A welcome corrective to the overwhelming focus on the Reed/Cale axis in just about every other volume on the band is Ignacio Juliá’s Linger On: The Velvet Underground: Legend, Truth, Interviews (Ecstatic Peace Library, 2022), an expanded edition of his Feed-Back (Munster Records, 2008), which gives centre stage to Sterling Morrison. The introductory assemblage sets the scene: Bobby Gillespie (again) on the VU as rock’s ‘best kept secret’ willed above ground and into the open by Juliá’s ‘dream power and soul energy’ that is laid alongside the author’s declaration that ‘The legend of the Velvet Underground fades away. It is no more. It's been totally exposed to the light. Their secrets have been revealed and the myth evaporated’. Carried by an occult iconography, legends, though, exist only in the process of their tale being told, otherwise we are dealing with history, and all this productivity being reviewed here suggest the legend is doing more than just sputtering on, it’s the history that is fading.

In his talks with Juliá, Morrison is lucid, thoughtful – centred. He’s not competitive, appears to have no regrets and, like Maureen Tucker, is alarmingly modest in discussing his contribution to the band. There’s a marvellous section where he recalls playing Poor Richards in Chicago while Reed was in hospital with hepatitis:

We played for a week, with all different versions of the songs, with John on vocals, and we did lots of practicing just to make the songs work. It was fun. That was the first time that anybody could go missing and the shows would go on – John or Lou or anybody, it didn’t matter. . . we moved Maureen to bass and rhythm guitar. We got Angus MacLise, the original drummer, back to play drums. So here’s this astonishing incarnation of the band. “Sister Ray” grew out of this one gig.

