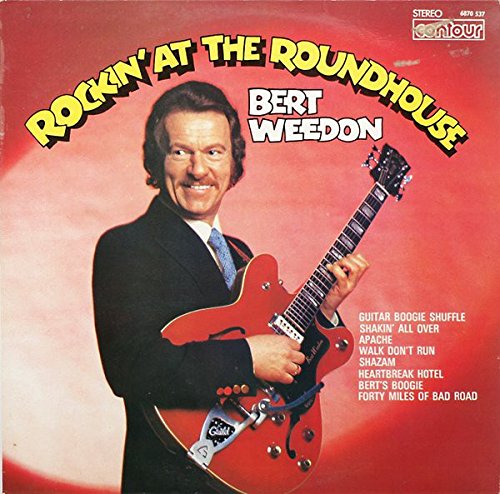

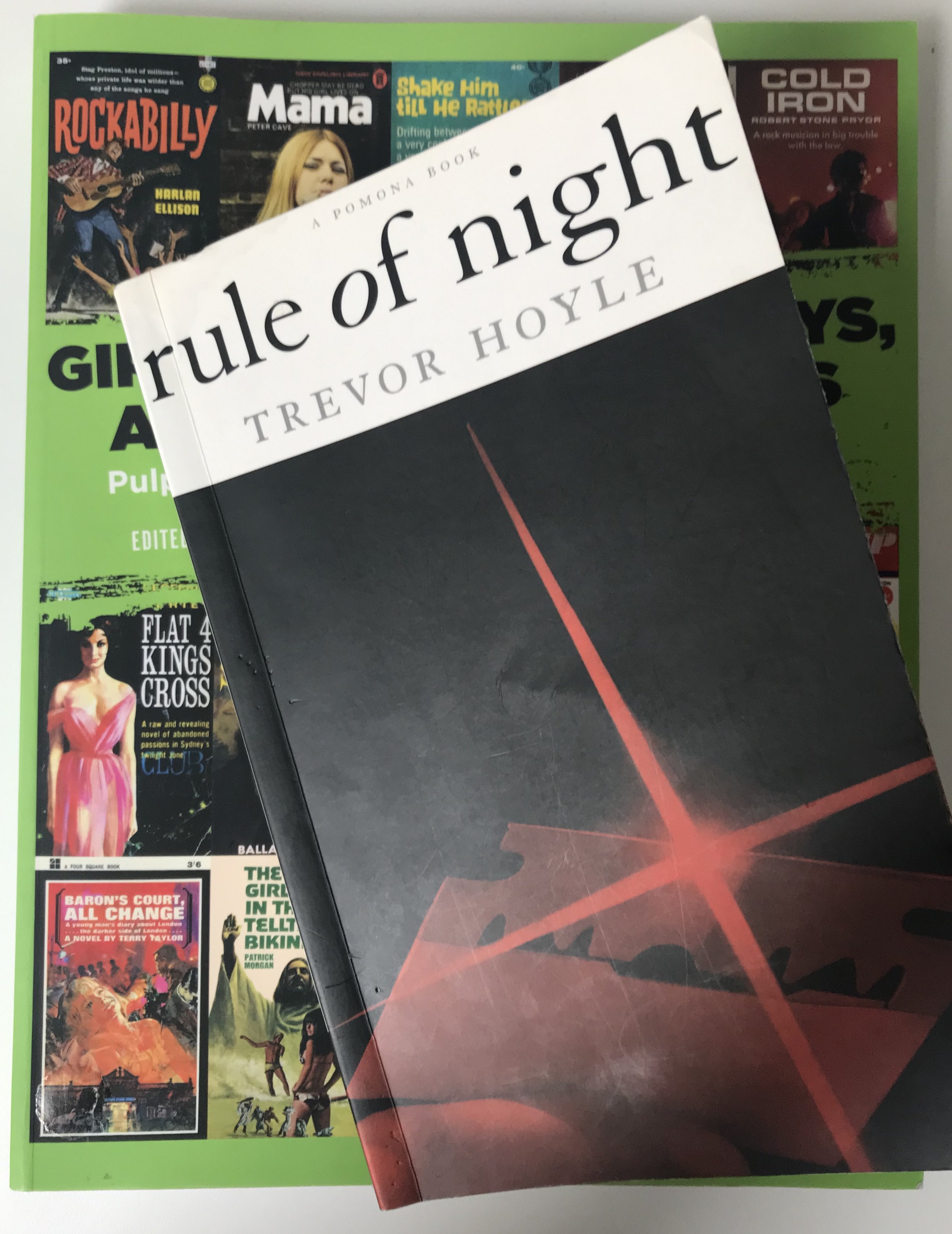

Trevor Hoyle Rock Fix (Futura, 1977)

I’m no expert but this has to be among the best rocksploitation novels of the seventies. Hoyle was author of Rule of Night (track down to May 9th 2019 entry to see what I have to say on that) a novel that puts weight without pretension on the boover boy cycle of pulp originals. Rock Fix effortlessly aims to do the same with the pop exposé.

This is the story of The Black Knights, five northern lads on an endless grind of working men’s watering holes – Hanlan’s Drop Forgings’ Social Club among the more memorable – whose fortune changes for the better (or maybe not) when they meet the pint-sized Phil Martins who helps them get hit records, adulation and drug addictions. The price of fame is high and payment is not long deferred.

Hoyle has an easy almost invisible style to his writing, he’s unobtrusive with a sharp eye for detail, especially the everyday. Past midnight at the Dornan Hotel, Scarborough, the band try getting something to eat:

‘Would a sandwich do?’ the woman said, placing two keys attached to numbered blocks of wood on the desk.

‘Yes. Thank you. What kind have you got?’

‘Cheese,’ the woman sad, and stared him out.

‘I’ll have cheese,’ Ric said.

‘Make mine cheese,’ Dave said.

‘Can I have cheese?’ Andy inquired.

‘Cheese for me,’ Johnnie said.

‘What about you?’ the woman said.

‘Pardon’ Dice said.

‘Do you want a sandwich?’

‘Yes.’ Dice said. He fixed upon her a beautiful smile.

‘Cheese.’

The sandwiches are made of sliced white bread, Stork margarine and Kraft cheese slices and there’s not even a tin of Tartan bitter to help sluice it down.

When the band cut their first record they undergo a name change – God’s Gift – are restyled – white suits – and given a marketing angle to match the theme of their single about a northern girl in search of the bright lights who ends up working the streets. A promotional film and the problem of getting such material on TOTPs is discussed:

