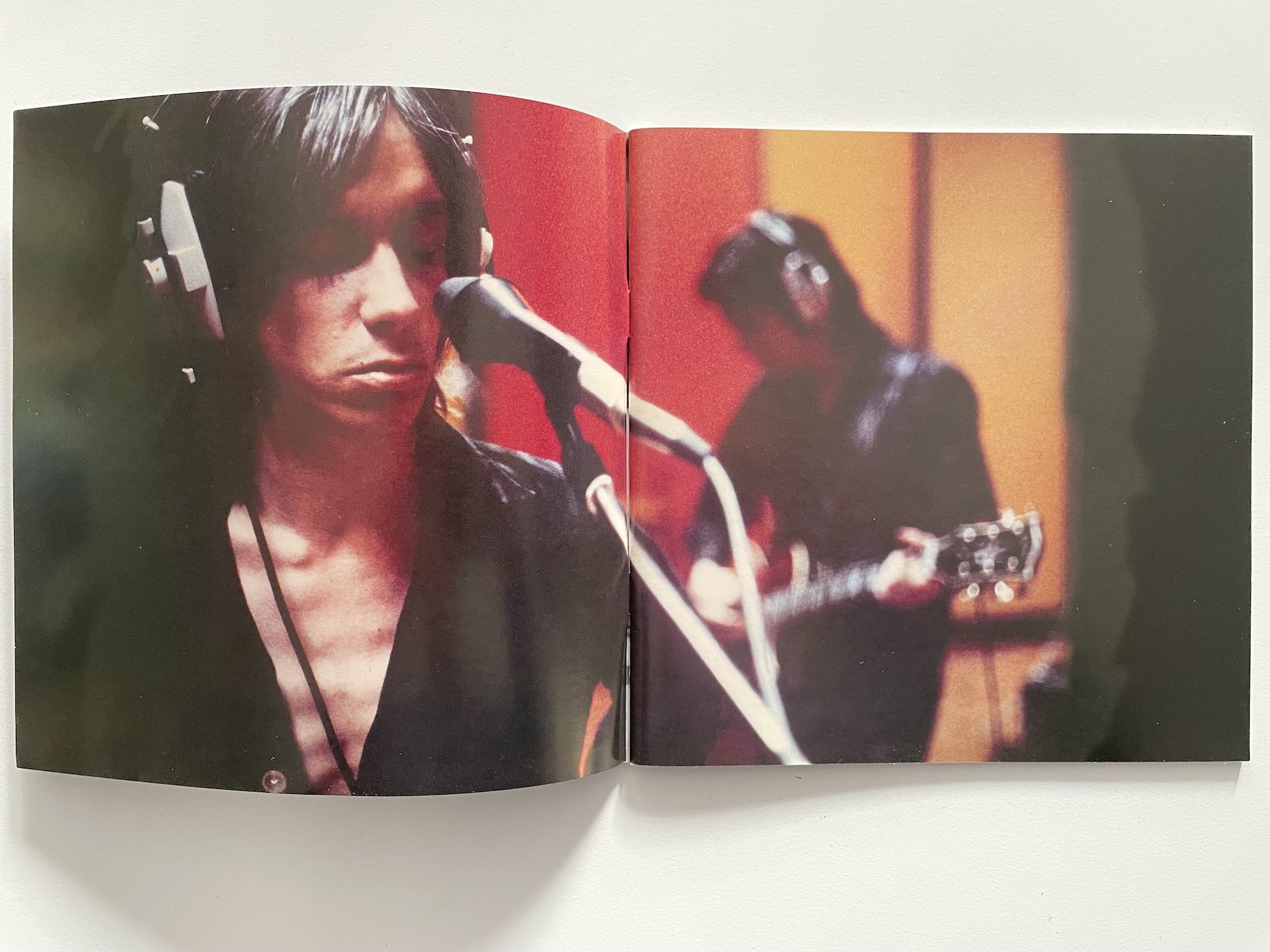

Photo by Bruce Davidson, Brooklyn Gang (1959)

On Friday nights Evie would go with her friend Sue to the ice rink, it was the place to see other teenage girls and talk about boys. In an elaborate ritual, she curled her straight hair and held it in place with clouds of hairspray. The fix rarely lasted the first part of the evening. Evie’s ritual eventually abandoned when Aces showed up at school. Aces shunned Julie, the most popular girl, and hung out with Evie. She now lets her hair stay straight, Aces preferred it that way.