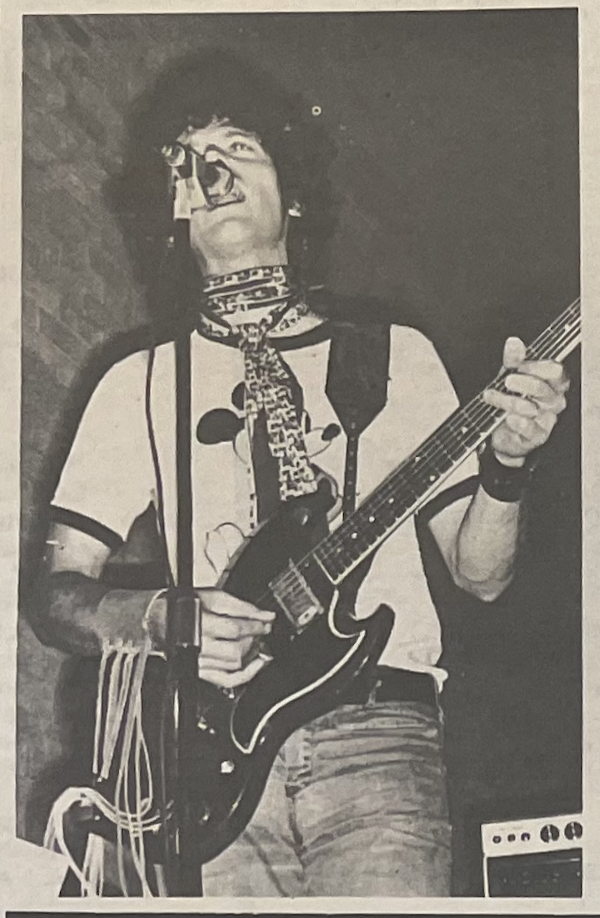

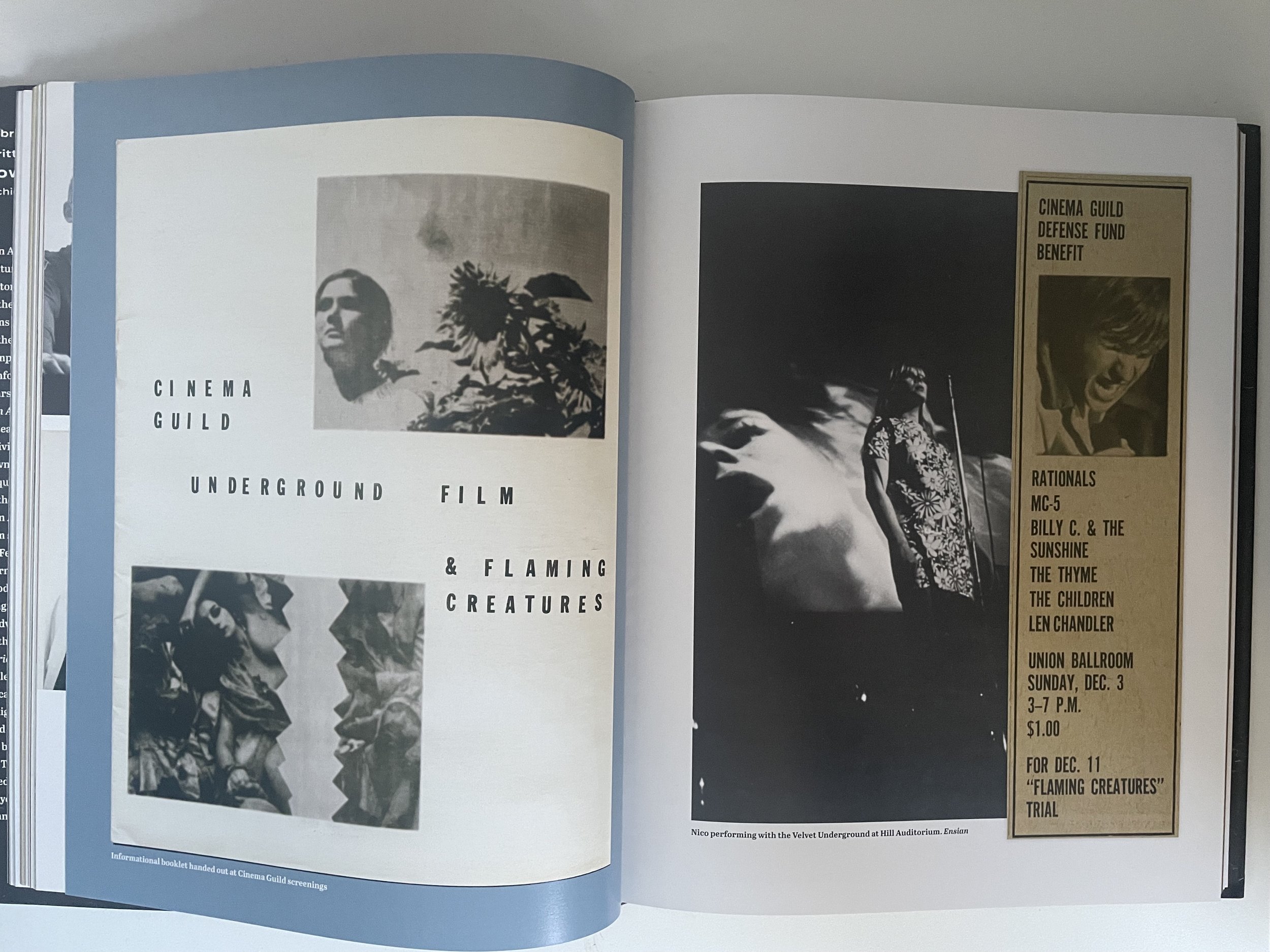

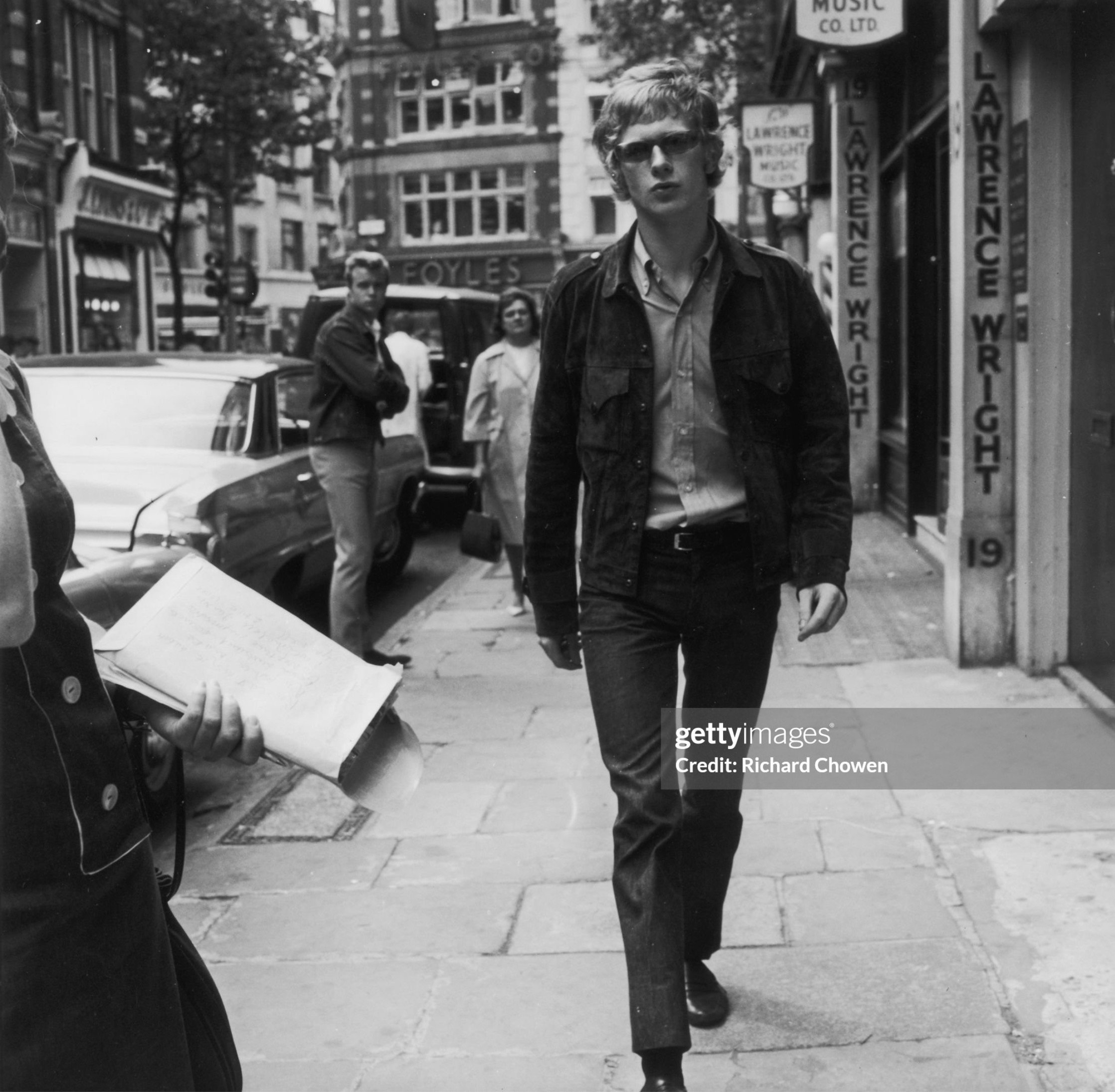

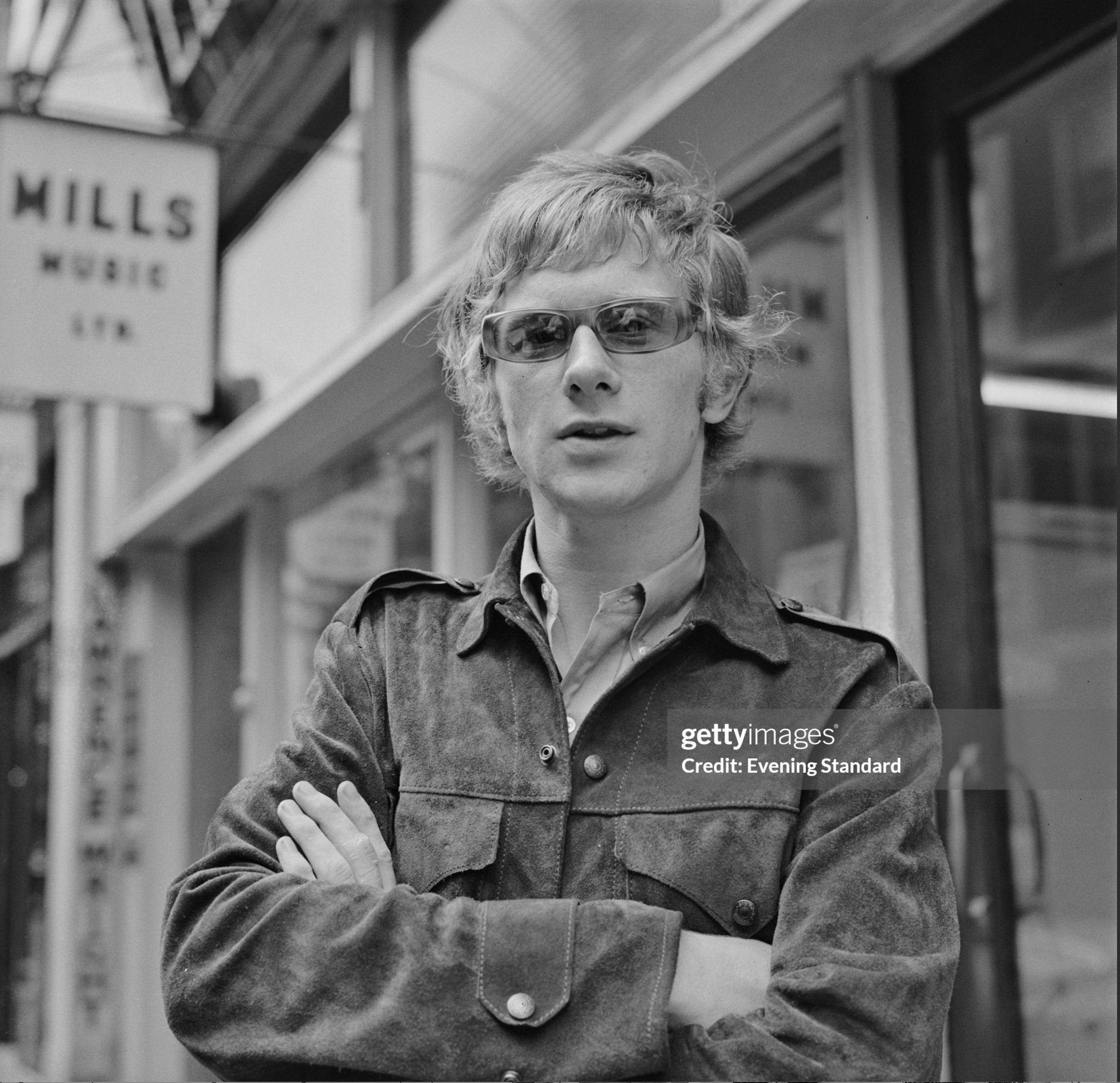

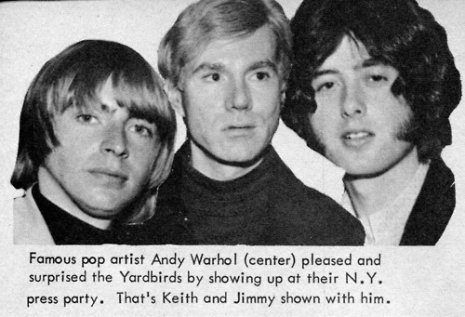

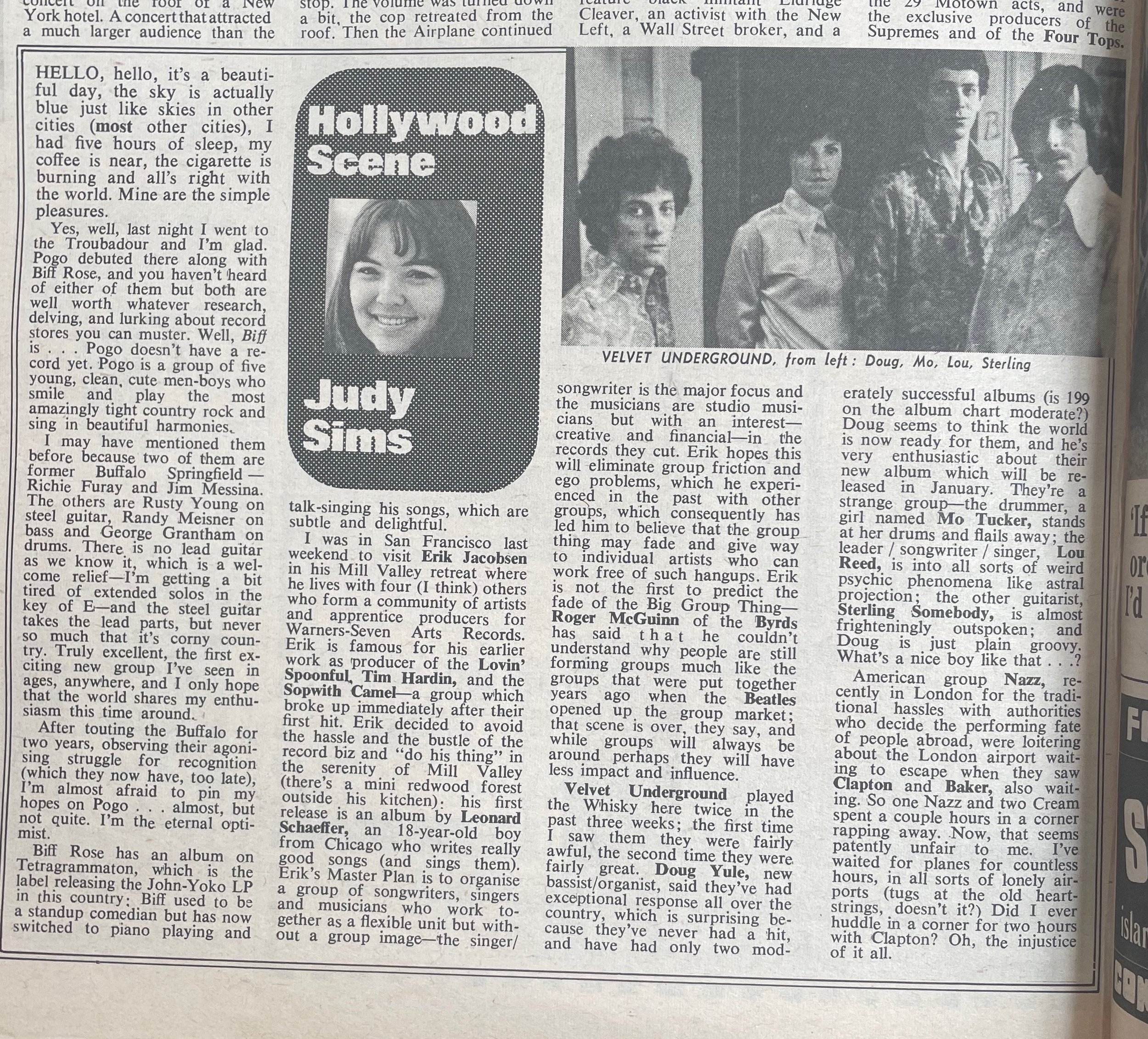

Here he is, finally in the limelight, but the spot on Morrison quickly shifts away and he is soon back on the periphery of things, stage right, looking in. In band photographs, from 1965/66, Morrison’s face is always concealed behind a mop of long hair, wraparound dark glasses, swirling cigarette smoke. Tall and skinny, cuffed Levi’s worn over black engineer boots, he was the Velvets’ suburban juvenile delinquent figure, a perfect foil for the other three but never the main event. As Juliá’s interviews mount up, with all the old Velvets – Nico, Lou, John, Moe and Doug – and with others who have stories to tell – Jackson Browne, Gerard Malanga, Lenny Kaye and Todd Haynes – as the volume of voices increases, as in Jones’ Loaded, the centre contracts. What were they all talking about? In its parts Linger On is a work to cherish, but as a whole it is a babel of competing voices all demanding equal attention.