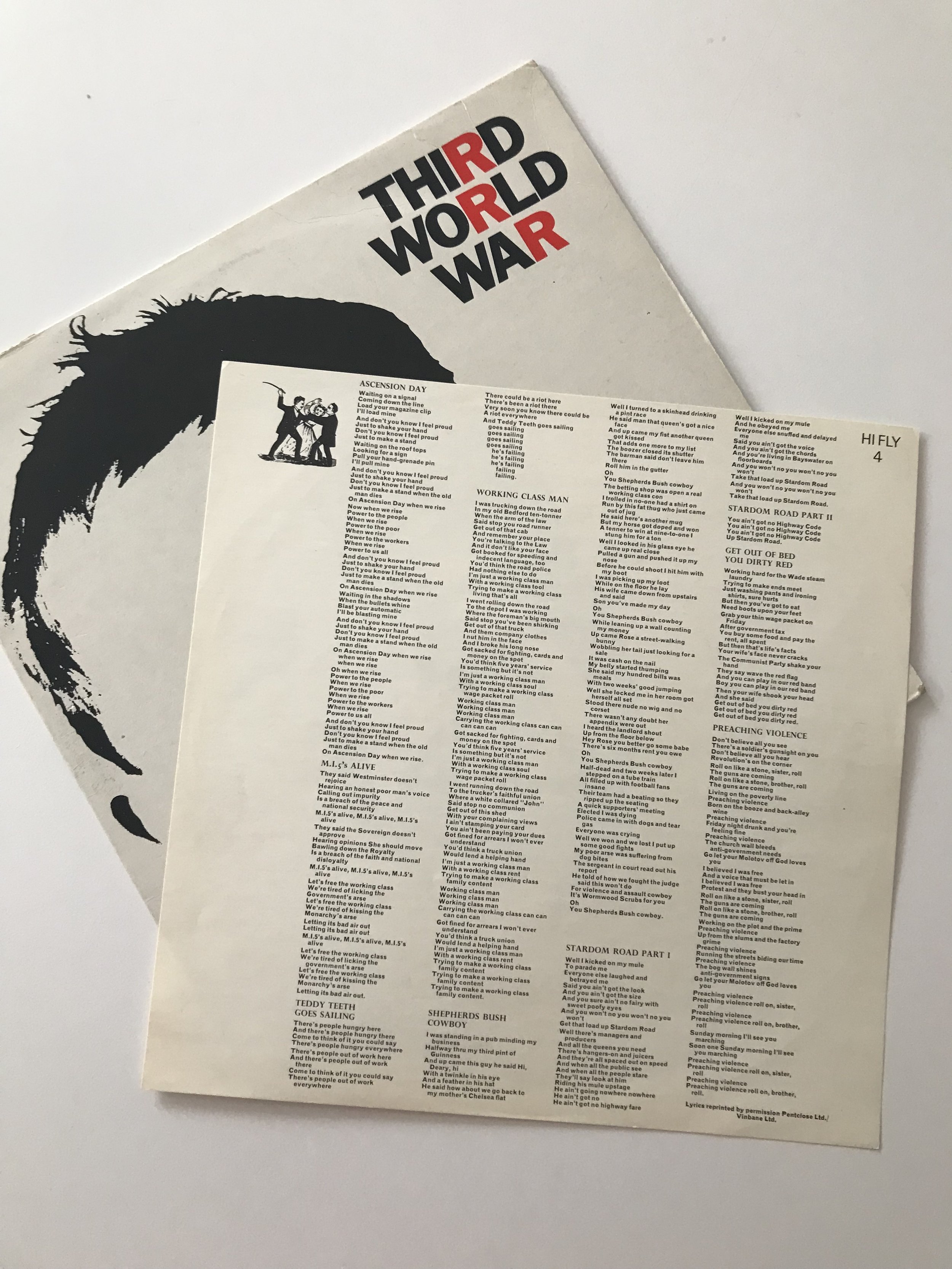

It’s time they did something with a bit of gut feeling instead of all those films of pooves walking through forest glades with sunlight in the branches,’ Norman Fowler said. He sat forward. ‘That’s the tack we’ll take. Social realism. A band with something important to say, a moral viewpoint. Get clean away from all this glam-glitter crap and hit them with a social statement. I can see it coming together – a Dylan-style approach but relevant to the ‘seventies. Social problems. Social statements. Social commitment.

