and that would be Iggy Stooge . . .

I recently picked up a copy of Lillian Roxon’s Rock Encyclopedia, the 1971 paperback edition with a new, very short, introduction that tried to capture how much had happened since the book was first published in 1969. CSNY had formed, Led Zeppelin had become the most popular band in the world, The Beatles had quit and the Jackson Five filled Madison Square Garden (and so did Grand Funk Railroad), but the most significant event was that Iggy Stooge had emerged and she was smitten ‘. . . with the sexiest thing since Mick Jagger’.

The Encyclopedia’s 1969 entry for The Stooges is easily missed as it falls under their longer name ‘The Psychedelic Stooges’. That these unknown Detroit hoodlums get an entry while bands with a history and a profile, like The Pretty Things, don’t make the grade might suggest that her friend, and the explorer responsible for discovering the them in 1968, Danny Fields was getting the hype in early.

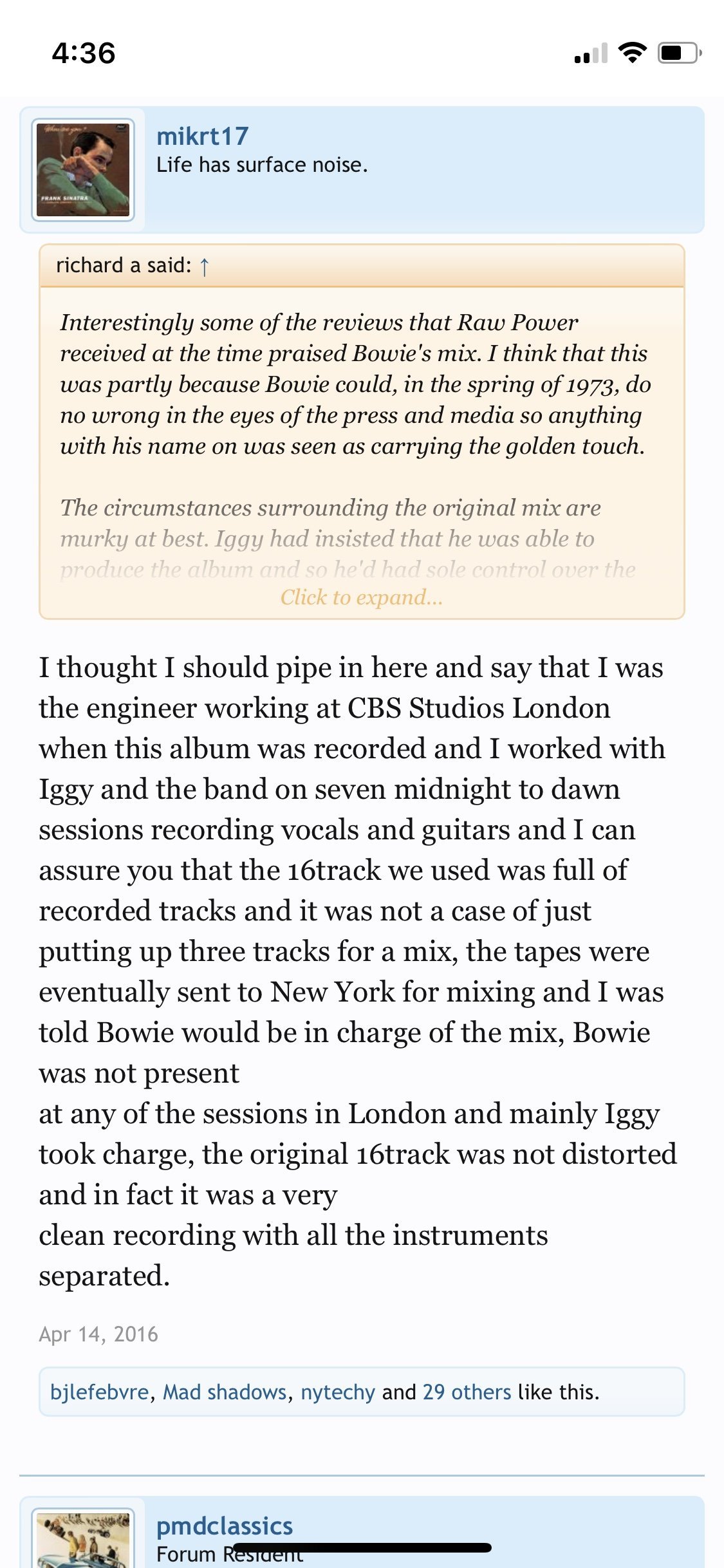

Intrigued, I went looking for some other things Roxon had written about The Stooges. She was the New York correspondent for Sydney Morning Herald so I trawled through the paper’s archive, which gave me little more than the two articles Per Nilsen cites in his estimable Iggy & The Stooges On Stage 1967–1974. Other than those two, the band made a few brief appearances in the paper. Roxon used The Stooges to illustrate one of the directions contemporary music was heading: the theatrical, shock rock approach shared with Alice Cooper. There’s a note that Astor records have picked up the license for Elektra and will be releasing the Stooges album, and a review of Fun House by Michael Symons. The ‘Some Pop Primitive’ in the headline for the review refers not to the ‘world’s most frantic band’ but to Melanie . . . go figure (see below at the bottom of this post).

Both her Australian reviews of the live Stooges experience are from Electric Circus gigs (October 23, 1970 and May 14 & 25, 1971). A wider search also revealed an audio recording of a two minute syndicated review of the 1971 shows, ‘Can A Boy Named Iggy Be The Silver Messiah?’ which is just a joy to hear. (radio here)

Sydney Morning Herald (November 1, 1970)

His whole idea is to jolt the audience into a state of fear and shock. When he sings to a girl, or to the audience, he does not do it caressingly but with anger and violence. The girl doesn’t know whether she wants to mother him – or back away. Watching the indecision is part of the sadistic thrill of being in The Stooges audience . . .He seems to embody the violence around in America today.

Sydney Morning Herald (June 6, 1971)

The Stooges are definitely the darlings of the avant garde this year. It must be the spitting.