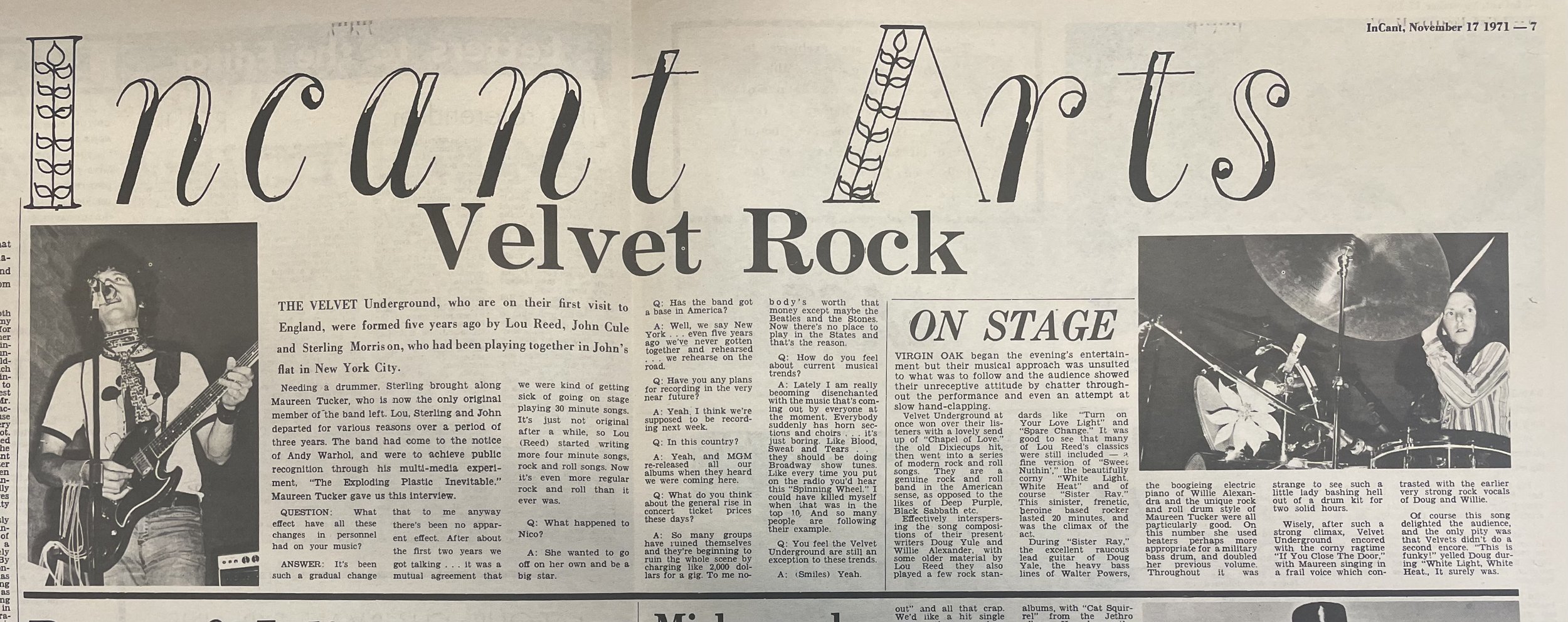

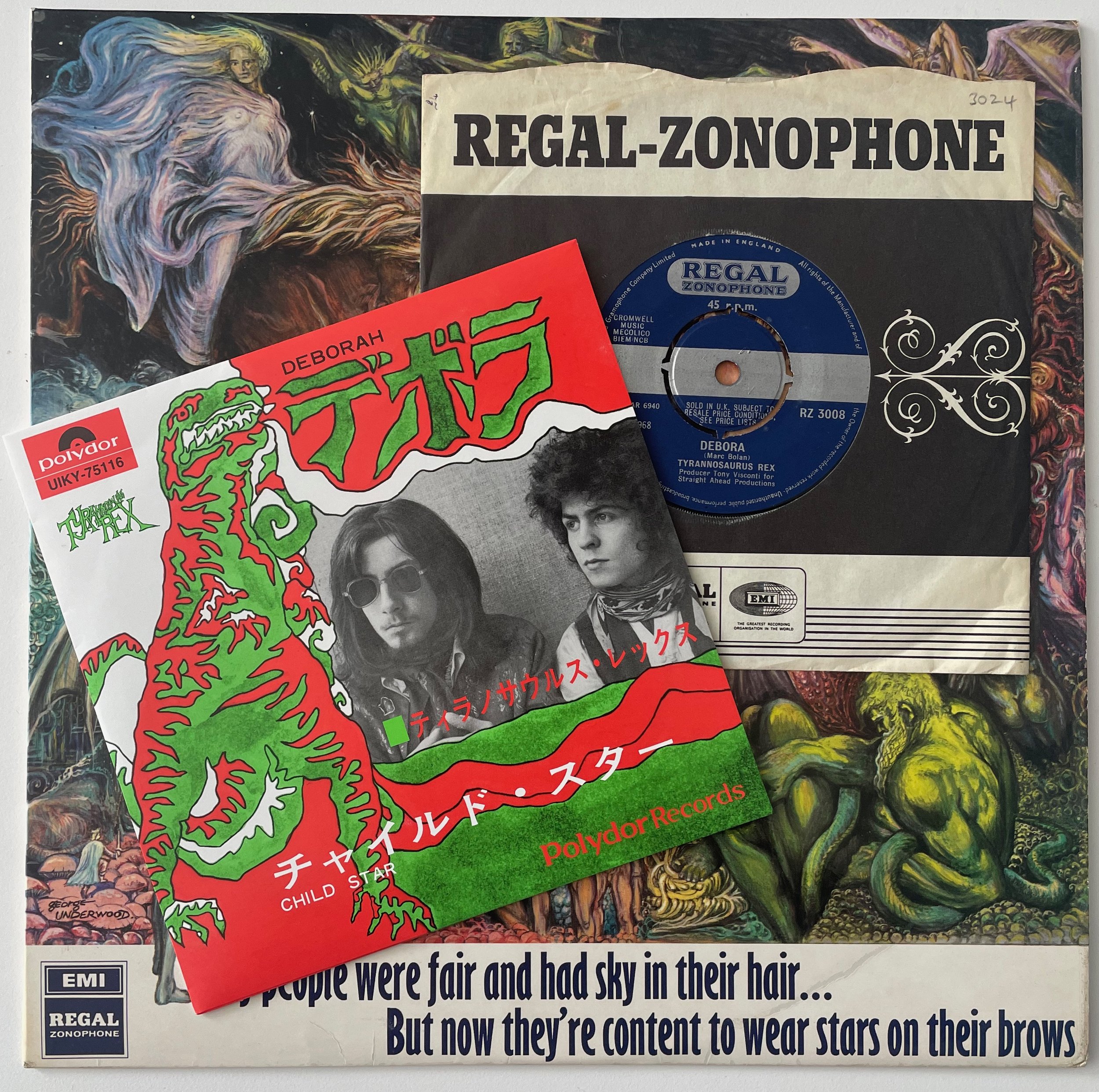

That the story’s broad outline no longer need be tendered is conspicuously the case with two lengthy articles by longstanding Velvets’ aficionado, Phil Milstein, in two recent issues of the inestimable Ugly Things. (It’s also worth noting the magazine’s publication of David Holzer’s exploration of Lou Reed’s obsession with the white light mysticism of Alice Bailey #61, Winter 2022). In #55 (Winter 2020) Milstein takes a deep dive into the world of Michael Leigh who wrote the pulp exploitation book from which The Velvet Underground took their name. The topic is, as Milstein admits, peripheral to the main event, even if the book’s cover imagery has been purloined numerous times to ground the band’s interest in the fetishistic and the taboo. Over 11 A4 sized three column pages, Milstein tracks the biography of the author and the various incarnations of his tale of the ‘bizarre sex underground’. It is an epic undertaking, excessive in its obsession and quite marvellous, even if the included photograph of Tony Conrad’s dirtied, torn and frayed personal copy – an occult relic if ever there was one – is sufficient in itself to maintain the book’s iconographic potency.