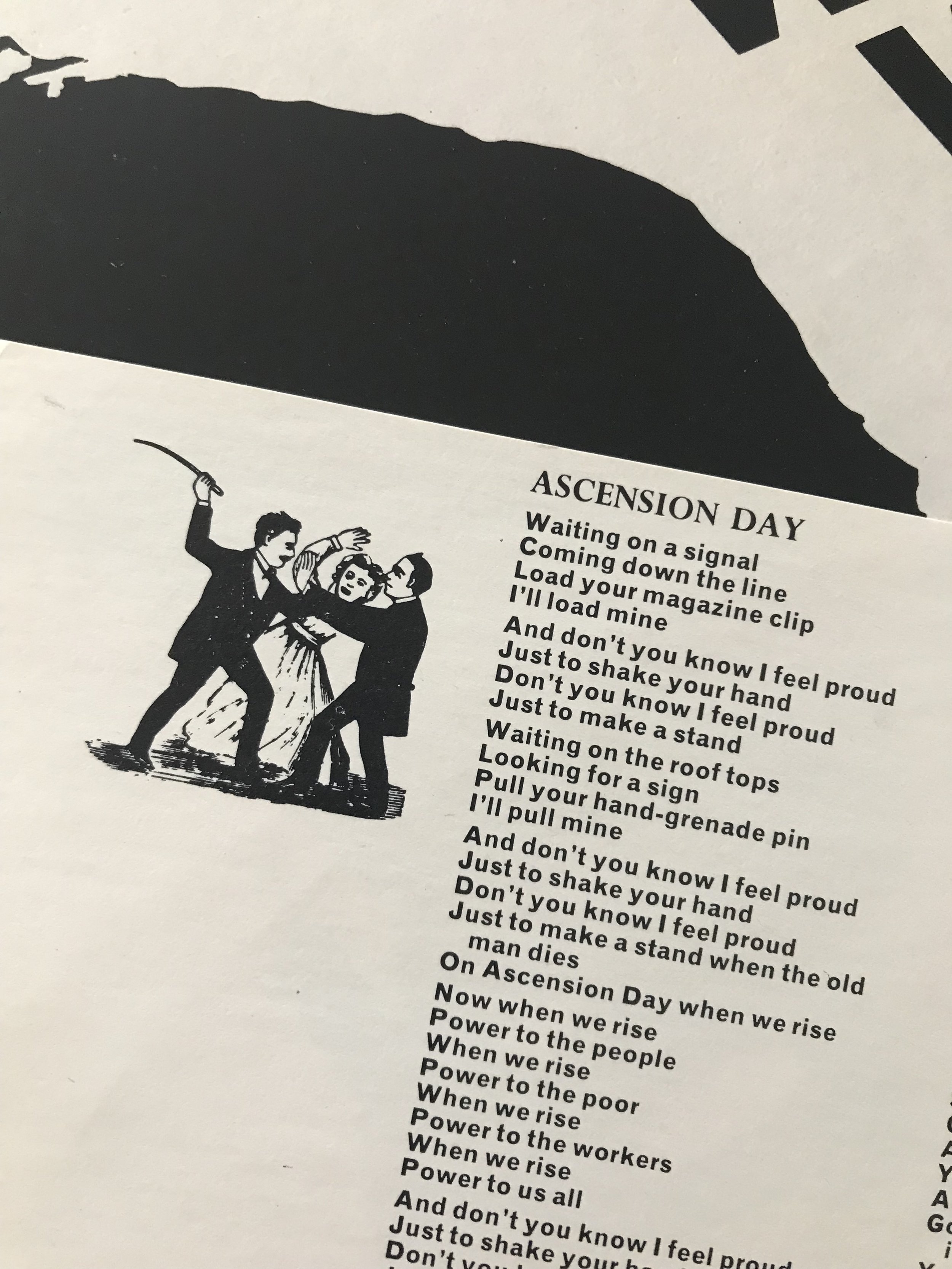

No doubt written before punk had claimed any public attention, Hoyle puts the politics of the Edgar Broughton Band into the pop mainstream but then reveals the shallowness of the conceit when the band confect a four part concept album and their management talk of an American tour supporting Jethro Tull.

