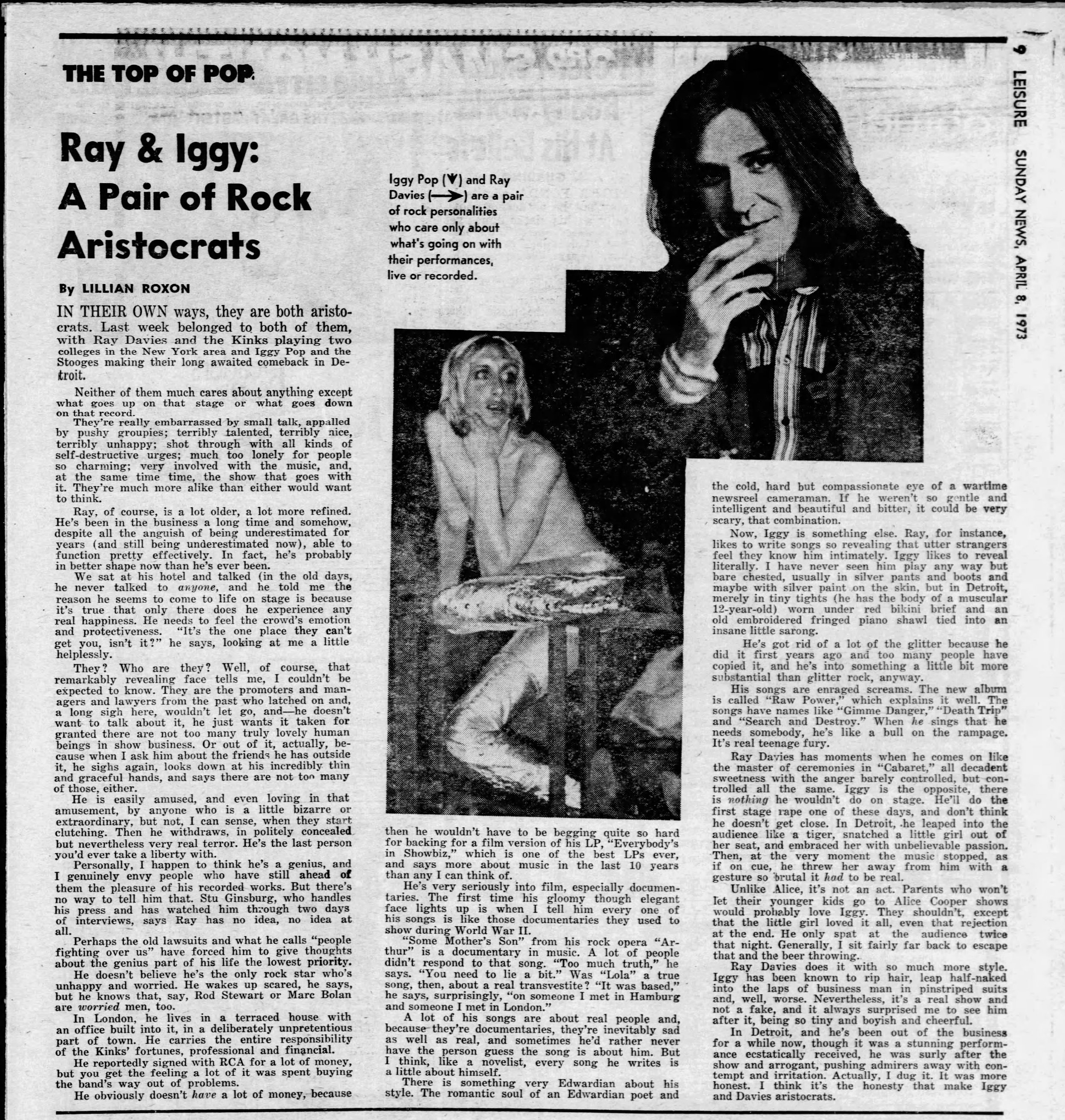

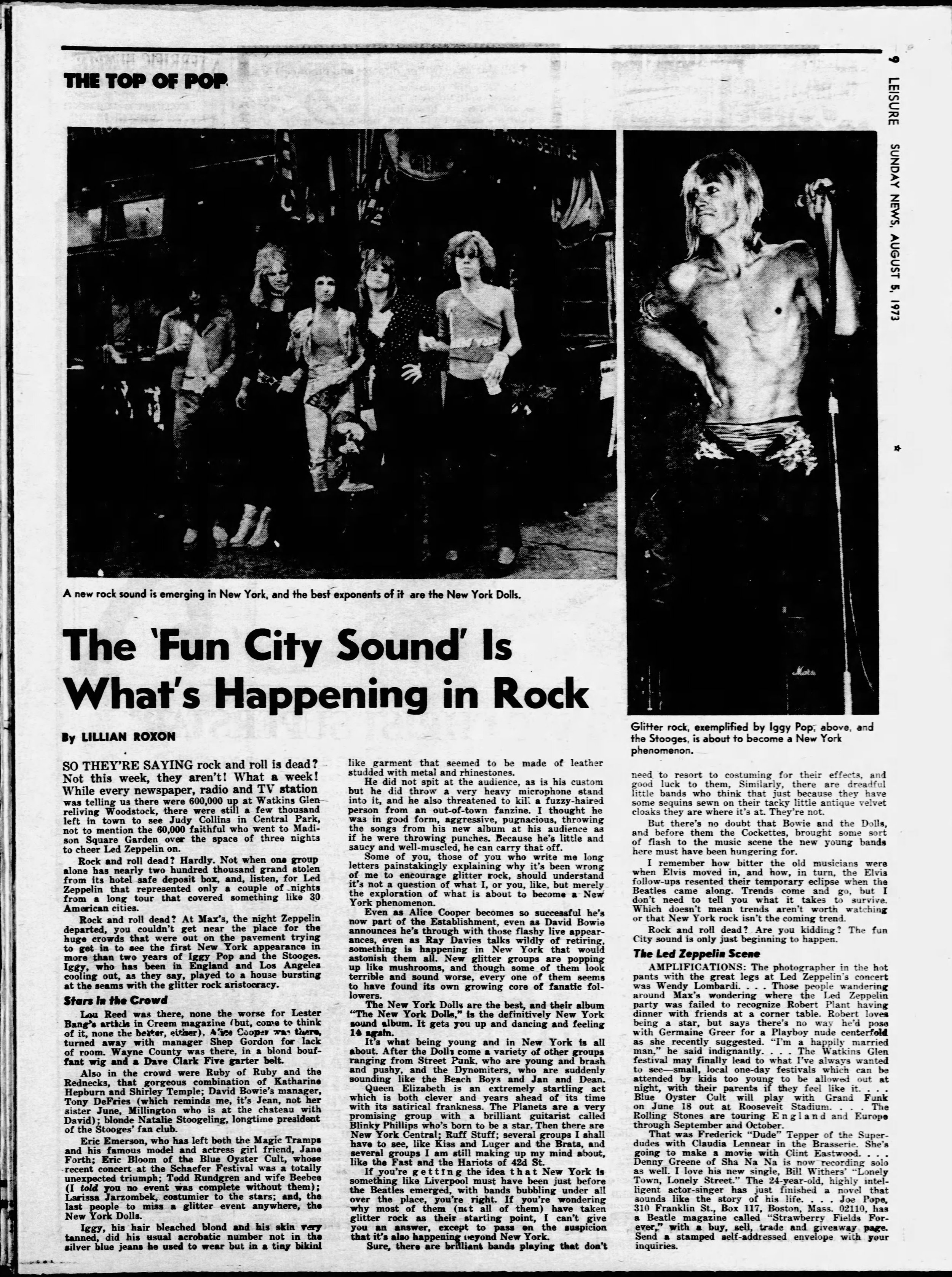

