Tosches’ oxymoronic intellectual primitivism took appreciable form with his sprawling essay ‘The Punk Muse – the lowdown on grease’, first published in Fusion and then collected in Twenty-Minute Fandangos. His point of departure was a critique of ‘honky bluesmen’, young white middle-class musicians who want to play black but can’t because they are not the authentic thing itself:

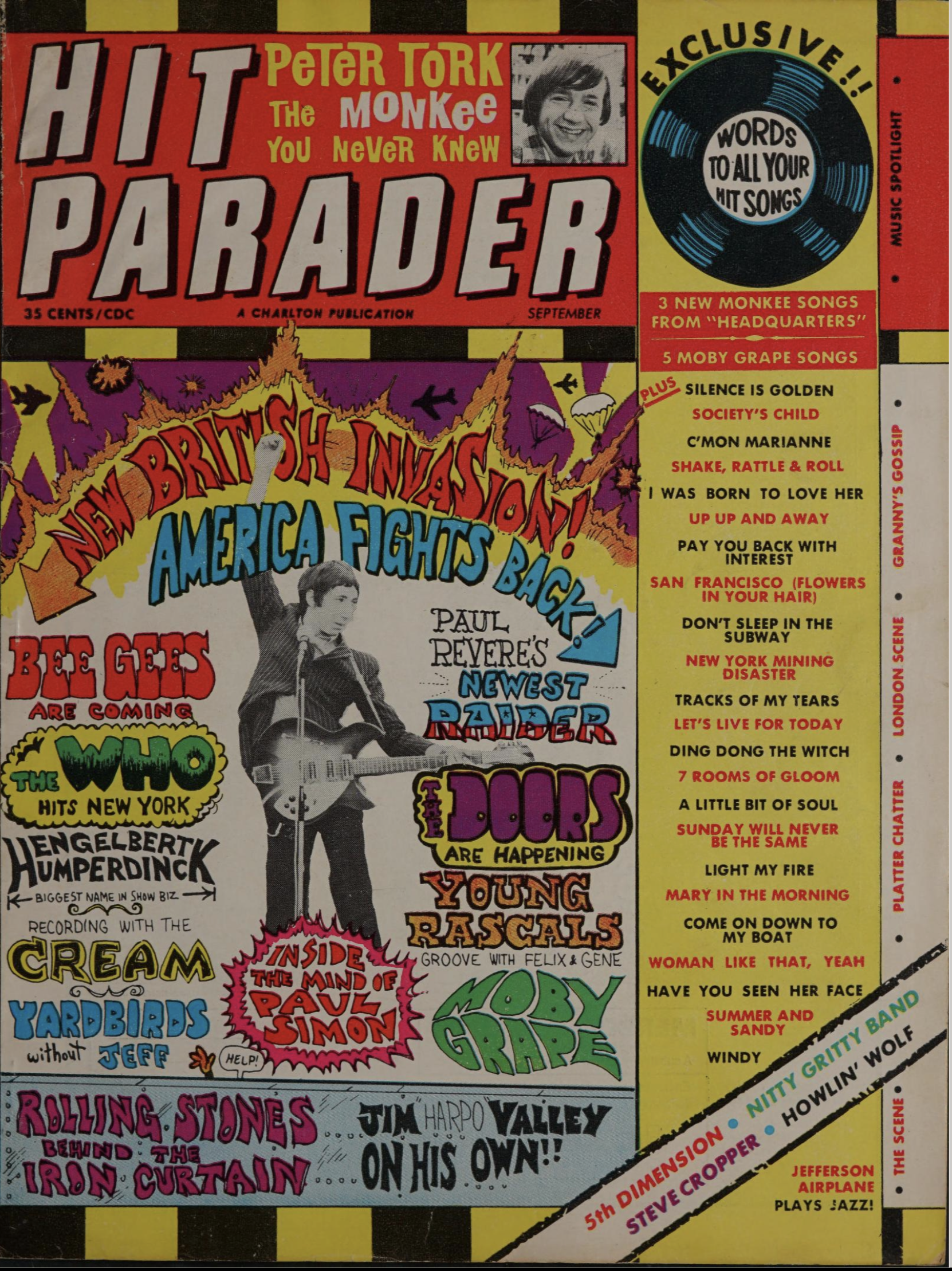

A straight Honky Music (Honk2) scene is a thing where you have a bunch of guys with teased hair up on a stage doing black blues, singing, with admirable ventriloquial skill, like Howlin’ Wolf in the throes of a Dexedrine orgasm, to a mob of suburban quasi-virgins who compensate for their fear of sex by substituting ‘The Lemon Song’ by Led Zeppelin at a distance of eighty paces for a good stiff dick in the dark meat.