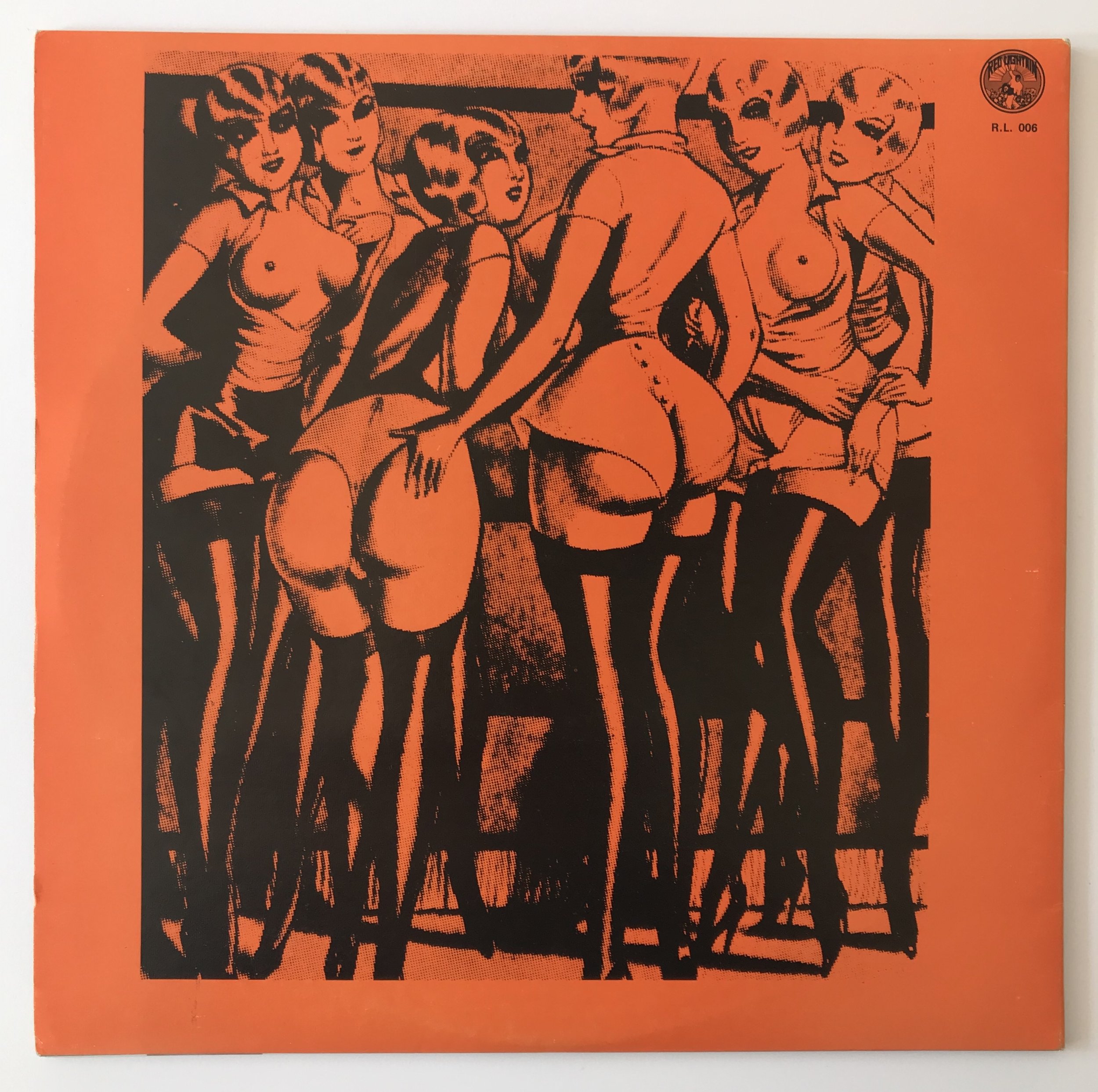

In keeping with the cover image, there’s lots of sex talk (and some action). Most of it takes place in the back of the band’s van, sometimes in an alley. It is always coarse and desperate stuff, no love, no romance, no sentimentality. Hoyle captures the group’s casual misogyny and racism, which he never overtly condemns, but leaves the reader with little doubt where he stands on such commonplace matters.

There’s no rock ‘n’ roll flash on display here, no Bowie or Bolan stars in the making, just working-class lads bonding together on stage and at the bar in the Sunderland Boilermaker’s Club who almost get what they wanted.