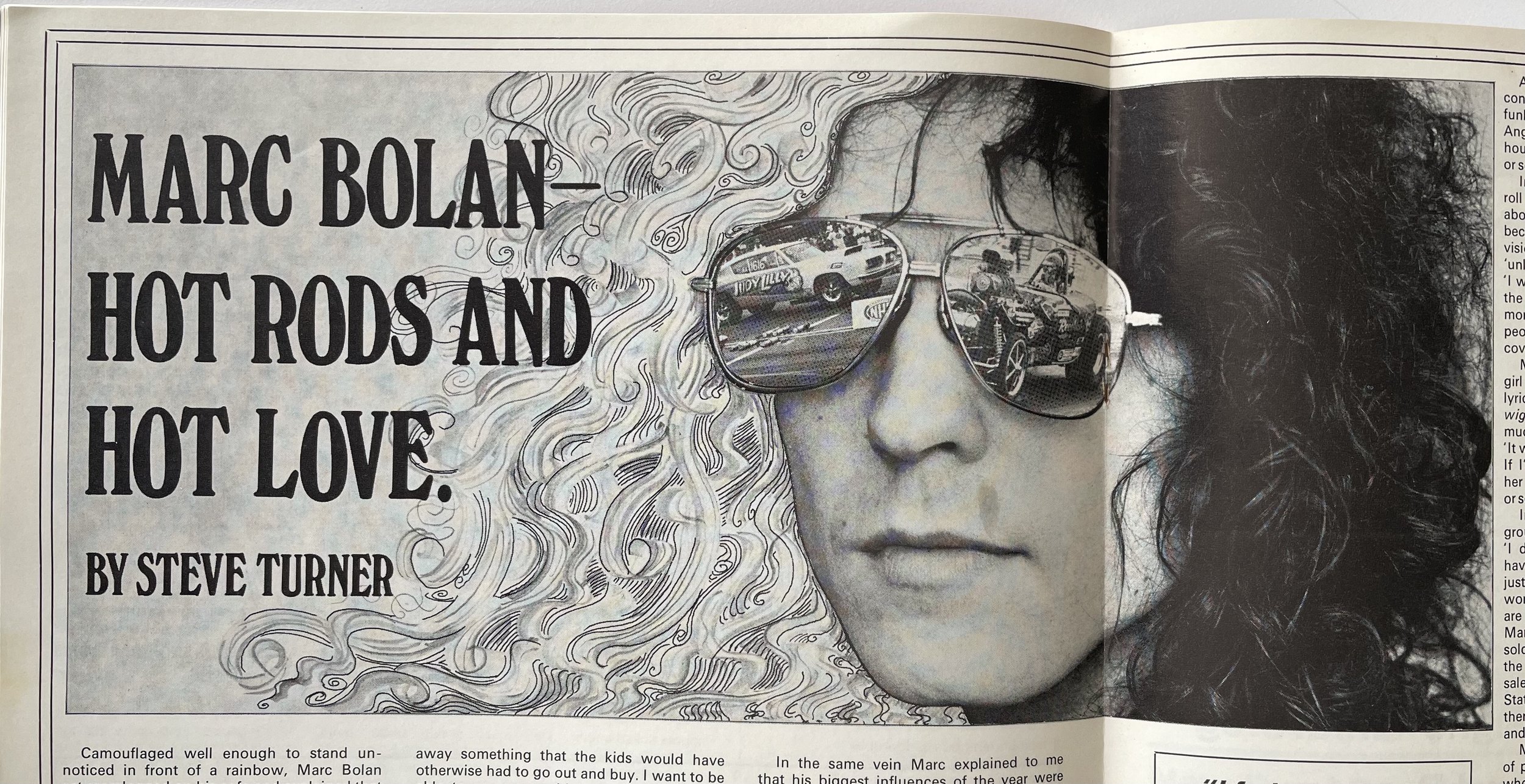

As 1972 moved into the Spring, Lillian Roxon had fallen in love again with pop and the teenage dream. Marc Bolan was her first true love of the new season.

