Third Generation Rock ‘n’ Roll

That headline is not a phrase you hear much of – or in fact at all – these days, but in 1972 it was a much-discussed concept that attempted to define the music and performance of the early 70s as demonstrated by the likes of David Bowie, Alice Cooper, Roxy Music, New York Dolls and T-Rex. As author Peter Stanfield explains in his fabulous new book Pin-Ups 1972 about the London music scene in 1972, this went by other names too – Fag Rock and Poof Rock being just two of them – which is a reminder of how insensitive even the progressive rock papers of the time could be.

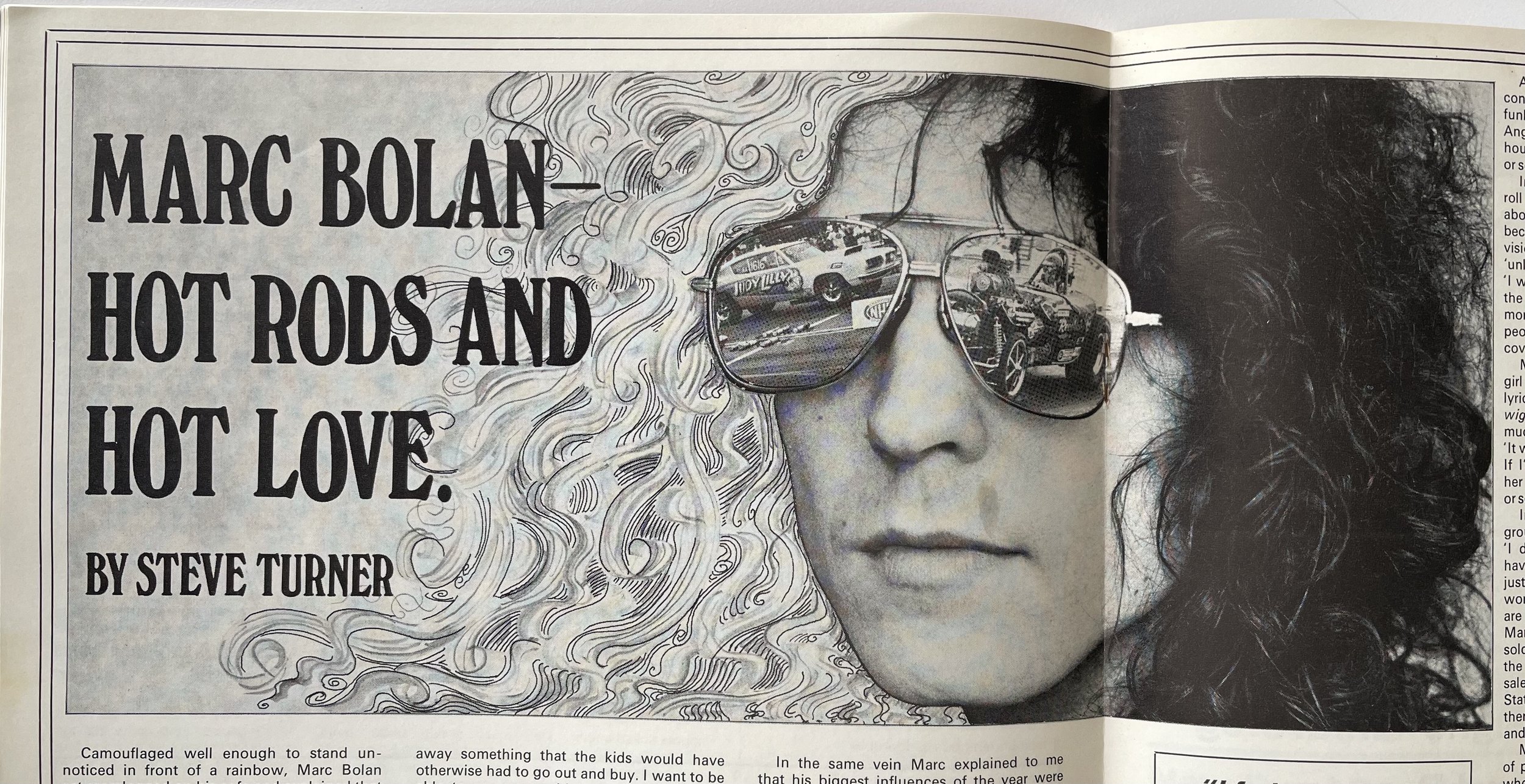