Those who perform and listen to such acts of mimesis are ‘punks’, the honk squared is their muse. Contrary to this aspiring but lowly type is the ‘Grease’, exemplified by The Cleftones, who knew they would never know:

They knew that the secret of the universe was up in Betty’s drawers and in no one else’s. And they never got to know the secret. So they stand, left foot forward, in a timeless void, forever recreating that moment when Gnosis squirmed and said, ‘I’m not that kind of girl’. . . Grease tropes like that, sublimating the electric theme of unrequited love to dazed unrequited hard-on and back again, cultivating it with the lethal dronings of the honk fuck ritual choreography, are heavier and deadlier than anything the Stooges are capable of calculating. That’s because it comes from the heart (id) and not from the ego; poetry is puked not plotted.

As he overlooked Margate sands, T. S. Eliot would have been at odds with Tosches’ formulation, but, with their spitting, The Stooges would have slipped right in alongside The Cleftones. Except, on Tosches terms their artifice excludes them from the canon of Grease. The Cleftones were ‘speaking from the heart’, he wrote, ‘from the inside out as opposed to the I-wish-this-were-the-inside out’, which is where The Stooges did fit in. They are punks, a lesser form, lower on the scale to grease because they are a confection.

Tosches may have rejected The Stooges as ego not id, but the band were a good mirror to his own aesthetic:

Other great Honky Bluesmen of the Golden Age of Classical Grease were the Clovers, who drenched their melodies with the rhythms of the collective foyerfuck of a generation, bead-rolling the surroundings of sex memories and inducing minor key orgasms in parking lots throughout the nation, and the later female vowel-jobbers, Shirelles and Shangri-Las (although they are, in a strictly chronological sense, denizens of the Early Decadence), holy queens of greasefuck poesy, transmitting osmotic tau-waves of epiphanous pussy stench through silver-sequined lamé and jet-black stretch pants, moaning at America's youth for a transubstantial clit-strafe in the time-warp of adolescence. Kiss me there, Billy, kiss me there . . . (Ronettes, early liberators of Sleaze, unsublimated sex) fingertips (odors) . . . There, Billy, there . . .

Tosches’ vulgar turns are as learned as any stanza in The Wasteland, as are his arcane allusions and his shifts from the vernacular to the cultivated, from the profane to the sanctified. Yet Tosches is no more T. S. Eliot than The Stooges are King Crimson.

Opposed to the ‘Classical Grease’ were ‘THE NITWITS. Alias the Assholes. Those who sweetened sex. The Valentines, Playmates, Penguins’. But the Grease could not be suppressed or sanitised, it rolled on. To make his point, Tosches takes a detour into the realm of mathematics, into ‘The Metalflaked Alephteriaries’. The compound of ‘aleph’ and ‘teriaries’ belonged to Tosches alone, but no one, least of all the author, expected the reader to stop, pause and consider what was before them, only to wonder at the display of erudition as he traverses three forms of infinity. His final formation:

One who deals in visions, that is, one who perceives all the infinite rays of one object, or objects of conjugal positions (intersecting rays), is an Alephteriary, someone like the Heartbeats or Eza Pound or Andy Warhol, someone who can make dirt chairs by spilling it the right way. A metalflaked alephteriary is someone who can handle the infinite but, nevertheless, has a little plastic skull on the rear deck of his Olds that, for a right turn, blinks red in the right eye, and, for a left turn, red in the left eye.

Of The Heartbeats 1956 recording ‘A Thousand Miles Away’ – ‘an amazing catatonic blues, which rivals any extant Samuel Beckett soliloquy, with its eternal pledge of “coming home soon”’, Tosches wrote, ‘The basis of the song is the perpetration of desolation by the emission of artificial emotions, the absence of their non-artificial emissions dictating psychotic existentialism’. If this seems more than a two-minute street corner pop record can bear, Tosches provided the (faux) footnote in support: ‘5. See Andrew Duras, “The Year Dionysos Never Showed: A Study of the Heartbeats”, American Journal of Honk/Hieratic Communication, XII: ii (October 1961), pp. 92–117.’ Nothing to argue with there then.