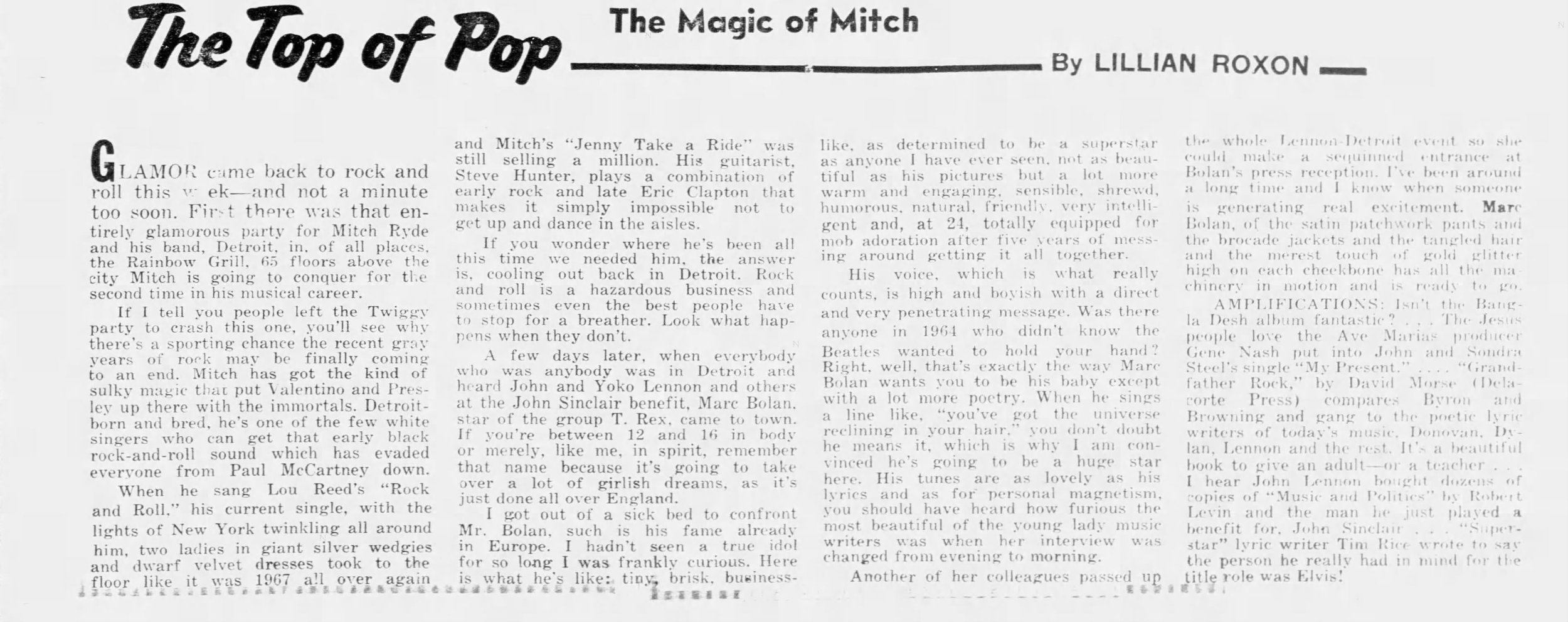

Sunday News (December 19, 1971)

Climbing out of her sick bed, Lillian sets off to meet her new teen idol. She is enchanted . . .