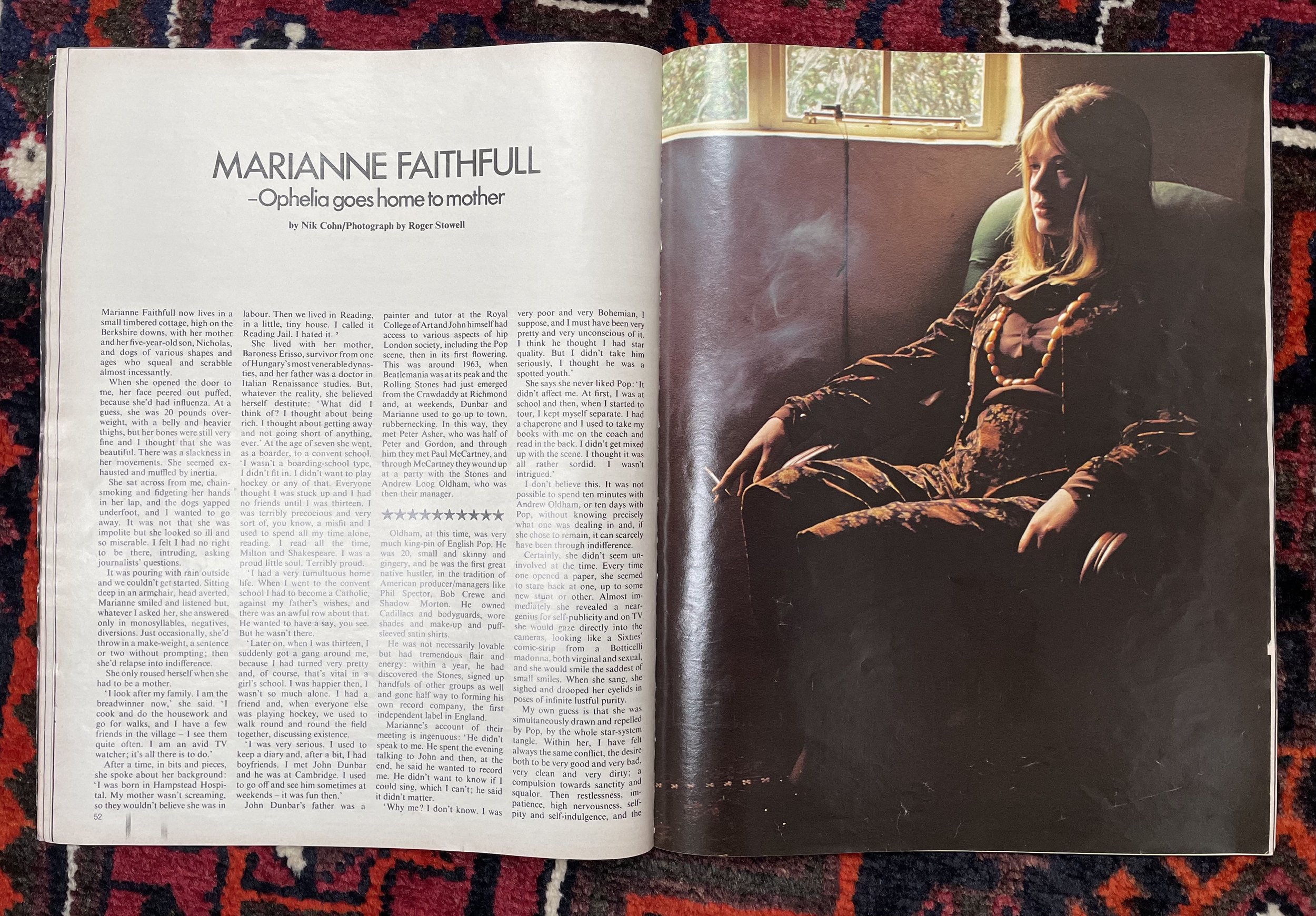

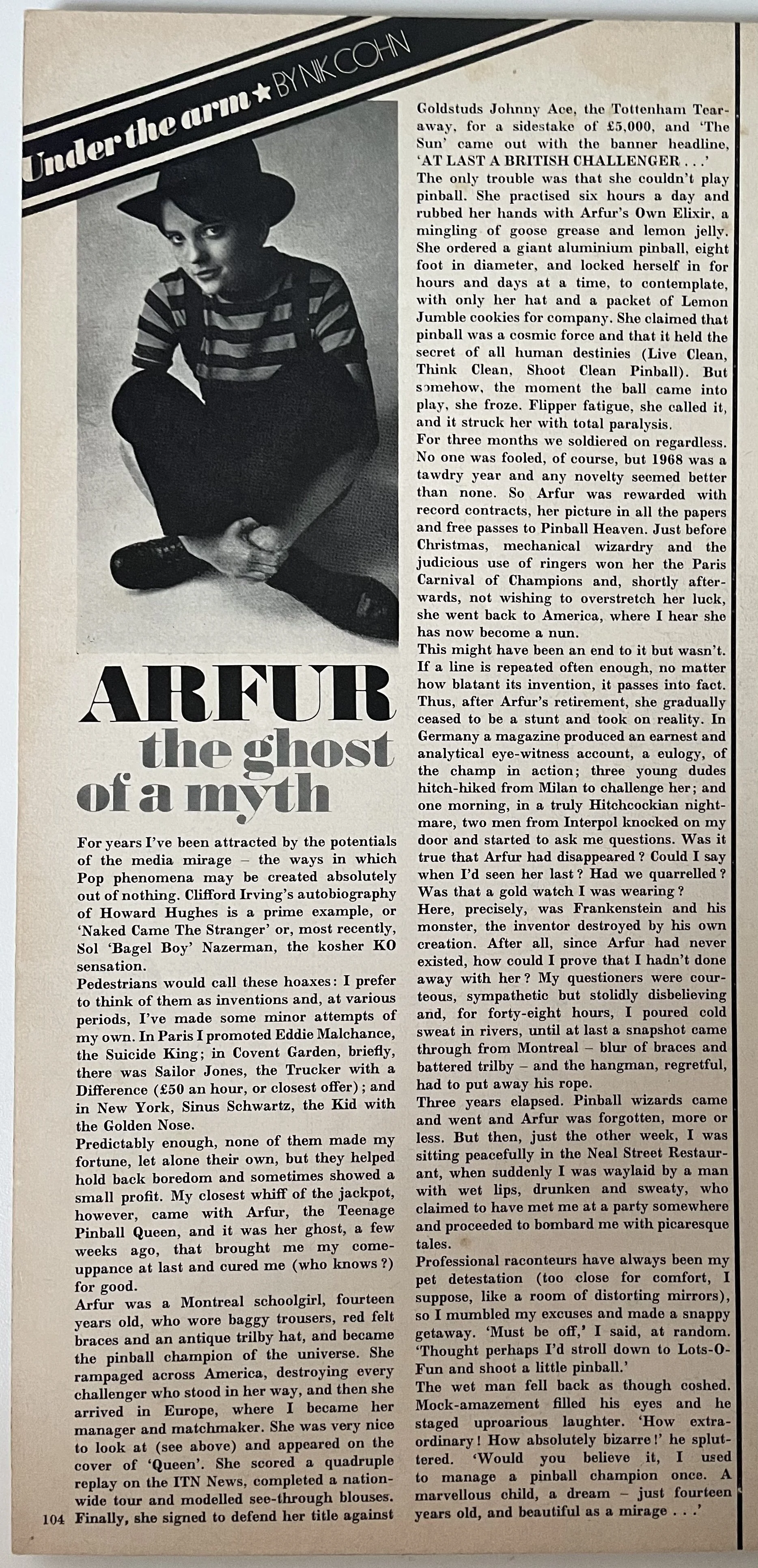

That distance between then and now is the focus of Stanfield’s book. So much has been said and written about the 1970s that it’s easy to believe we all lived through them and already understand everything there is to know, but by going back to the journalism of the time, Stanfield demonstrates how writers were attempting to comprehend the music of the time without benefit of hindsight or obscured by four decades of received wisdom. Stanfield has devoured the journalism of 1972 – underground, national press, music weeklies, colour monthlies, even soft porn titles – to examine the music through a detailed reading of the writing of Nick Kent, Nik Cohn, Richard Williams, Michael Watts, Simon Frith, Mick Farren, Chrissie Hynde and many more – not just their greatest hits, but deep cuts that even they will have forgotten writing.

We see these writers in real time try to get to grips with the ambiguities and contradictions of third generation rock and Stanfield writes in an approximation of these pioneers, dropping theories, connections and cultural references with intoxicating verve, daring the reader to keep up and learn something. Look it up or go with the flow, your call.

