathless mode, a mobile exhibition on the art of the edit – montaged sequences that mimic the reckless thrill of a series of skating stunts. What aids the film’s propulsive edge is not just Stecyk and Glen E. Friedman’s extraordinary photographs of the young skateboarders but also their use of some 45 pieces of music, mostly contemporary hard rock records, by 30 artists. In 1975 the music would have been a certain kind of teenager’s – those shown in the film – idealised jukebox, one great blast after another.

Opening with Jimi Hendrix’s ‘Ezy Rider’ the film finds an informal correlation between the action shown and the topic of the song, Black Sabbath and ‘Into the Void’, David Bowie and ‘Rebel Rebel’, Thin Lizzy and ‘Bad Reputation’, Pink Floyd and ‘Us and Them’, Ted Nugent and ‘Motor City Madhouse’, T. Rex and ‘Children of the Revolution, all play very similar roles. None though is as effective as Alice Cooper’s ‘Generation Landslide’

. . . la la da de da . . . which is given an extended outing to illuminate the Colgate advertising smile behind which the older generation looks down on their off-spring who are seated among discarded razorblades, needles and other detritus while throwing Molotov cocktails in milk bottles from their highchairs – Alice Cooper’s billion dollar babies, surrogates for the Z-Boys. The two Stooges’ cuts ‘Gimmie Danger’ and ‘I Wanna Be Your Dog’ fill a similar role of soundtracking that generational slide into the void.

While I expect a few of the Z-Boys owned Alice Cooper’s Billion Dollar Babies album or had found ‘Generation Landslide’ on the b-side of ‘Hello Hurray’, so that recording at least was part of their own personal soundtrack and no doubt they did attend parties where Bowie and Rod Stewart were played and Peter Frampton and Aerosmith would have been radio familiars, but I doubt the same could be said of the two Stooges’ records. These were certainly overlooked by radio at the time and therefore unknown to teenage So-Cal listeners, and yet the Stooges sound entirely apposite, perfectly placed, the ideal musical accompaniment to the shots of abandoned and derelict amusements that ran along the beach fronts of Dogtown.

That stretch of Santa Monica with its pre-war piers and leisure parks has become a junkpile of twisted steel, cracked concrete and blasted asphalt. The post-war promise of baby boom plenitude – beach blanket parties – has been transformed into a teenage wasteland – and became a surfer and skater’s playground. The kiss of an ocean breeze in ‘Gimmie Danger’ that Iggy sings about, coupled with the messed up, lovelorn, protagonist of ‘I Wanna Be Your Dog’ – a deadbeat figure to mirror the new decade’s dead end kids – are used to emphasise the idea that the skaters are living in the wreck of society. It is here, out beyond the law, where the kids have made their own culture. They did this, as one of the doc’s talking heads said in that space where the ‘debris meets the sea’ – paraphrasing Iggy Pop and James Williamson’s ‘Kill City’.

Even though the use of the Stooges demands a level of historical reinvention that is not the case with the two Led Zeppelin tracks from Presence that appear toward the end of the film, the fact that the Michigan band make a more notable appearance, create a bigger impact than Jimmy Page’s combo, is because they were constructed out of the same raw materials that the skater’s made their world from. By seemingly being ignored back in their day, the Stooges’ outsider status compounded a negationist sensibility – the ‘no’ to the Americann ‘yes’ – which gives them an authenticity that a band like Aerosmith can only gesture toward. Like the Dogtown skaters the Stooges are the real thing – born dead losers who become winners.

(The fictionalised version of the documentary, Lords of Dogtown (2005), stays true to the original soundtrack though less impactful, more subliminal. The two Stooges tracks are ‘TV Eye’ and ‘Loose’.)

That image of the Stooges carrying the charge of a generation in freefall is there once more on the soundtrack to The Bikeriders. It’s a film like Dogtown and Z-Boys that flirts with authenticity. It is filled with the kind of pop and blues one might imagine cluttering up a jukebox in a biker bar but is much too self-aware to be the real thing. When the Stooges come bowling in with ‘Down on the Street’ it is to mark the characters’ end of days, with hard drugs ripping through the gang’s comradery and its leadership challenged. Play The Stooges or Fun House while flicking through Danny Lyon’s book of photographs and interviews with Chicago’s Outlaw MC, published in 1968, on which the film is based, and you have a seemingly perfect corollary between the book and the record, but it is one that has been learnt – it was never a given that the two might co-exist.

Also filched from the Coop’s collection (and as worn on a t-shirt by a Birthday Party-era Nick Cave

Films like Dogtown and Bikeriders actualise the links that were once hidden or muted between the Stooges, hoodlum cyclists, surfers, hot rodders, rock ’n’ rollers and their Kustom Kulture supply sergeant, Ed ‘Big Daddy’ Roth. Back then, no one hired the Stooges to appear in a party scene in an outlaw biker movie, or licensed their records for the soundtrack, they weren’t catered to by Roth like he did with the Birthday Party, providing the illustration for their Junkyard album (1982) or by his peer Robt. Williams, who did the same for Guns and Roses’ Appetite for Destruction (1987), though conceivably they might have been.

The undertow created by the use of the Stooges on the Dogtown soundtrack ensures not only the now familiar thrill of hearing authentic 1970’s punk music before the fact of the Sex Pistols or Ramones but it also gives to the filmmakers and skater’s legacy an added layer of hip, a cool façade that is a wholly retrospective gloss. The knock on influence of the use of the band’s music in such films is that future movies about born losers that don’t feature the Stooges’ wah-wah throb on their soundtrack are all but unimaginable. The band have now been moved from the margin to the centre, outsider icons whose image on t-shirts sell in shopping malls like Roth’s once did in Woolworths.

As for Alan Vega he and his partner in Suicide, Martin Rev, they made their big screen impact this year in Civil War with ‘Ghost Rider’ a fitting soundtrack for the end of days. America’s alternative anthem, ‘Dream Baby Dream’, played over the closing credits. Bruce Springsteen’s cover of the later had been previously used in American Honey (2016)