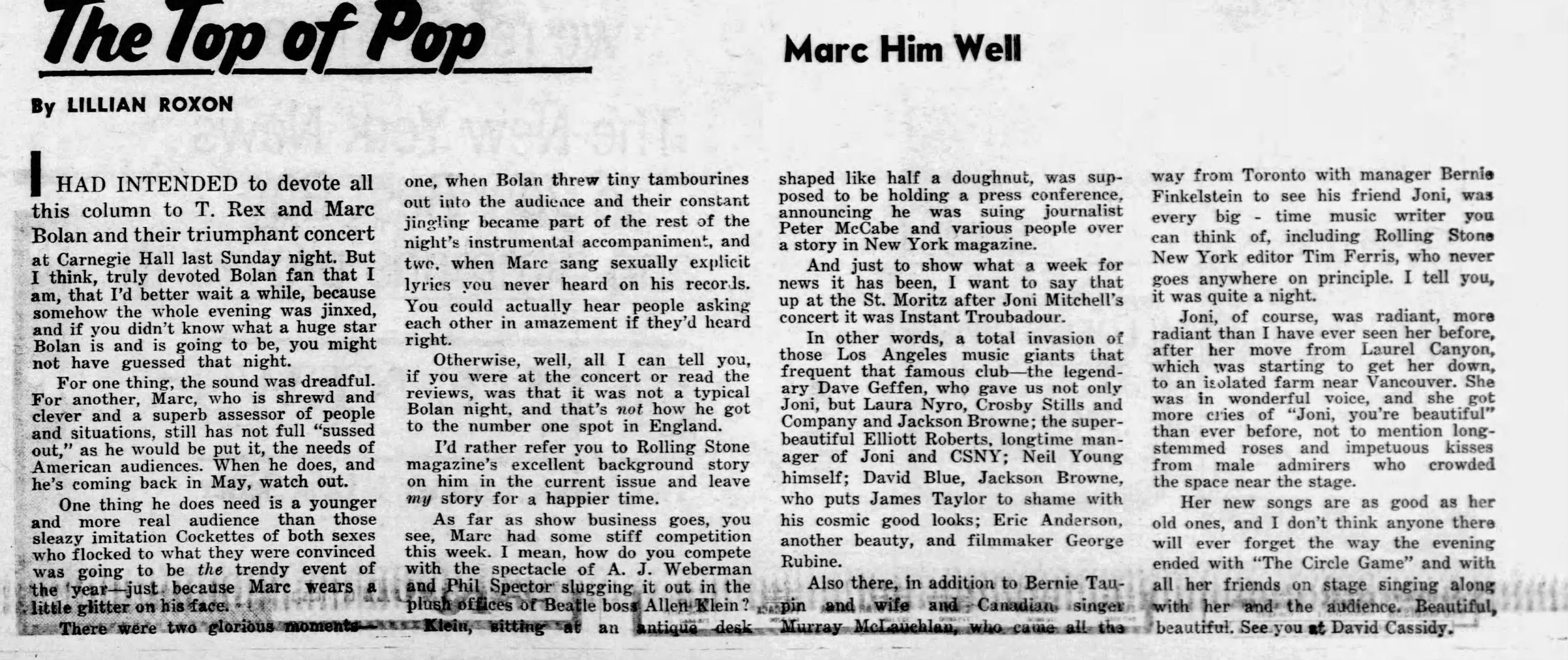

Sunday News (February 20, 1972)

She’ll make at least two trips to London in 1972, in February she was part of the media circus to witness Bowie’s coming out as Ziggy Stardust. The Garbo look has been replaced by short-hair and Star Trek jumpsuits. . . ‘restoring a little of the stud image he’d lost’. The Lou Reed influence on Bowie is pushed to the fore

Sunday News (February 27, 1972)

When in London, go shopping . . . This represents perhaps the earliest US press appearance of Malcolm McLaren and Vivian Westwood’s Let It Rock. Lillian calls it Paradise Garage, which had ceased trading in November 1971. The confusion is understandable, as Paul Gorman reminded me the Let It Rock sign was not in place until March ‘72.

The salesmen have long hair, all right, but it is greased back into high shiny pompadours. When they’re not wearing motor cycle jackets they sport authentic drape shape coats with velvet lapels.

Sunday News (March 5, 1972)