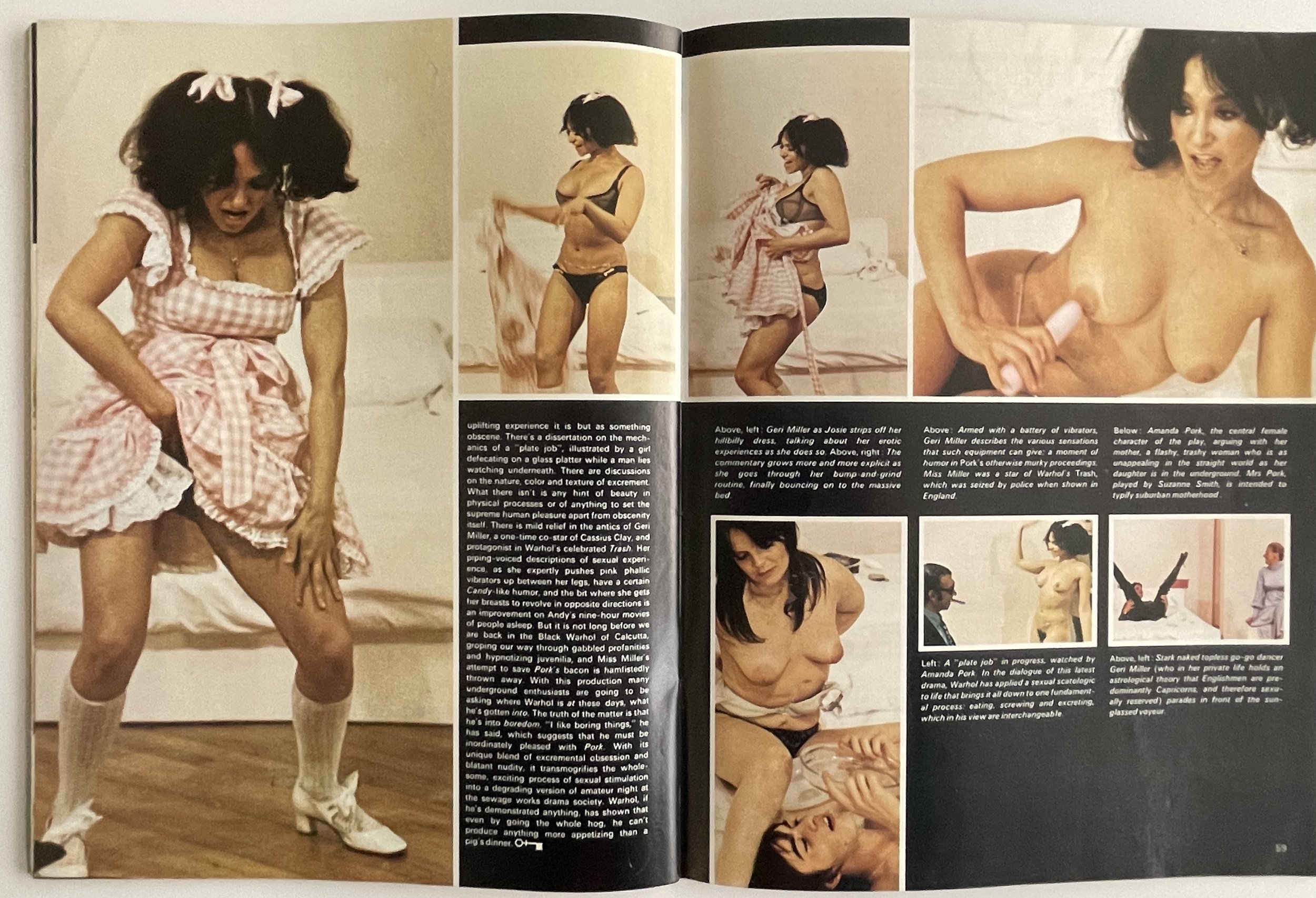

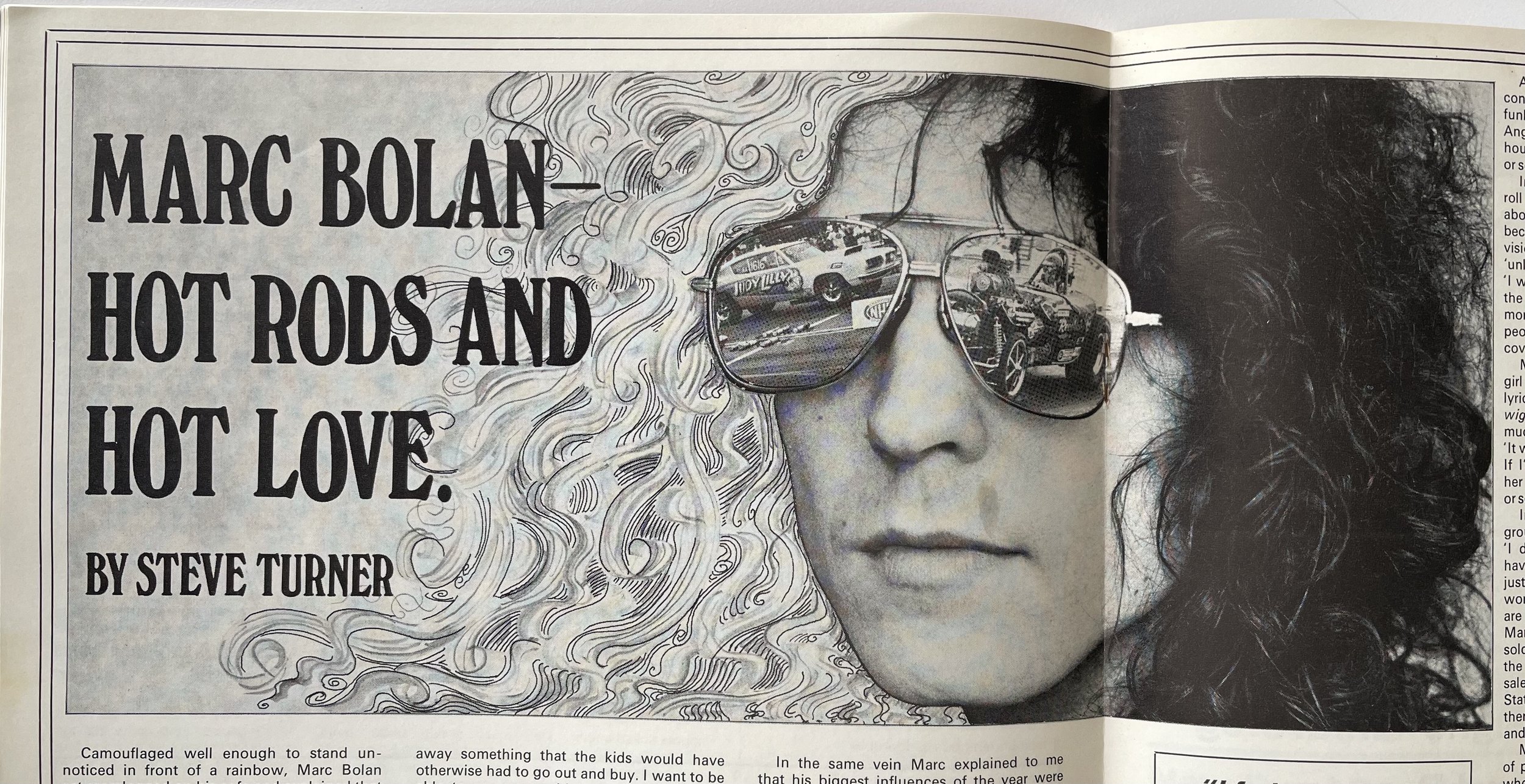

Other than her contract with the Herald, Roxon also penned a weekly column, ‘The Top Of Pop’, for New York’s Sunday News. It’s a great primer to the scene circa 1971–73. Iggy received a fair number of mentions in the sidebar, ‘Amplifications’, along the lines of ‘Iggy Stooge are you serious about making a movie with Andy Warhol?’ (10/71), Iggy of the Stooges joining Lou Reed and the Flamin’ Groovies in London and references to seeing Bowie in Aylesbury with a strong suggestion that she joined other critics that night at the King Sound gig: ‘Detroit’s Iggy Pop wears his hair sprayed silver off stage. . . (with a well worn Marc Bolan T-shirt) . . . glove-tight studded silver pants, eyeliner and black lipstick.’ (July 30, 1972). All echoing the previous week’s column:

Sunday News (July 23, 1972)