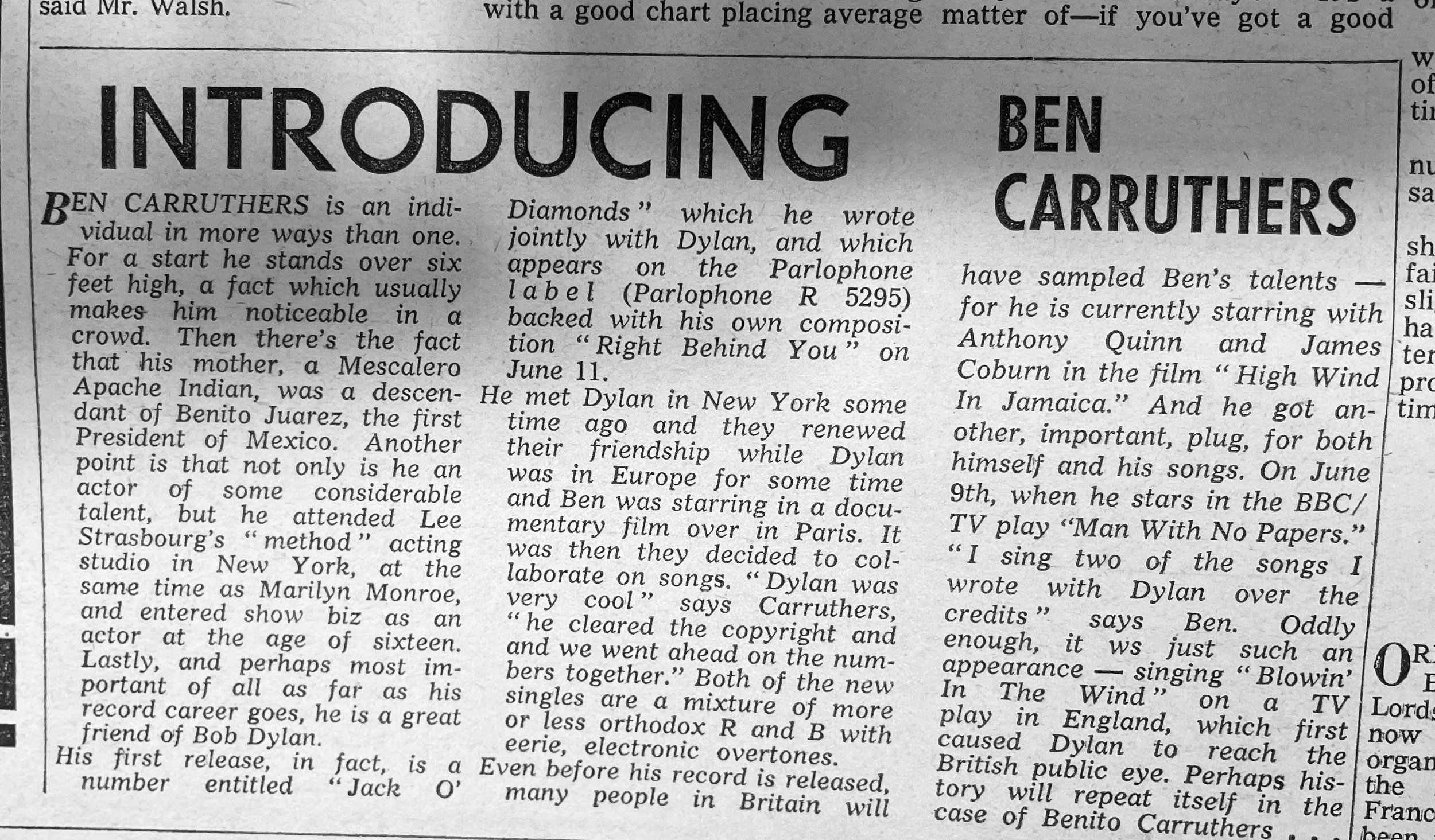

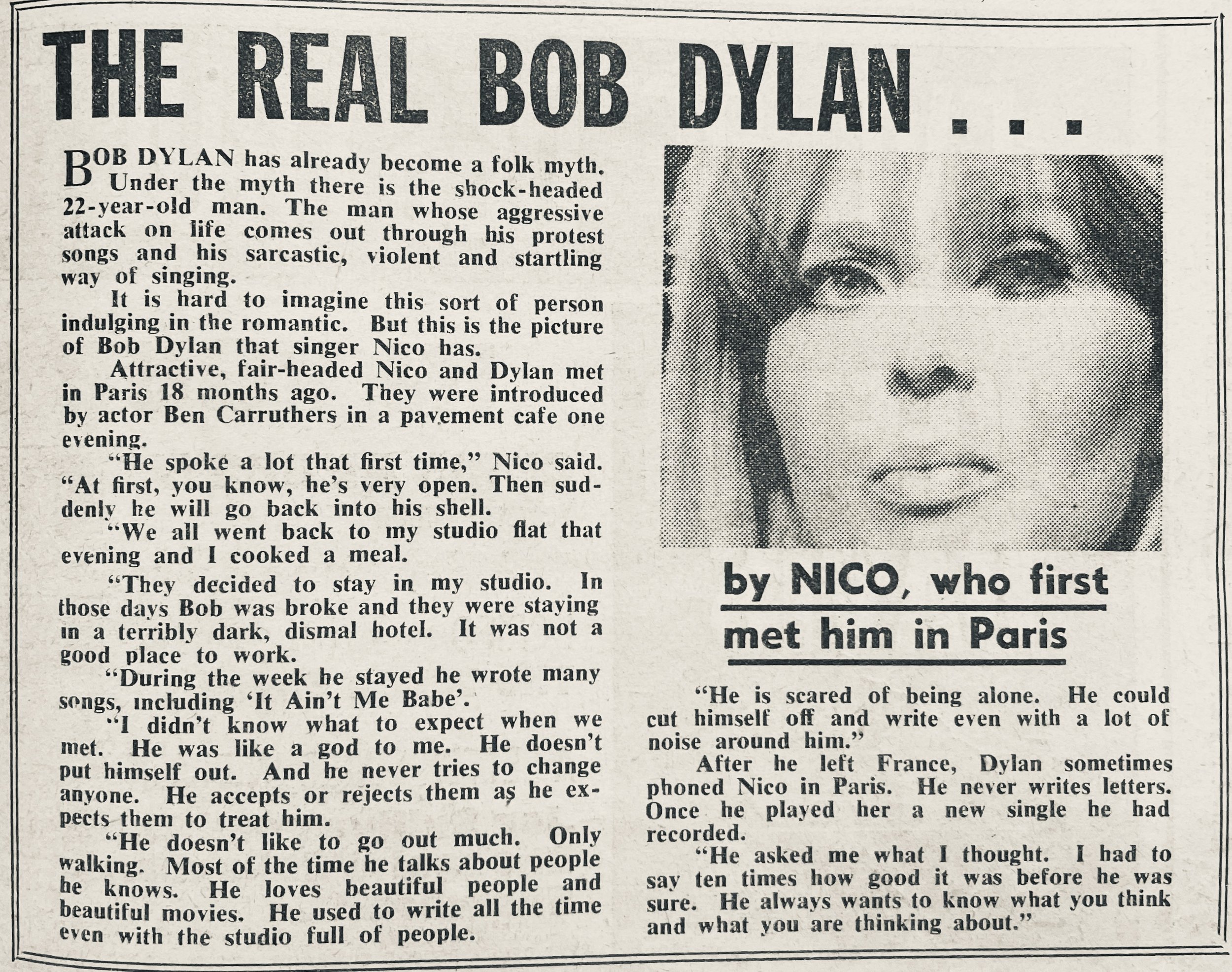

‘The Fall of the House of Grease’, its ‘decadent period’, ran from circa 1958 to 1965, from the tv debut of 77 Sunset Strip to Alan Freed’s death, it was the age of Edd ‘Kookie’ Byrnes, Paul Anka and Leslie Gore. It was a time of superhype, of ‘punk media’, of Fabian and Dick Clark. In this time zone, The Beatles and Bob Dylan emerged, the latter ‘swept up in the then-big folk punk fad’. For Tosches, Dylan’s catalogue up and until Highway 61 Revisited ‘had perpetuated some of the honkiest bullshit in the history of American music. He had sat there with peach fuzz on his chin, singing like a hardened Negro loner about cold death’. That was the outside looking in, all ego, but then with Highway ‘he saw the whole derangement he’d been involved in and he began to spew out things from his own heart, all those things he used to pretend weren’t in him. . . Take ‘From a Buick 6’, a near perfect song, as good as anything the Heartbeats had ever done. Pure alephteriary’. He followed this with Blonde on Blonde, ‘one of the best rock albums of the decade’. The Beatles were similarly late developers into the state of alephteriary – ‘who the fuck wants to hold somebody’s hand?’ – but the combined effect was to win over ‘hordes of Cerebrum Groupies to become intellectual bodyguards of rock, spouting their dissertations of fantastic spiff genius into the nation’s offset presses and lecture halls . . . The Beatles made rock a punk religion’. They turned rock from a ‘calmative’ experience, you could rip it up on Saturday night but for the rest of the week you conformed. In revolt against this order, The Beatles said the rock experience could last seven days a week and ‘incited, albeit mildly, the feeling of discontent’. In doing so they paved the way for the ‘truly culturally revolutionary groups – the Jefferson Airplane, the Fugs, Country Joe and the Fish, even to a certain extent the Doors’.