His given name was Rhett, but he had had a tattoo of aces done while in Liverpool touring Britain with his father, an actor, so Aces was what he was now called. Before Evie met him he’d been expelled from his previous schools, at Le Conte he stayed away from the in-crowd, he followed his own path and took Evie on a date in a stolen car

Photo by Bruce Davidson, Brooklyn Gang (1959)

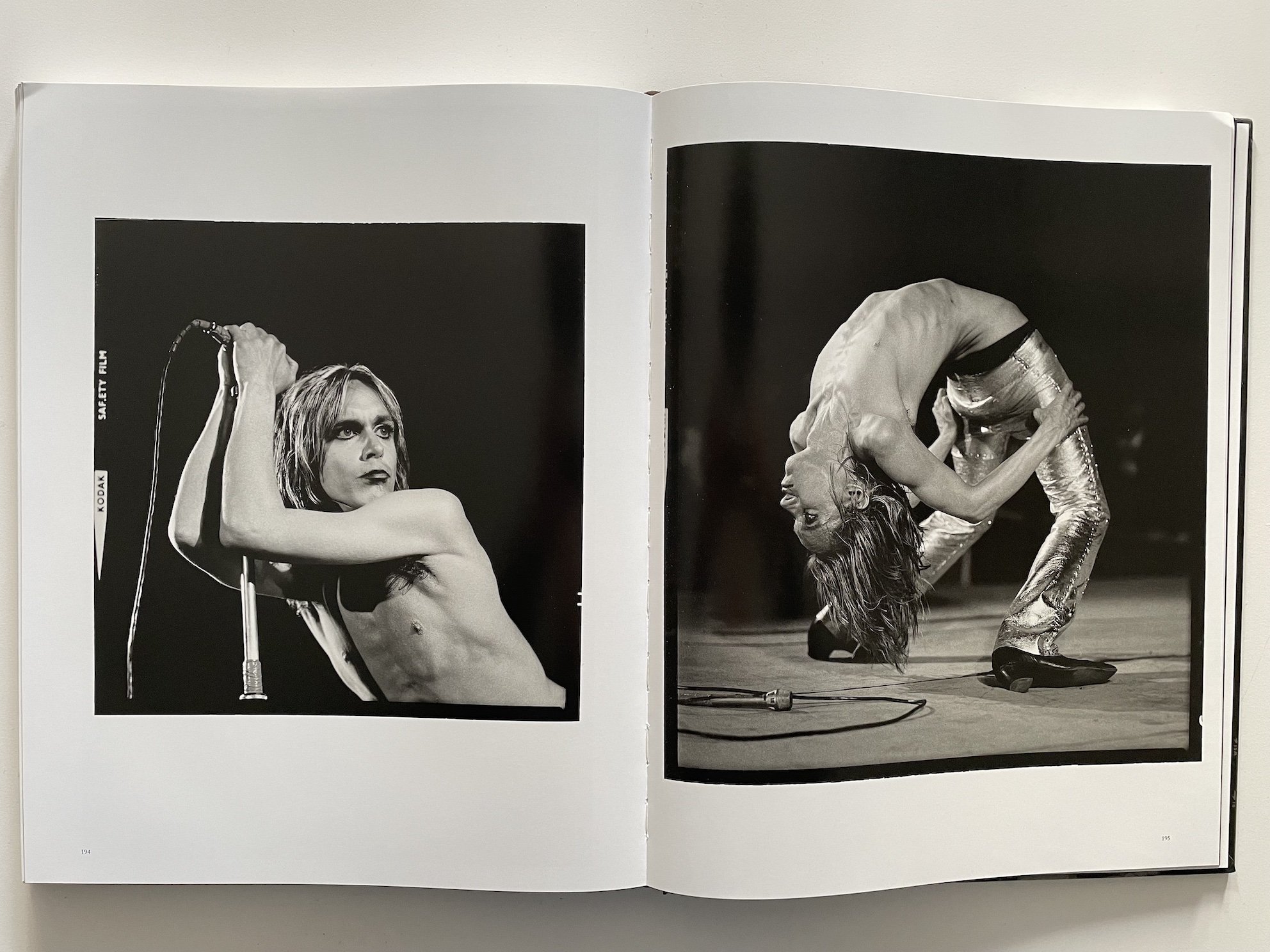

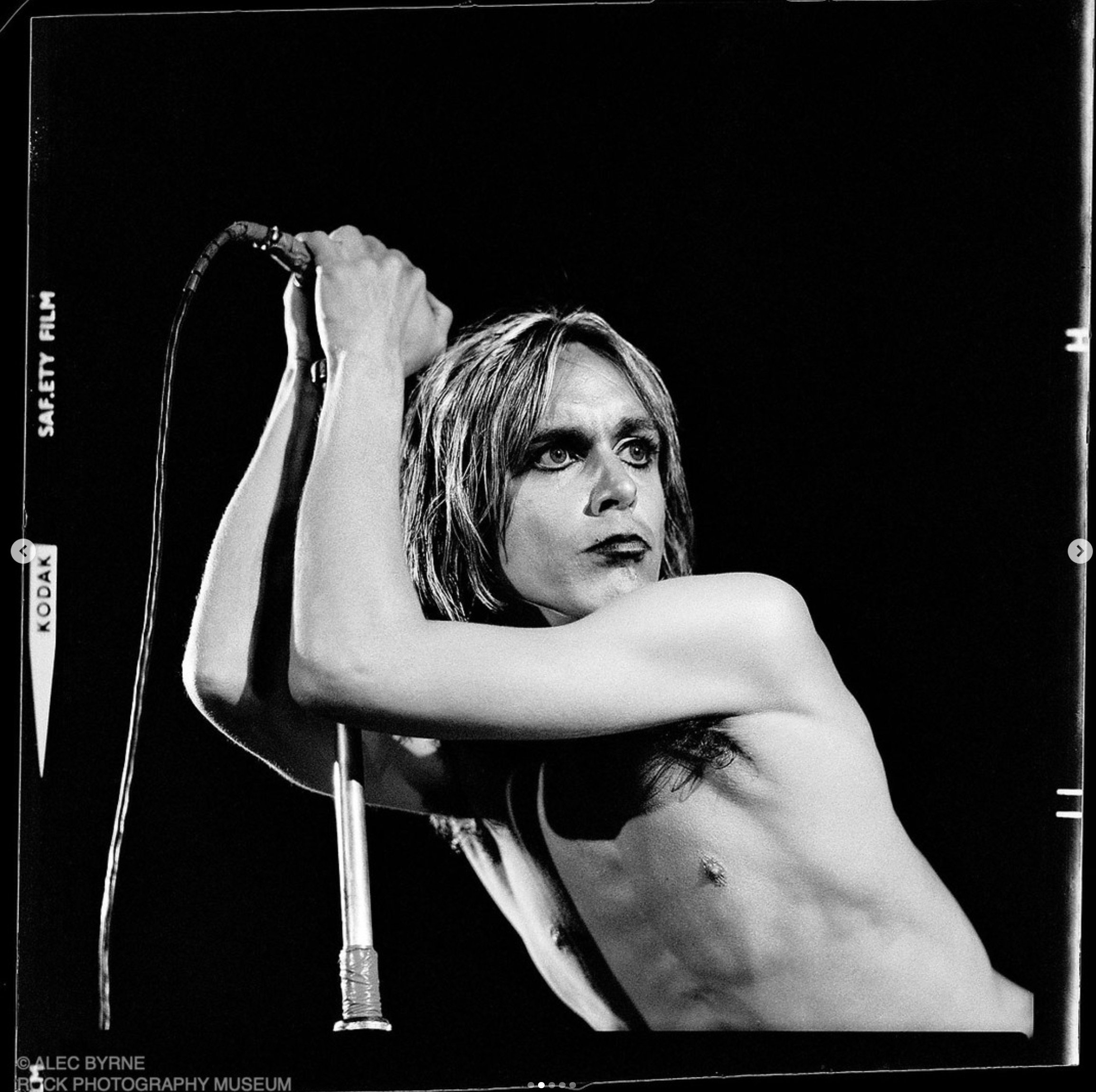

It wasn't just the way his yellow eyes stripped the plaster off the walls that threw the school open for grabs. And it wasn't his black hair that fell to his chin in the front in criminal defiance. It was that the girls went along with him at once, all the whole school did.

Who could resist the way he threw back his head and slapped his thigh in unheard-of abandon, in our starved colony? He dressed in black, black motorcycle jacket, black shirts, black Levi’s and black boots with his black eyelashes framing his acetylene eyes that flickered out in pure hate at the concepts of anything being "for your own good" or anyone "who knew best”.

His report card noted his high IQ but also his ‘poor attitude’. Eve and Aces’ chaste love affair ended after the ride in the stolen car, and then he vanished. A little while later Eve learnt from Aces’ only friend, Louie, that he had been busted. ‘Grand Theft Auto?’ she asked. ‘No’, replied Louie, ‘Grand Theft Yacht’. He’d stolen the boat in Balboa and was heading for Tahiti when the coast guard stopped him.

Evie learns that ‘power was the quality of knowing what you liked’ and she now knew she’d much rather head for Tahiti than go to the school dance.