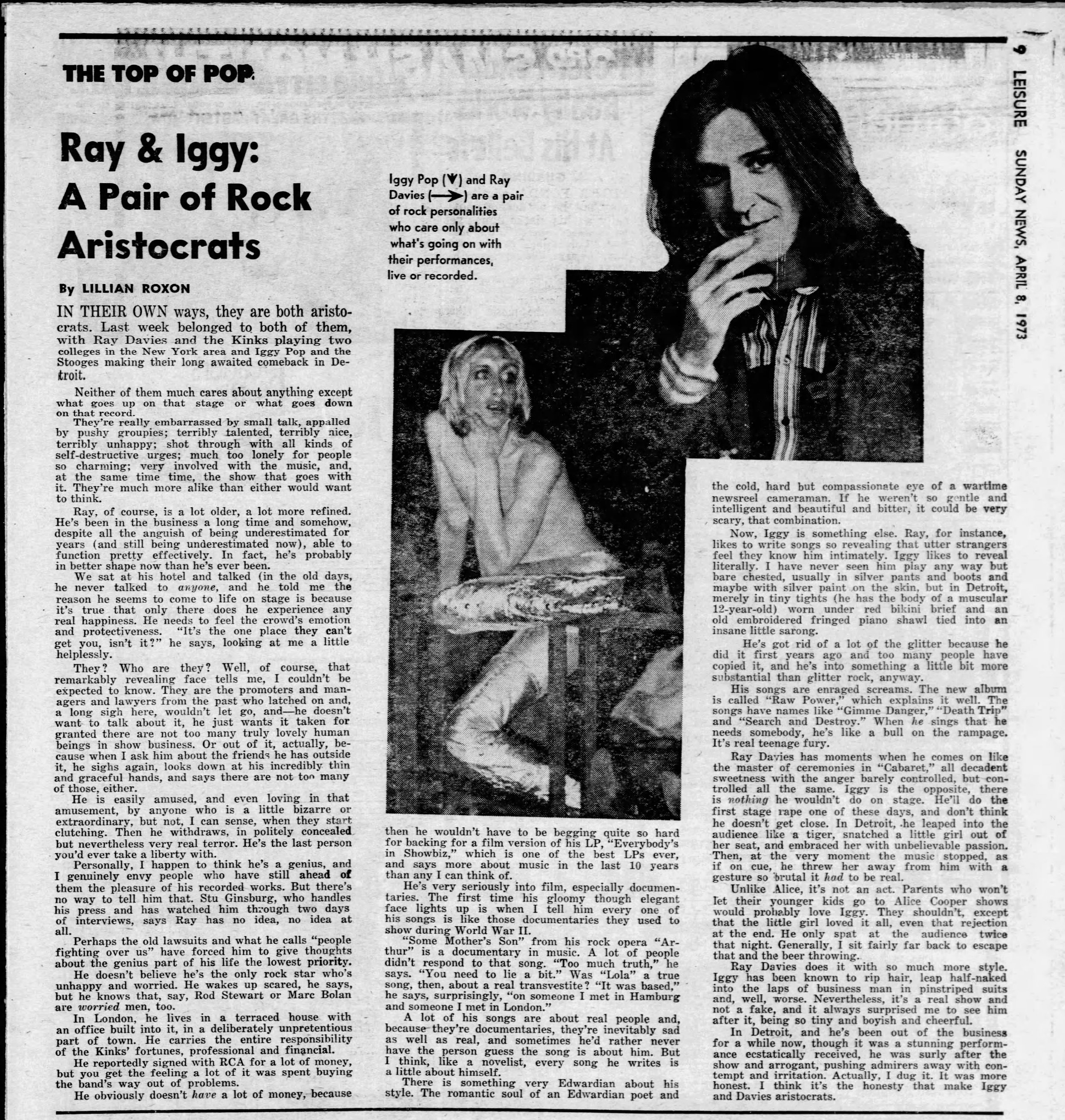

Her first proper review of The Stooges for the Sunday News was of their return, after London, to their home town for a gig at the Ford Auditorium (March 27 1973). Roxon matched her impressions of the Detroit gig with, her longtime favourites, The Kinks in New York. She thought Ray Davis and Iggy were a ‘pair of rock aristocrats’. A strange combination, but they shared an honesty in their art that she appreciated whatever the differences in their performance styles and music.

Sunday News (April 6, 1973)

Gone in Detroit was the glittered torso of the Electric Circus gig, when she last saw Iggy. She wrote, ‘too many people have copied it, and he’s into something a little more substantial than glitter rock, anyway.’ Raw Power is a recent release, a collection of ‘enraged screams’ and on stage, in red bikini briefs beneath ‘an old embroidered and fringed piano shawl tied into an insane little sarong’, Iggy is still, as at the Electric Circus, breaking through the fourth wall, sitting in the lap of audience members, dragging young women on to his podium: ‘there is nothing he wouldn’t do on stage. He’ll do the first stage rape one of these days, and don’t think he doesn’t get close’.