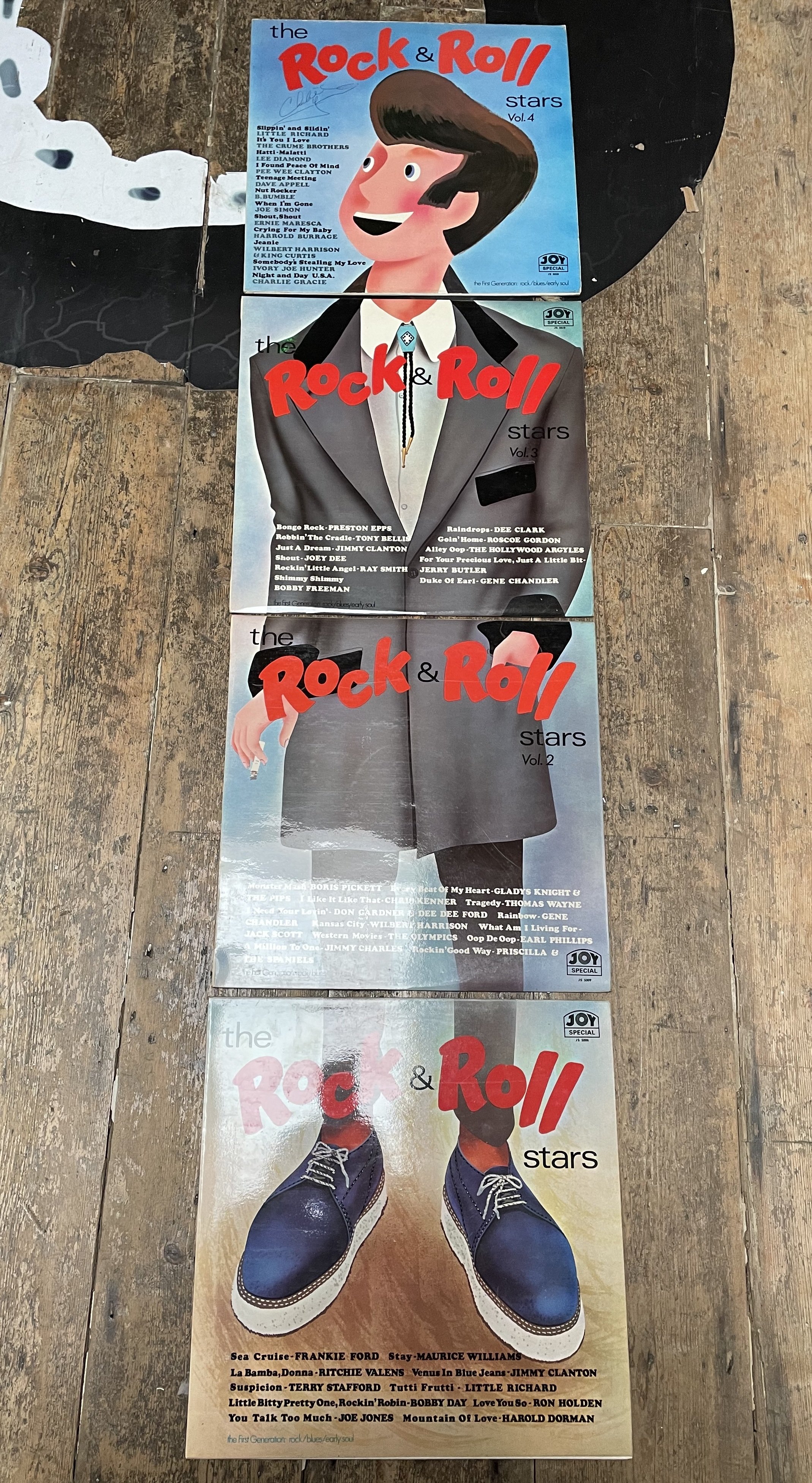

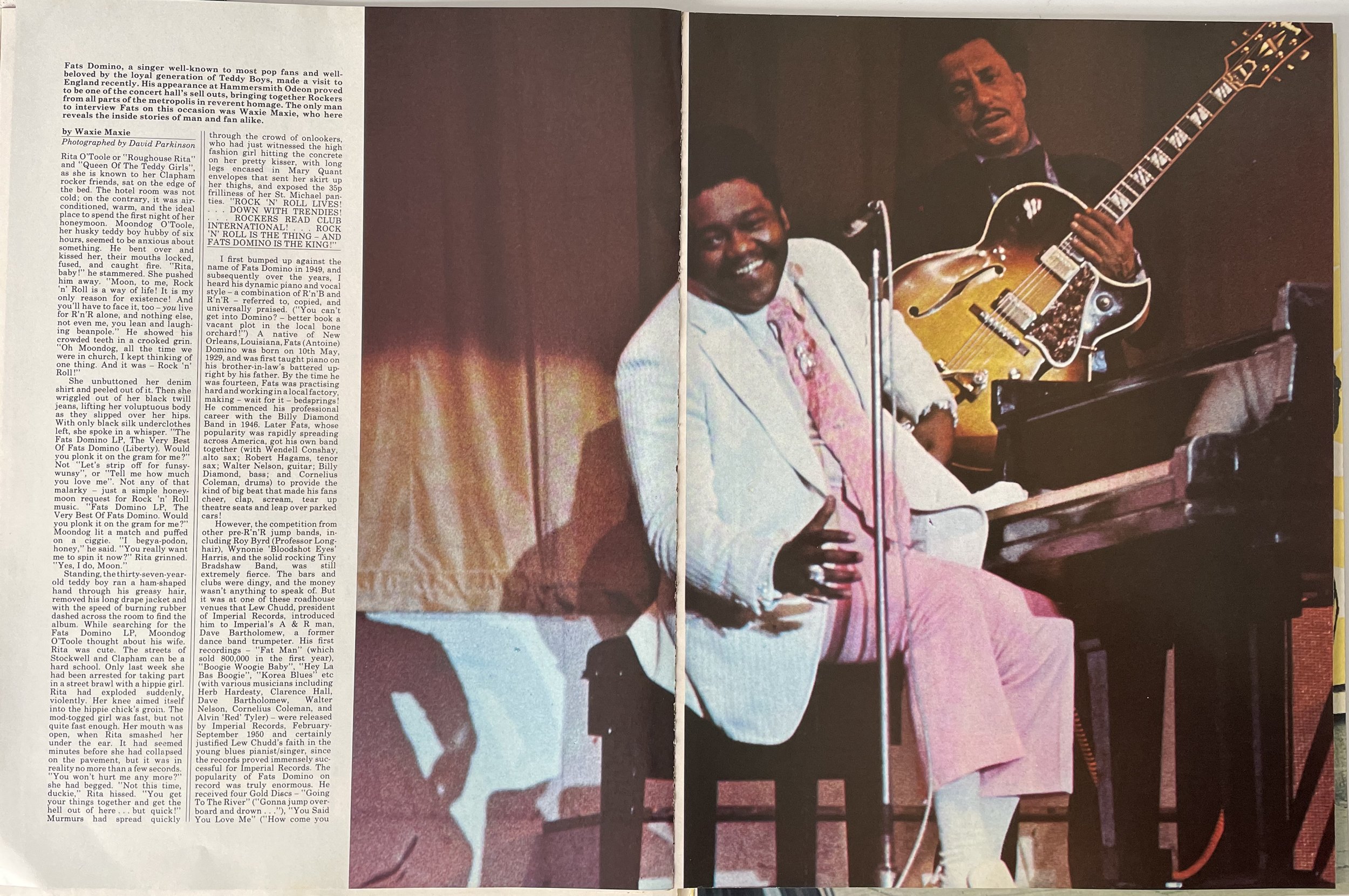

What is third generation rock? By this reading, the first generation were the original ’56 rockers – Elvis, Chuck Berry, Little Richard – and the second generation were those that grew from R&B – the Beatles, Stones, Who, Kinks, Floyd, Zeppelin and you know the rest. Third generation were those that followed, essentially the ones who had more time to understand the grammar, scriptures, cliches and language of rock and roll and then tried to do something different with it – even if many of them, Bowie, Bolan, Lou Reed, Iggy Pop for starters, had been making music for almost as long as the second generation.

It’s a slippery concept (whither Hawkwind and the Pink Fairies?), as such genre-defining often is, but that isn’t really the point. What compels is the approach of exploring the acts through the media of the time. We see hippie journalists struggle to accept the sudden elevation of Marc Bolan from underground hero to teenage fantasy, haphazardly chronicle the New York Dolls’ ill-fated trip to London in 72, or write in awe of the arrival of the semi-mythical Iggy Pop and Lou Reed when the pair come and live in London (Lou Reed settling down in Wimbledon of all places). How do you make sense of Bowie and Roxy Music, when they are happening right in front of your eyes and you have no real frame of reference? The latter explains why for much of their first year, Roxy are likened to Sha Na Na: when something genuinely revolutionary happens, critics are left grasping for comparisons – only later are they able to go back and make it all fit together. But watching that struggle, and the sheer intellectual effort demonstrated by so many writers of the time, is fascinating and a little humbling. The through-line to punk and indie is clear to us but obviously was unknown at the time, and despite walk-on roles for Malcolm McLaren and Glen Matlock, Stanfield wisely leaves that largely unsaid, helping to seal 1972 into its own time capsule.

That makes this very much a book for those who enjoy historiography and media studies almost as much as they love rock and roll. What you don’t get is recycled anecdotes, biography or even too much in the way of music criticism – although the reappraisal of Bowie’s Pin-Ups is magnificent. Stanfield is more interested in the wider culture, with rock being as much about performance and publicity and fandom as it is about chords and melodies. Which for the writers and musicians of 1972, it almost certainly was.