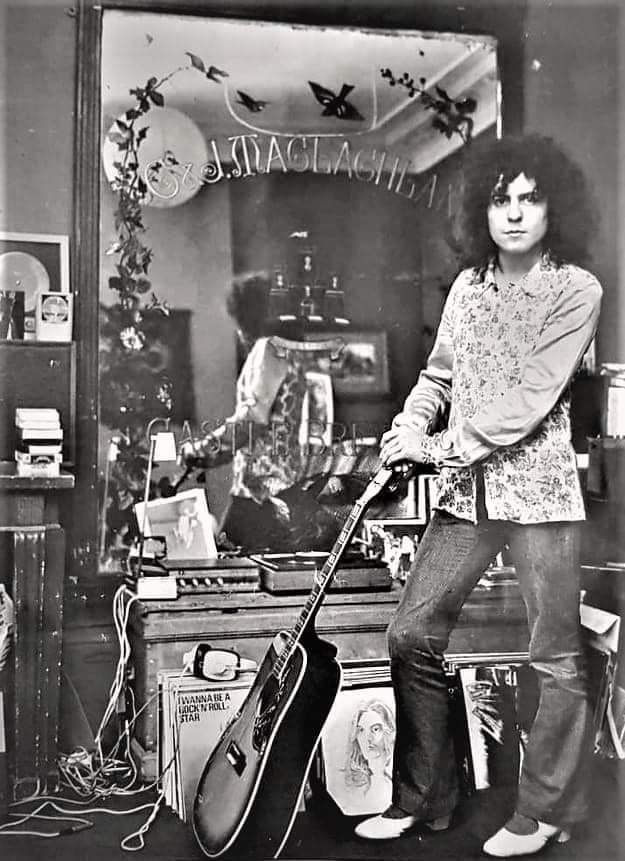

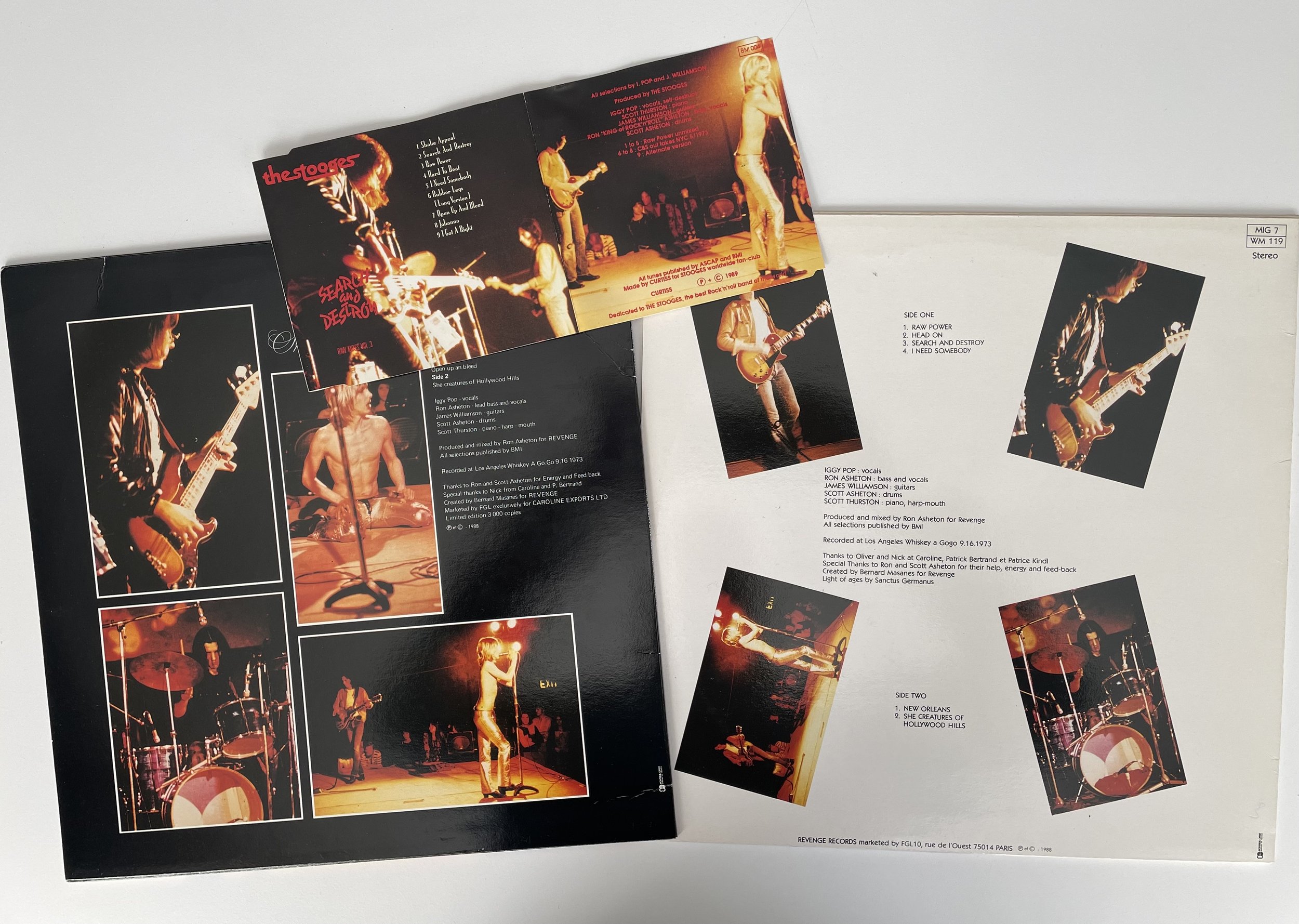

Eve’s Hollywood by Eve Babitz, from which this story is taken, was published in 1972. That year and in the next few years to follow American music, like its British counterpart, was obsessed with the 1950s and early 1960s, especially with the girl groups, The Ronettes, The Shangri-las, The Crystals. Their sound was echoed and refracted by the New York Dolls for sure, but it was even more present in Bette Midler’s debut, with its cover versions of ‘The Leader of the Pack’ and The Dixie Cups’ ‘Chapel of Love’. The album opens with the invitation Bobby Freeman made in 1958, ‘Do You Wanna Dance’? This was not pastiche but a tribute to her roots, Greil Marcus wrote. Laura Nyro’s Gonna Take A Miracle, backed by Labelle, was also a heartfelt homage, it included ‘the great R&B hits that Laura once wailed where the echo was best: in a New York subway station’, ran the tag-line in the record company’s advertisement for the album. She covered the songs she felt Smokey Robinson, Phil Spector, Curtis Mayfield and Marvin Gaye had written especially for her.

