Johnny O’Clock – what’s in a name?

Johnny O’Clock is a gambler who doesn’t gamble; a man who tries to stay above the low-life he has to mix with, a patriarch without a family, and a lover without a faithful partner. In a world without honour he tries to be a just man. He is also something of the dandy. As for the film he gave his name to, it was part of the cycle of post-Depression era crime movies featuring punk hoodlums that all had the name ‘Johnny’ in the title. A partial list: Johnny Apollo (1940), Johnny Eager (1941), Johnny Holiday (1941), Johnny Come Lately (1943), Johnny Angel (1945), Johnny Allegro (1949), Johnny Stool Pigeon (1949), Johnny One-Eye (1950), Johnny Dark (1954), Johnny Gunman (1957), Johnny Rocco (1958) and Johnny Cool (1963). As always, the Western got in on the action with Johnny Guitar (1954) and Johnny Concho (1956), but they were just sideshows to the main event.

The cycle followed a long lull in the production of gangster films, a result of the moral backlash to movies such as City Streets, Public Enemy, Quick Millions, and Little Caesar (all 1931). With the wartime and postwar relaxation of its regimen of self-censorship, Hollywood again exploited the figure of the hoodlum. This time out, however, the gangster’s ethnicity was less readily identifiable as Italian in origin. As a name, Johnny may not, as with Caesar Enrico Bandello (Little Caesar) and Tony Camonte (Scarface, 1932), been specifically Mediterranean in origin, but it could still carry the taint of the inner-city; suggesting a character raised in the tenements, educated on the streets and, depending on the name it was coupled with, still hold ethnic connotations. As the diminutive of John, ‘Johnny’ was also juvenile, and it was certainly déclassé – entirely lacking in middle-class respectability.