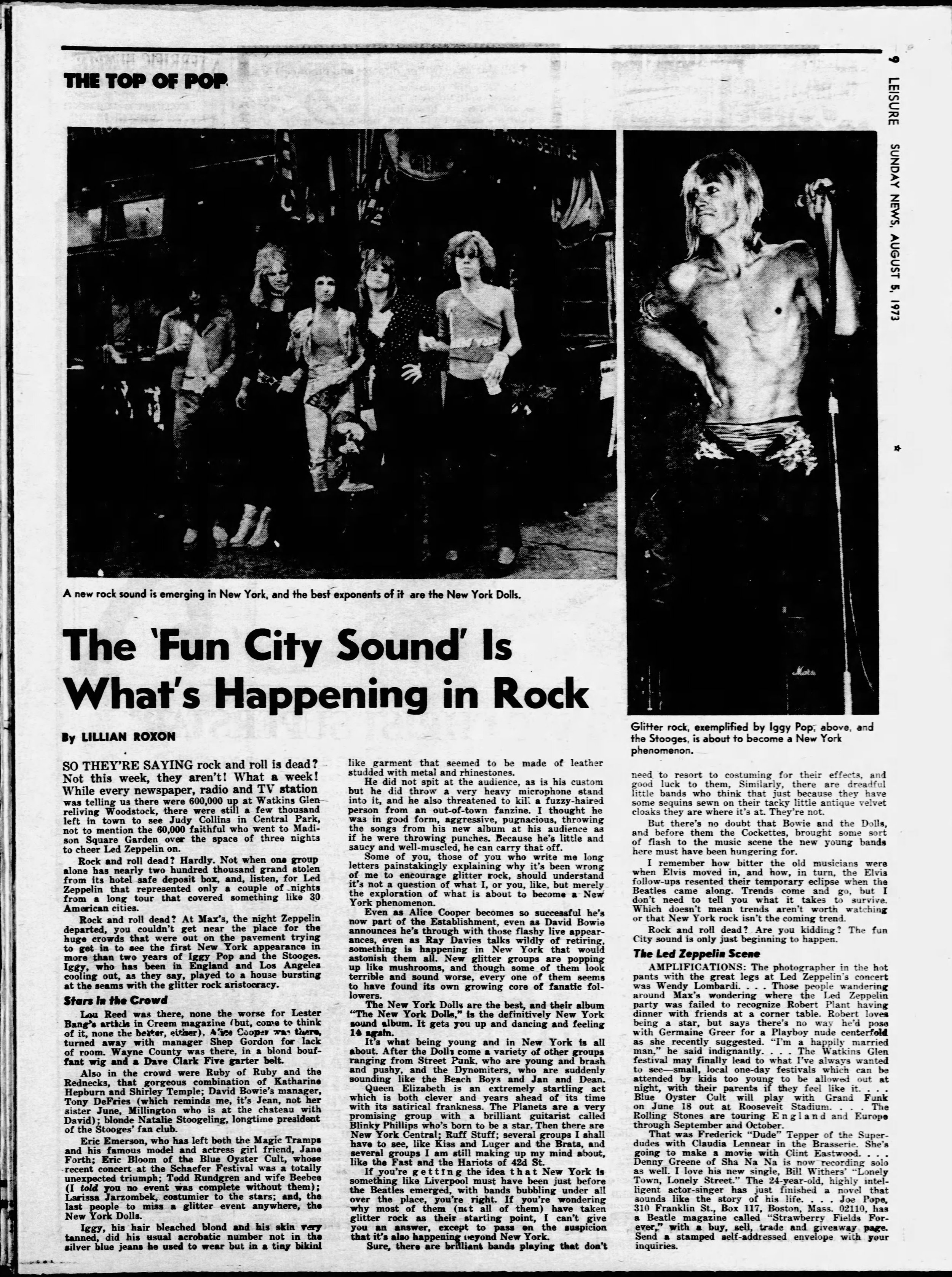

Roxon was an enthusiastic champion of Bowie and Bolan, and helped boost the New York Dolls right from the start. When The Stooges made their return to New York at Max’s Kansas City in July/August ‘73 she covered it along with a review of the first Dolls album

New York Sunday News (August 5, 1973)

A week after that post and three days on from the final Stooges’ gig at Max’s she was dead. Iggy and the Stooges and the New York Dolls her final story.

New York Sunday News (August 11, 1973)

Sydney Morning Herald’s Fun House review

Sydney Morning Herald (December 19, 1970)