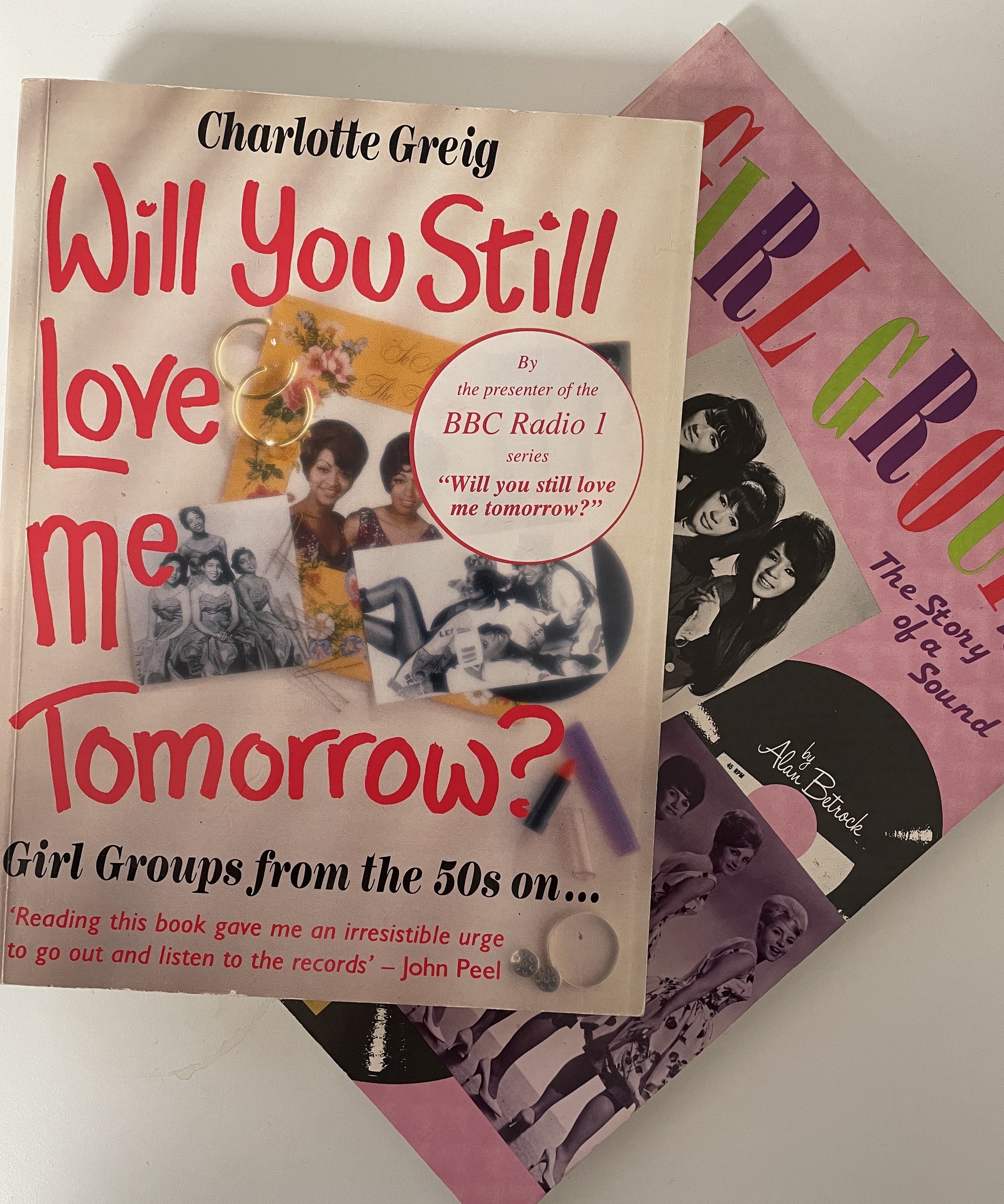

In Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow: Girl Groups from the 50s on . . . Charlotte Greig wrote about how those ephemeral, disposable, records produced by Shadow Morton, Leiber and Stoller and Phil Spector worked their magic on an audience of teenage girls and just why someone, like Nyro, might think those songs spoke directly to her and about her experiences. It is a brilliant book, one of the best written on pop music.