Grease is the divine state of being, punk is the unworthy aspirant to that holy order, a rank acolyte. Those who solemnised rock, the cerebrum groupies, were punk critics. Meltzer, Bangs and Tosches were the grease who, from the heart, could see beyond the finite. But ‘punk’ and ‘grease’ were hardly separable from each other any more than the id is from the ego, or pure from impure. Writing in 1969 for the Detroit Free Press, Mike Gormley tacitly pulled together the cerebral and the somatic, the intellectual and the primitive, The Stooges were his test case:

The music they play has been described as stupid rock at its best. Iggy calls it dirty music and the group’s manager, Jimmy Silver, says ‘it’s dance music, fun music for kids’.

Iggy expanded on his definition. ‘The music we play is like a ritual we go through. It sounds like elemented rock but it’s actually based on classical and folk themes that are ancient. There’s a kind of bizarreness to it because we felt bizarre. When we play, a lot of things come out intentionally, so that’s the basic thing. It may be the reason our music is extremely moody. It has very simple moods to it.

Iggy as punk prophet and muse, The Stooges a greaser’s manifesto. Tosches wanted the purity of an untrammelled id, his Heartbeats, but they are a fantasy, his own honky blues; he was on surer ground with extolling the impurity of Dylan and Highway 61 Revisited. With The Stooges, Tosches’ had tried to outdo Meltzer and Bangs, dismissing the band they had lauded to establish his hip credentials. In doing so