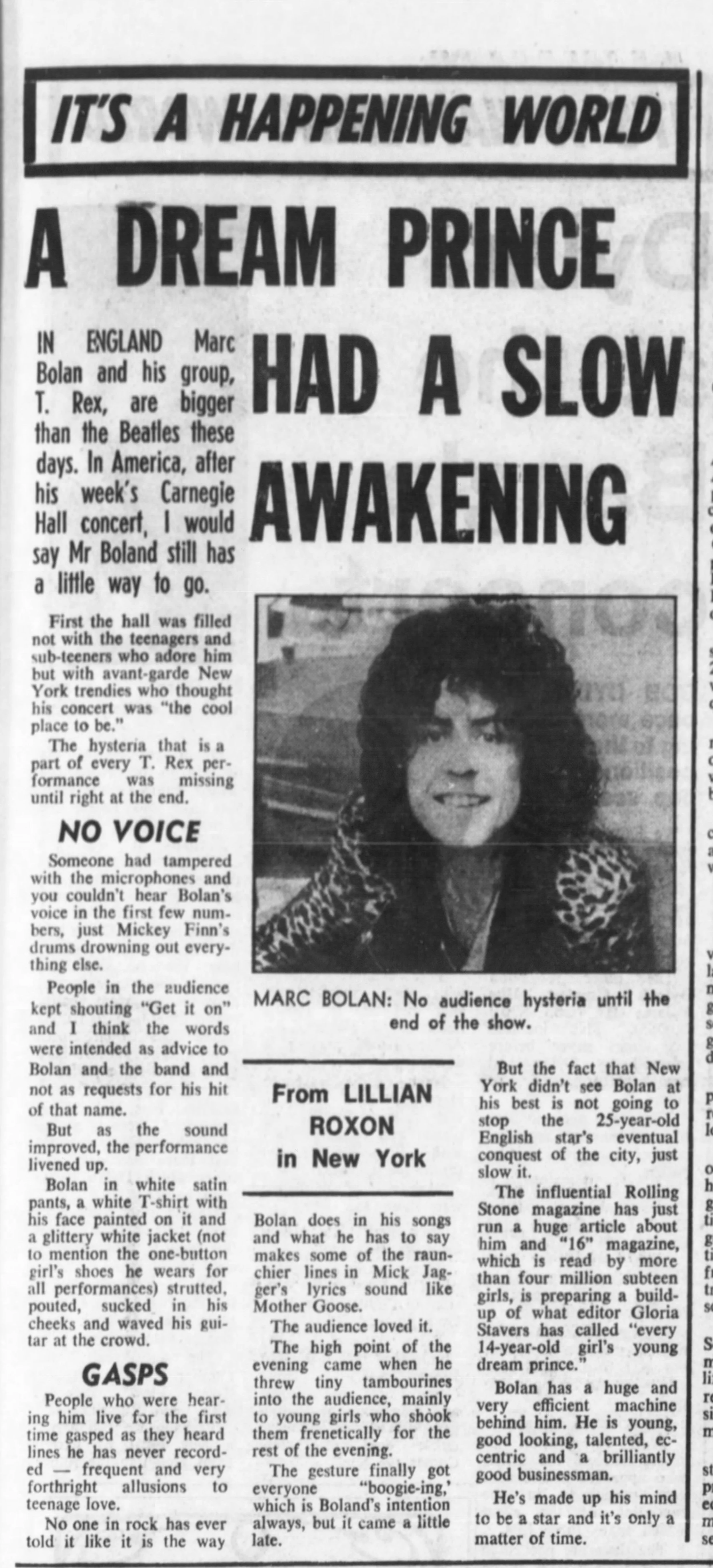

Bad sound and the wrong audience spoilt Lillian’s enjoyment of T. Rex’s Carnegie Hall gig. In her two accounts of the show she mentioned Marc ad-libbing sexually explicit lyrics: ‘You could actually hear people asking each other in amazement if they’d heard right’. So, what was he singing? I need to know.

Sydney Morning Herald (March 5, 1972)

Sunday News (June 18, 1972)

In June she interviews Bowie during a 3 day promotional visit to NYC. Both watch Elvis. Bowie plays on the idea of being a fabricated pop star, imagining a doll in his own image with hair that grows and that can say things like ‘I love you’ and ‘I like to dress up’. Lillian hopes it will come with the full Ziggy wardrobe.

Sunday News (July 30, 1972)

And then she’s part of the press junket arranged for American critics with a Bowie show at Friars, Aylesbury and the Lou Reed and Iggy and the Stooges sets at King Sound, King’s Cross.

Sunday News (August 6, 1972)

Sunday News (September 24, 1972)

Bolan is back and playing at the Academy of Music, but it’s still not working:

this is a man who should never be allowed to work without at least two hundred screaming young girls crammed into the first ten rows . . . Playing to the torpid mob at the Academy of Music, he was like Raquel Welch trying to do a strip for the Daughters of the American Revolution. Namely, not fully appreciated.