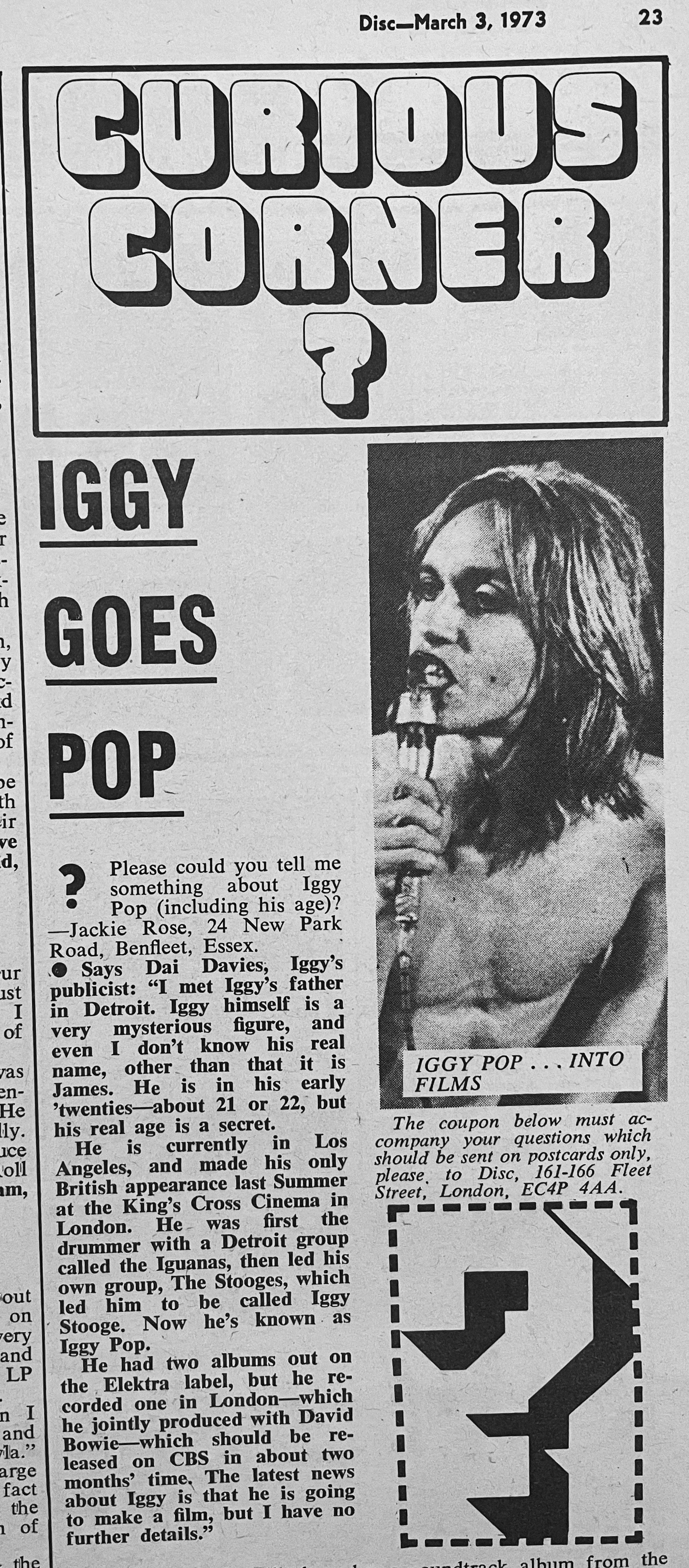

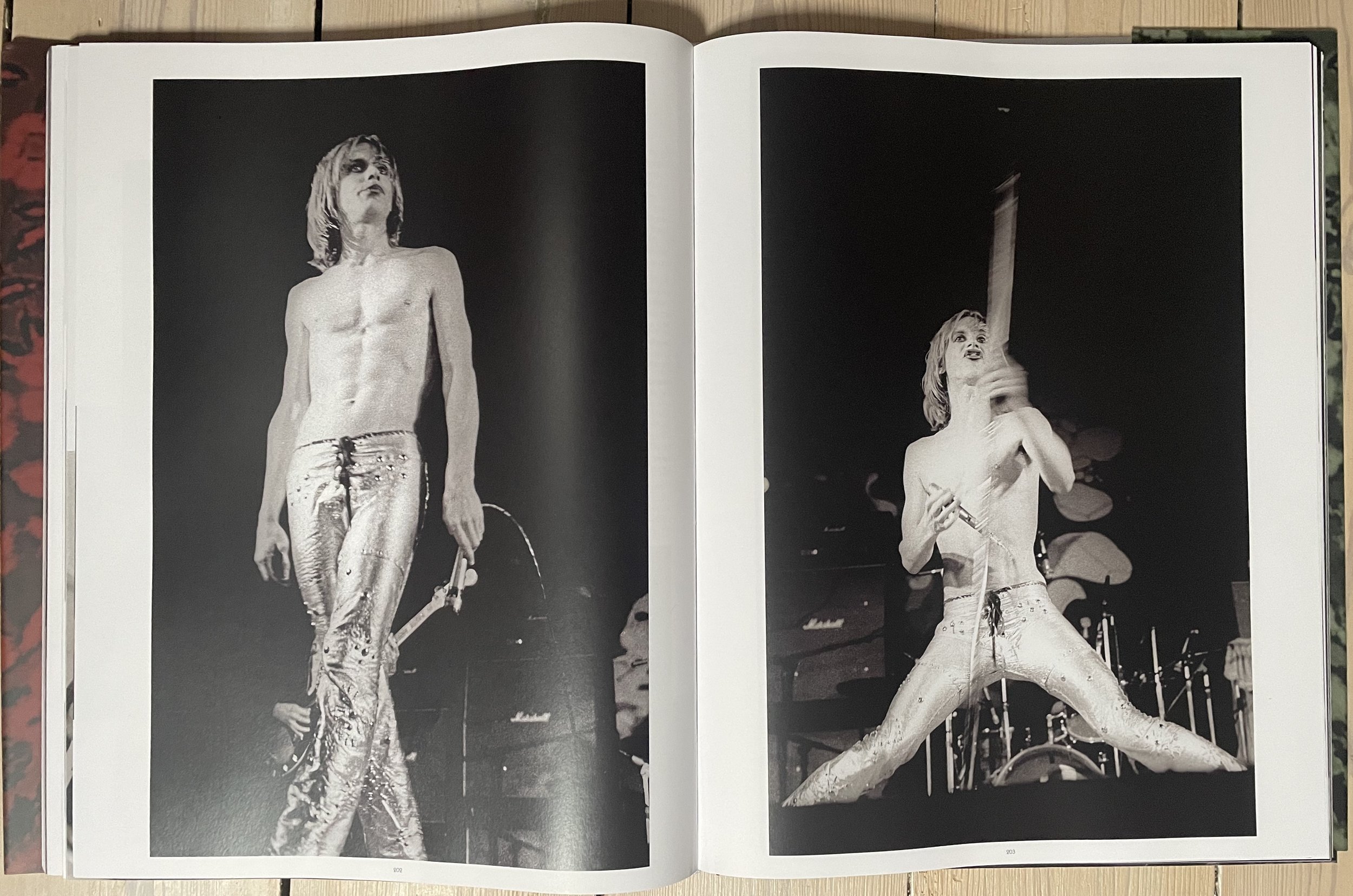

If young women like Babitz, Midler and Nyro were looking back at the figure of the bad boy, who features in these songs and in their teen dreams, others looked to exploit that nostalgia. Before punk was ‘punk’ it was a bad boy with a DA and an attitude

‘OK Punks . . .’ Sha Na Na and Brownsville Station set the pace for the Ramones and the rest of the New York mid-seventies scene . . .