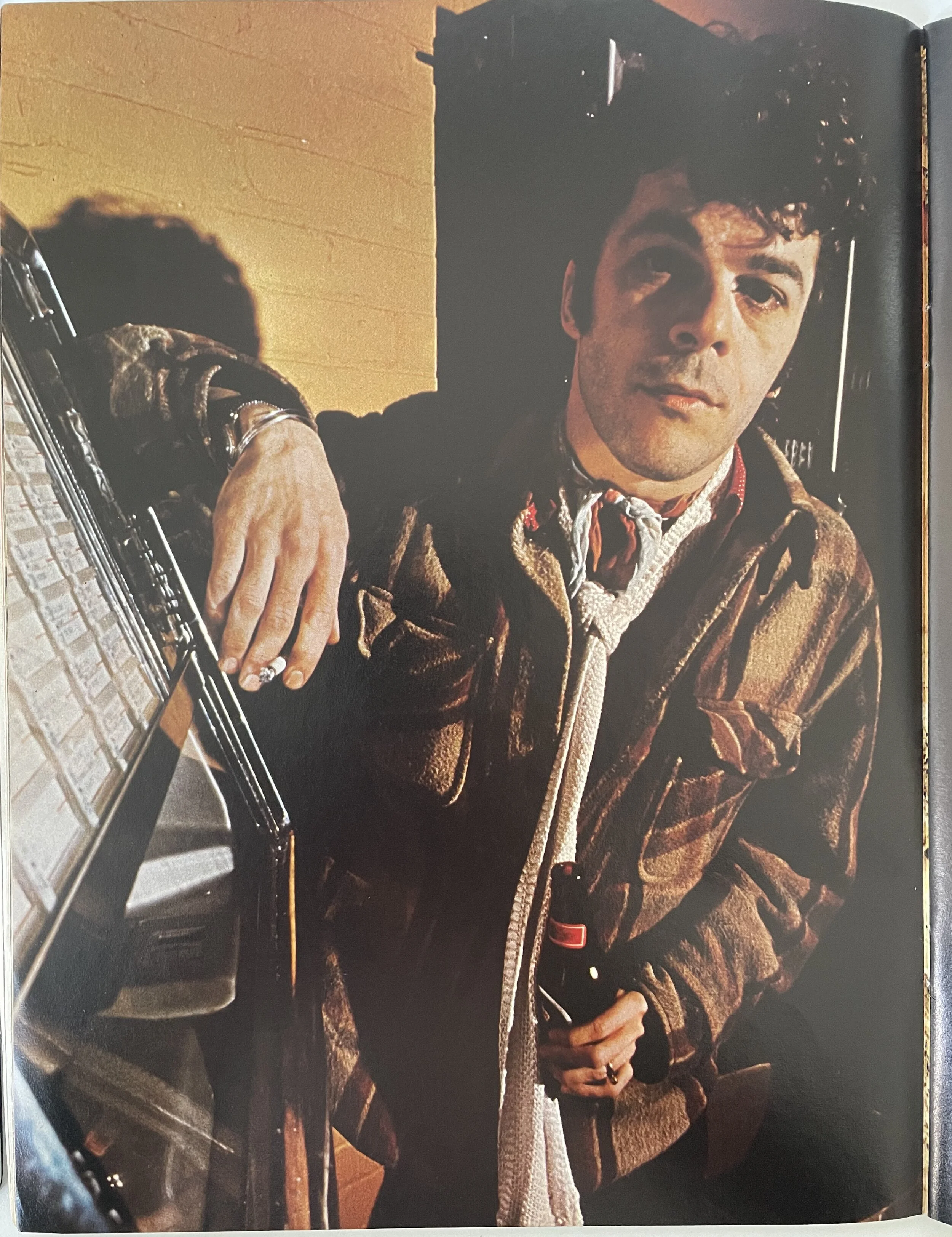

In 1944, Dick Powell was looking for a little bit of that taint of the low to help revitalize his career. He had just turned 40 and the role, as a juvenile romantic lead, that he had once taken in films such as 42nd Street and Footlight Parade (both 1933), was no longer an option. Like Humphrey Bogart a little before him, he reinvented himself as a tough guy, beginning with the Raymond Chandler adaptation Murder My Sweet (1944) and followed by the equally hard-boiled Cornered (1945). The two films had been produced and directed by Adrian Scott and Edward Dymtryk respectively, both would be caught up in the Communist witch-hunts of the McCarthy-era. The third in Powell’s run of tough guy films, Johnny O’Clock was directed and written by Robert Rossen, like Scott and Dymtryk also a one-time member of the American Communist Party. Filmmakers such as these brought to Hollywood a tougher, more authentic view of crime and the city; one that was formed by a direct experience of Jewish American ghetto life. The class politics of Rossen’s film may not be as pronounced as it is in his Body and Soul (1947) or in Abraham Polansky’s Force of Evil (1948), but it’s still right there on the surface, if you care to look.

‘“Johnny O’Clock”, that’s a funny kind of name’ the hotel desk clerk tells J. Lee Cobb’s policeman, Koch. The straight life isn’t for Johnny, he doesn’t get up until nine, PM that is. When more respectable folk are starting to think about going to bed, Johnny’s day is only beginning. His daily routine is an inversion of the good citizen’s and his domestic life is equally strange . . . He’s woken by Charlie, a younger, more obviously, proletarian man, who moves around Johnny’s apartment with an intimate’s familiarity. Over breakfast, Johnny gives him a shirt, in return Charlie gives Johnny a watch engraved with ‘To my darling with unending love’. Before there is time to do a double-take on this queer set up, Charlie explains the gift is from a dame. The relationship between the two men, nevertheless, remains entirely unsettled.

In the hotel lobby, Johnny passes a lecherous eye over a woman, caught in the act by Koch, he tells the policeman it is a habit; giving himself an alibi for a crime unspecified. Crime and sexual deviancy, in the parlance of the day, had long been figured as synonymous in Hollywood’s films, think Tony Camonte’s incestuous desire for his sister in Scarface or Rico’s unspoken love for Joe Massara (Douglas Fairbanks Jr.) in Little Caesar. There are no shortage of women in Johnny’s world, most who make clear their availability, he can even play a convincing paternal role with Harriet (Nina Foch), though Koch misreads his intentions toward her. His one-time lover, Nellie (Ellen Drew), and now wife of his partner in crime, Guido Marchetti (Thomas Gomez), still wants Johnny; she gave him the engraved watch. But it’s with Harriet’s sister, Nancy (Evelyn Keyes), that the romance is played out (or begins to unravel). Nancy is smitten by Johnny from the moment they meet. Inevitably, she is curious about Charlie. ‘He’s my man’ Johnny says. ‘You say that like you’re used to it’, she replies. ‘He’s a guy who just got out of the jug, I give him a place to live. He’d cut off his right arm for me, right up to the elbow’, says Johnny, making the relationship between the two men even less comprehensible to her.

Johnny’s world is covered in a shroud of deception and dissembling. ‘What’s it all mean?’, asks Nancy admiring the Jose Clemente Orozco painting hanging in Johnny’s apartment. He tells her it can mean whatever you want it to mean, and then he tells her it is a reproduction and the fireplace it sits above is also fake and that things, anyway, look better with the lights off. She agrees with him, nothing is to be trusted , and yet she still wants Johnny to say sweet and pretty things and let her pretend they are true. He kisses her but she pulls away and they then throw words at each other. The scene fades on a kiss and returns with Johnny having changed out of his Prince of Wales check suit into evening attire. What happened in that fade between the costume changes? Did they make love? The look they give each other could be post-coital or it could be so much more innocent. ‘You look nice’, she tells him. ‘A showcase for the suckers’, he says. ‘Let’s make the words mean what they say’, she says.