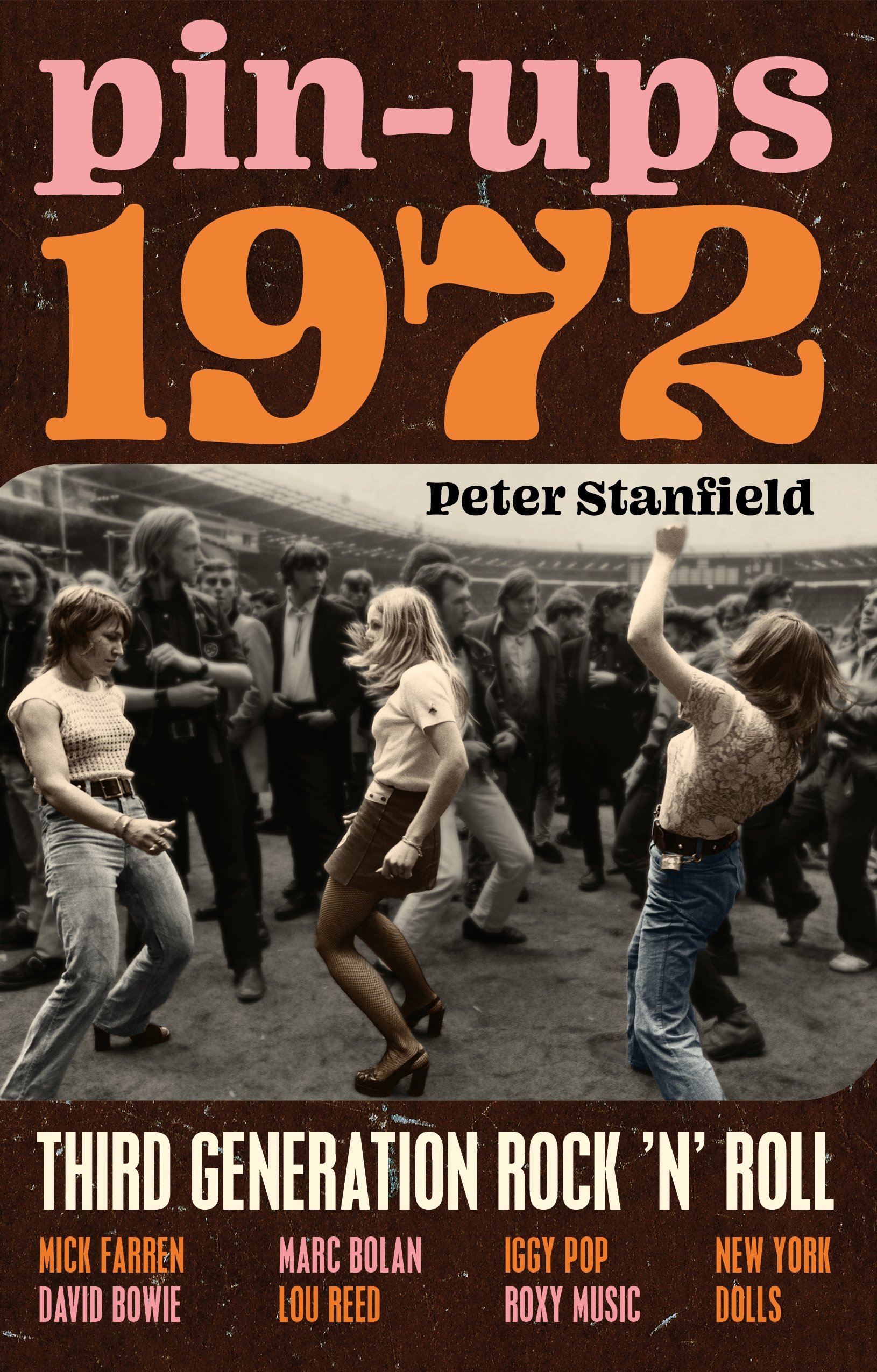

Meanwhile, Bowie is about to make his debut US appearance . . .

Daily News (September 30, 1972)

A star is born . . . whose ‘carefully stylized movements give us an updated (though deceptively frail) ‘70s version of the ‘50s teenage hood’.

Sunday News (October 8, 1972)

Sydney Morning Herald (October 8, 1972)

Sydney Morning Herald (December 10, 1972)

Lou Reed given the ultimate plug for his forthcoming Transformer . . . evil