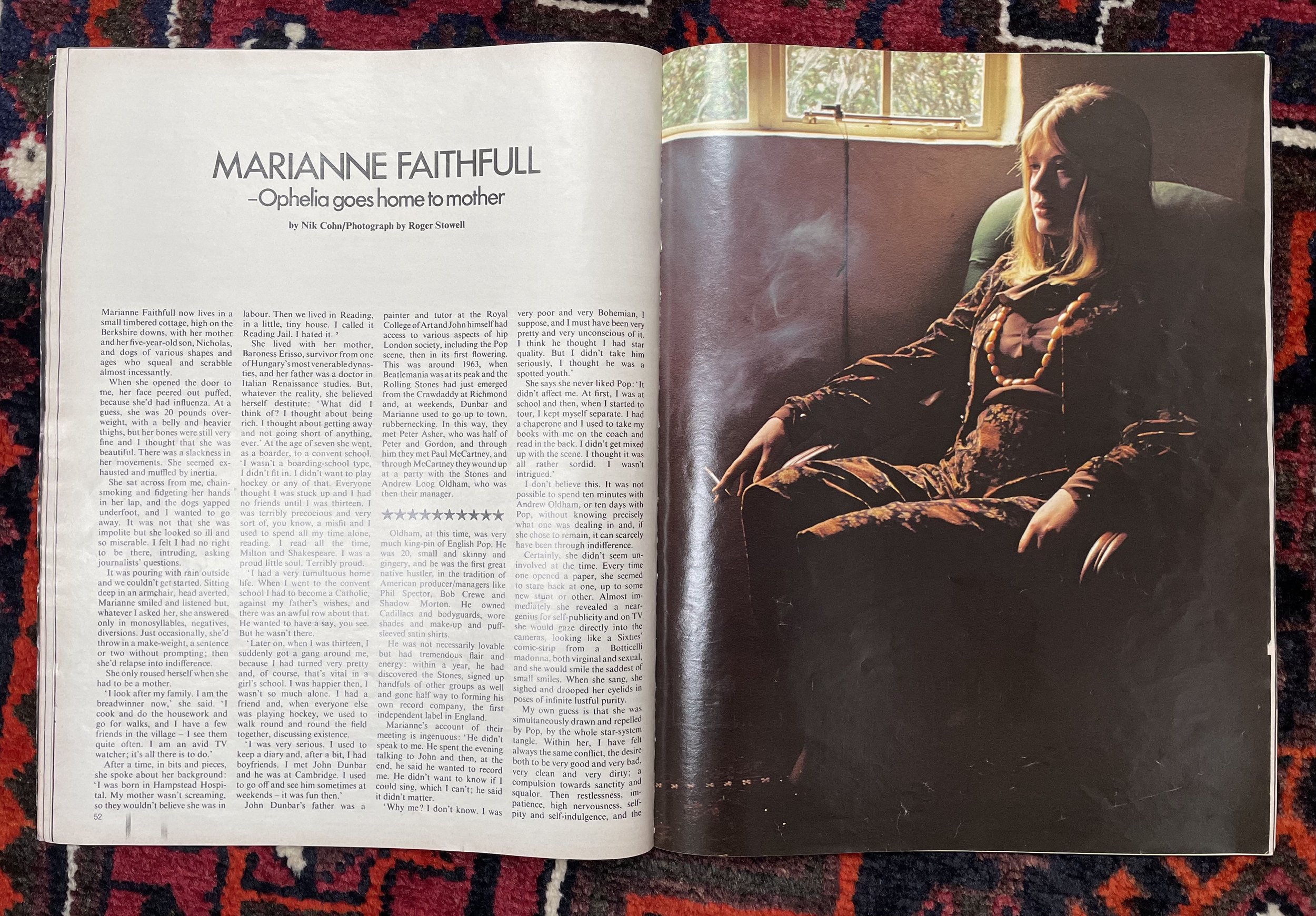

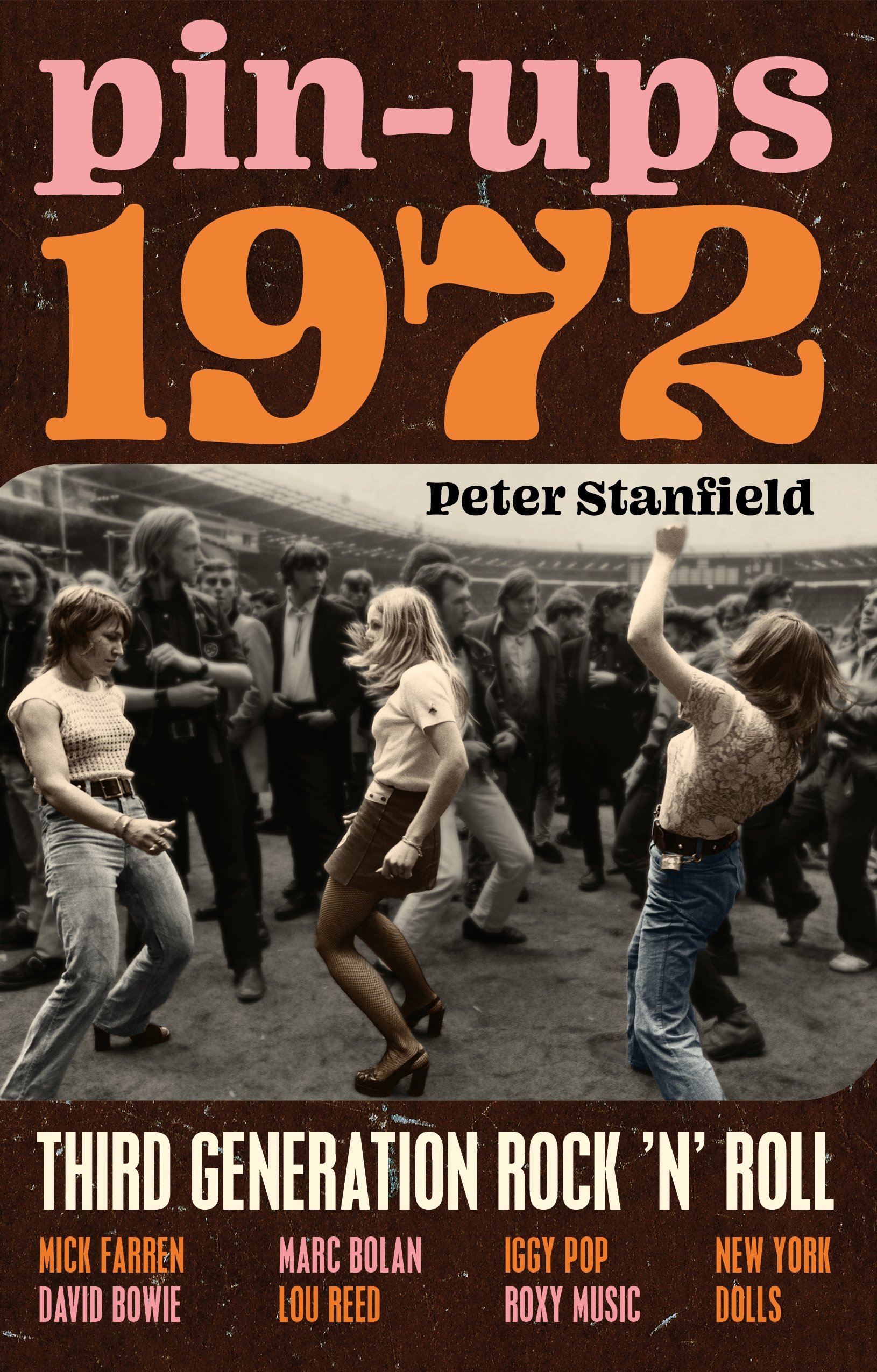

All this and so much much more is in Pin-Ups 1972: Third Generation Rock ‘n’ Roll and, yes, Nik Cohn too