Tosches ignored his own equation: punk + grease = metalflake alephteriary. Such a formulation meant you could convene with Iggy Stooge to testify on the infinite power of the Heartbeats, the one didn’t exclude the other. They were co-dependents. Meantime, without a care for the infinite, Ron Asheton, posed as the ultimate greaser punk in his pink Star of Hollywood shrunken head shirt, Iron Cross and white buck shoes, and pressed the keys on the jukebox selecting once more The Yardbirds’ ‘I’m a Man’.

What the band has to go on is showmanship. Right now their style is so unique that success comes easily.

But Iggy doesn’t seem to care either way.

‘The Stooges were together for a whole year before we even had a gig, and nobody even thought of us as a band. But I didn’t care, literally didn’t care, and I don’t care now. I don’t exalt some format of the band and I don’t exalt its success. If I want some success, and I happen to be in the mood to accept some success, sure, I’ll take it. I’ll grab for it, or maybe throw it away, or maybe I’ll kiss it . . .’

And that’s the word, straight from Iggy.

– ‘A Painful Exercise in Pure Volume’, Honolulu Star-Bulletin (October 12, 1970)

Lester Bangs didn’t make the cut for Twenty-Minute Fandangos, his two glory shots ‘Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung’ and ‘James Taylor Marked For Death’ were published in the same year as Eisen’s volume, but his two-part review of The Stooges’ Fun House, published in November and December 1970 editions of Creem might have been a late contender. Perhaps it was and Eisen decided that he already had enough Stooges. Whatever, it so closely followed the lines laid by Meltzer and Tosches to suggest it wasn’t because the editor was opposed to Bangs’ sermonising.